Abstract

CEOs uniquely shape activities within the firm. Among potential activities, pricing is unique: pricing has a direct and substantial effect on firm performance. In what may be the first quantitative study in industrial marketing polling exclusively CEOs globally we examine to which degree CEO championing of pricing influences pricing capabilities and firm performance. Our sample consists of 358 CEOs of industrial firms. Our results suggest that the level of championing of pricing by the CEO positively influences decision-making rationality, pricing capabilities, and collective mindfulness thereby leading to a significantly higher firm performance. This study also documents a relationship between decision making rationality and pricing capabilities (but not firm performance) thus suggesting that intuition in pricing decisions could drive firm performance.

© 2012 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Pricing is still an under-researched topic in industrial marketing: in a retrospective analysis of the content published in the Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing Dant and Lapuka (2008) find that the topic of pricing accounts for less than 5% of all articles published be- tween 1993 and 2006. Similarly, after a comprehensive review of the in- dustrial marketing literature, Reid and Plank (2000:88) conclude: “pricing continues to be an area in need of research”.

In the current study we focus on the activities of one particular individual — the Chief Executive Officer (CEO). The literature high- lights the role of organizational champions in bringing about organi- zational change (Howell & Higgins, 1990). In the current study we examine how championing activities of pricing by the CEO influence pricing capabilities and firm profitability in industrial companies. CEOs are, of course, very particular individuals: within any organiza- tion, the “levers of power are uniquely concentrated in the hands of the CEO” (Nadler & Heilpern, 1998:5). As architects of corporate strategy CEOs commit organizations to specific courses of action (Harrison & Pelletier, 1997).

Whereas earlier research suggests that the influence of the CEO on firm outcomes is rather symbolic in nature and thus limited (Pfeffer, 1981), the current literature documents a substantial CEO effect on

corporate performance, estimating that between 6% and 29% of the variance in corporate profitability is due to the CEO (Mackey, 2008). The marketing literature indicates that CEO attention positively im- pacts innovation outcomes (Yadav, Prabhu, & Chandy, 2007). CEOs thus clearly matter. Do CEO activities in pricing matter as well and, if so, through which mechanisms?

In our study we examine how CEO championing of pricing in indus- trial firms influences pricing capabilities, collective mindfulness and de- cision making rationality and how these factors influence firm profitability. CEOs themselves “will never set a single price. They can, however, give their managers the ability to win price wars, maintain price leadership and hold a competitive edge in pricing” (Dutta, Bergen, Levy, Ritson, & Zbaracki, 2002:66). CEO activities are magnified throughout the organization thus resulting in a substantial, leveraged, impact of even small activities throughout the organization (Rosen, 1990). Reports by pricing practitioners suggest that the pricing function is increasingly driven by chief executives or other members of the executive management team (Jacobson, 2007). Empirically, the lack of CEO support is an important obstacle in the implementation of value-based pricing strategies (Hinterhuber, 2008).

In our survey, we poll 358 CEOs from companies around the world by making use of the database maintained by the Young Presidents’ Organization. To the best of our knowledge this is the first study in in- dustrial marketing making use of this database. To the best of our knowledge this is also one of the very few global studies in industrial marketing polling only CEOs: Auh and Menguc (2007, 2009), for ex- ample, poll 260 Australian CEOs and senior executive, Auh and Menguc (2005) poll 242 national (likely US) CEOs, Aragon-Correa, Garcia-Morales, and Cordon-Pozo (2007) use 408 Spanish CEOs, and

Sluyts, Matthyssens, Martens, and Streukens (2011) use 235 Belgian CEOs. Other studies have a large share (60%) of CEOs among respon- dents, but also use operating managers (Land, Engelen, & Brettel, 2012). Finally, qualitative research with the CEO as main respondent is quite frequent (Keating & McLoughlin, 2010; Zerbini, Golfetto, & Gibbert, 2007).

In other words, quantitative, global surveys with the CEO as re- spondent are not very frequent in industrial marketing, but potential- ly very illuminating given the uniqueness of the position of a CEO within any organization.

Understanding the link between CEO commitment to and involve- ment in pricing and the design and performance of an organization allows us to further shed light on a specific type of strategic action – championing of the pricing function – through which CEOs can influ- ence firm performance. Our inquiry contributes to the fields of pricing and industrial marketing by linking CEO championing behaviors to three organizational factors – pricing capabilities, collective mindful- ness and decision making rationality – and subsequently to relative firm performance. Most importantly, our data highlight the role of or- ganizational champions and imply that purposeful championing of pricing by CEOs influences organizational design for pricing and firm performance. Our results also underline the role of decision mak- ing rationality in building pricing capabilities. Contrary to expecta- tions, we do not find an effect of decision making rationality on firm performance. For future research this potentially suggests that, con- versely, intuition in pricing decision could positively affect firm performance.

2. Theoretical background and hypotheses

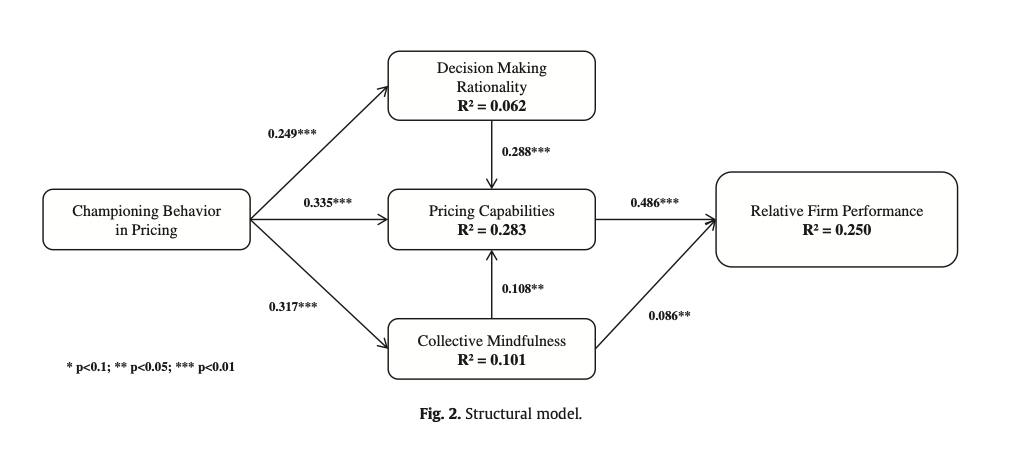

The development of our theoretical model draws from related streams of literature: industrial pricing, the resource-based view of the firm and from organization theory, particularly the literature on bounded rationality, organizational champions and collective mindful- ness. Fig. 1 below describes our hypothesized research model

2.1. Pricing literature from an organizationalperspective

Several studies examine pricing practices from the perspective of organizational decision processes but, among them, only a handful link the bodies of knowledge on pricing and organizational behaviors. Cyert and March (1992), who study pricing behaviors in a retail envi- ronment, suggest that, over time, simplifying rules of thumb emerge within the firm. They argue that prices are negotiated between vari- ous departments of the firm as a way to reach consensus and achieve negotiated objectives. Finally, they propose that cost-based pricing practices are included among these rules of thumb or routines. Lancioni, Schau, and Smith (2005) research the intraorganizational influence on business-to-business pricing strategies and more specif- ically the importance of interdepartmental rivalry and conflicting in- terests on the pricing process. The findings show that resistance to progressive pricing strategies emanates from many groups in firms each of them “having parochial interests and agendas” Lancioni et al. (2005:130). The most dominant resistance and roadblocks are created by the finance department which is ranked as the most diffi- cult to work with in developing a comprehensive pricing policy. Ingenbleek (2007) conducts a literature review of 53 pricing studies drawn from cost-theory, decision making theory and marketing strategy: Ingenbleek proposes a conceptual framework and several directions for future research in the field of value-informed pricing. His review of the literature suggests that information sources repre- sent a key resource to be acquired, developed and deployed within the firm. However, the availability of information does not guarantee success in value-informed pricing — the degree to which information is processed, interpreted, communicated and used can influence the implementation of it. Thus the pricing process within the firm can in- fluence the management of information related to customer value perceptions. Ingenbleek (2007) makes the following critical conclu- sions with regards to pricing literature: 1) it is highly descriptive and lacks statistical significance; 2) research insights on pricing prac- tices are often not cumulative; and 3) theory about how price deci- sions are made in firms is limited. We build on the scholarly work of Cyert and March, Lancioni, and Ingenbleek by bridging the fields of pricing and organizational behavior.

2.2. Organizational champions

Leaders can influence both functional management commitment and the adoption of innovative technology and practices in firms (March & Simon, 1958:219). Top management support strongly im- pacts functional management commitment. This type of top manage- ment support is needed for complex initiatives such as total cost of ownership calculations in sourcing (Wouters, Anderson, & Wynstra, 2005) or value-based pricing (Hinterhuber, 2008), which require strong inter-functional cooperation. Hinterhuber (2008), for example, finds that the lack of support from senior management is an important obstacle in the implementation of value-based pricing strategies.

Senior management support for customer-value management processes is a re- quirement when firms try to implement a “philosophy” of doing business based on demonstrated value to customers (Anderson, Kumar, & Narus, 2007:13). Senior management must “take a broader view of persuasively conveying this value merchant mind-set and culture to everyone work- ing in the business and to the customers” (Anderson et al., 2007:123). Hinterhuber (2008:49) finds that “senior management (support) can be obtained through various means, including lobbying, networking, and bargaining. If such support is gained, middle-ranking executives can then implement value-based pricing strategies”.

Top management plays a key role in defining and promoting corporate-wide priorities and new strategic programs but also in iden- tifying, allocating and deploying strategic resources to support these programs (Chandler, 1973). Executive experience, overall personality, and risk aversion behaviors help determine the course and rate of struc- tural adaptation and innovation (Chandler, 1973; Jaworski & Kohli, 1993). The influence, skills and drive of upper management are a re- source leading to better strategy and greater economic rents by firms (Barney & Clark, 2007). Leadership styles (authoritative versuspartici- pative) and backgrounds (legal, finance or marketing) also impact the organization (Chandler, 1973; Simon, 1961).

Organizational champions are charismatic, (Nadler & Tushman, 1990) transformational leaders (Bass, 1985; Wang & Huang, 2009) and advocate change (Nadler & Nadler, 1997:98). Champions may exhibit a “constellation of behaviors” (Howell, Shea, & Higgins, 2005:643) that can be nurtured and learned — including “communi- cating a clear vision of what innovation could be or do, displaying en- thusiasm and demonstrating commitment to it, and involving others in supporting it” (Howell & Higgins, 1990:323). They may increase effort-accomplishment expectancies by reinforcing collective efficacy and increase self-efficacy and collective efficacy by expressing posi- tive evaluations (Tasa, Taggar, & Seijts, 2007) and showing confidence in people to perform effectively and to meet challenges (Nadler & Tushman, 1990). Recent research finds that CEO attention acts as signif- icant catalyst for organizational outcomes (Yadav et al., 2007). Qualita- tive research highlights the critical role of the CEO to act as champion to promote the pricing function, to nurture capabilities in pricing and to ensure decision making rationality (Liozu & Hinterhuber, 2012). We thus hypothesize.

H1. CEO championing activities have a positive impact on the decision- making rationality of the firm.

H2. CEO championing activities have a positive impact on pricing capabilities.

H3. CEO championing activities have a positive impact on the collec- tive mindfulness of the firm.

2.3. Decision makingrationality

Simon (1961:93) posits that actual behavior of managers in firms when making decisions or making choices falls short of objective ra- tionality in three ways: 1) the incompleteness of knowledge; 2) the difficulties in anticipation of the consequences that will follow choice; and 3) the choice among all possible alternative behaviors. Managers also suffer from possible “bottleneck of attention” that impacts their ability to deal with more than a few things at a time (Simon, 1961:90). Bounded rationality refers to the notion that rational actors are significantly constrained by limitations of information and calcu- lations (Cyert & March, 1992:214). Behavioral theorists conjecture that managers in organizations simplify the decision-making process by using various behaviors (Cyert & March, 1992:264): satisficing (March, 1978); following rules of thumb (Schwenk, 1988); and defin- ing standard operating procedures and organizational routines

(Feldman, 2000; Pentland & Reuter, 1994). Others will define frames of reference (March & Simon, 1958:159) which will be determined “by the limitations of the rational man’s knowledge”. Experienced man- agers will draw from their memory, training and experience (Simon, 1961:134). They construct and use “cognitive heuristics” (Brownlie & Spender, 1995:42) or mental models (Porac, Thomas, & Baden-Fuller, 1989) to simplify complex strategic issues and engage in intuitive and judgmental responses to decision-demanding situations (Barnard & Andrews, 1968; Oxenfeldt, 1973). The resolution of uncertainty is “to create a rationality, a recipe or an interpretative scheme” (Brownlie & Spender, 1995:43) leading to a choice or a decision. We thus conjecture:

H4. Decision making rationality is positively related to pricing capabilities.

H6. Decision making rationality is positively related to firm performance.

2.4. Organizational mindfulness

Mindfulness is a state of alertness and active information process- ing (Langer, 1989) that includes: creating new categories rather than relying on categories present in our memory; welcoming new infor- mation by being open and attending to changed signals; and welcom- ing more than one view and being aware of multiple interpretations. Fiol and O’Connor (2003:60) observe that “the greater the level of mindfulness of decision makers, the more likely it is they will use de- cision making mechanisms to expand their search for information.” Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld (1999) extend the concept of individual mindfulness (Langer, 1989, 1997) to the collective, describing it as the widespread adoption and diffusion of mindfulness by the organization’s members. Mindfulness helps organizations to notice more issues, process them with care, and detect and respond to early signs of trouble (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2007). Weick and Sutcliffe (2007) and Weick et al. (1999) describe five cognitive processes that constitute organizational mindfulness: 1) preoccupation with failure; 2) reluctance to simplify interpretations; 3) sensitivity to op- erations; 4) commitment to resilience; and 5) deference to expertise. We contend that these characteristics of high reliability organizations can also be applied to the adoption and implementation of pricing strategies in firms.

Firms engaged in the development of modern pricing practices invest in developing pricing capabilities of their front line personnel through pricing training for sales employees in order to equip them with the tools and capabilities to achieve the firm’s pricing goals. Sensitivity to op- erations also entails adjusting pricing programs by taking into account the knowledge of people who actually do the work (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2007). Commitment to resilience is strongly influenced by executive champions’ internal development of shared beliefs, courage and resil- ience when implementing pricing strategies. Finally, firms defer pricing decision expertise and influence to center-led pricing teams. Decision makers in business units rely on the expertise of these specialized cen- ters of excellence to optimize pricing decisions and firm’s performance. Recent qualitative research explores the idea of mindfulness in pricing and suggests that it increases both firm pricing capabilities as well as firm performance (Liozu, Hinterhuber, Perelli, & Boland, 2012). We thus hypothesize:

H5. Collective mindfulness is positively related to pricing capabilities.

H8. Collective mindfulness is positively related to firm performance.

2.5. Capabilities and resource based view of thefirm

The resource-based view of the firm (Wernerfelt, 1984) sees the firm as a unique bundle of resources and capabilities where the primary task of management is to maximize value (Grant, 1996). These resources include all assets (physical and nonphysical), capa- bilities, organizational processes, firm attributes, information, knowl- edge etc. controlled by the firm that enable a firm to conceive and implement strategies that improve its efficiency and effectiveness (Barney, 1991). A specific combination of these tangible and intangi- bles resources and capabilities is valuable, rare and difficult to imitate or acquire by competitors (Barney & Clark, 2007; Dierickx & Cool, 1989; Hall, 1993) and cannot be captured on a piece of paper (Nadler & Tushman, 1990:18). A positive relationship between firm capabilities and profitability exists also in business markets (Kaleka, 2002; Merrilees, Rundle-Thiele, & Lye, 2011; Nath, Nachiappan, & Ramanathan, 2010).

Dutta, Zbaracki, and Bergen (2003) specifically highlight the role of pricing capabilities as antecedents of firm performance. In contrast to the marketing capability literature, these authors define pricing capabil- ities as set of complex routines, skills, systems, know-how, coordination mechanisms and complementary resources. Pricing capability refers to, on the one hand, the price setting capability within the firm (identifica- tion of competitor prices, setting pricing strategy, and translation from pricing strategy to price) and, conversely, to the price setting capability vis-à-vis customers (convincing customers on the price change logic, negotiating price changes with major customers). In this and subse- quent research settings, pricing capabilities are positively related to company performance (Berggren & Eek, 2007; Hallberg, 2008). In these studies, pricing capabilities are complex, difficult to imitate processes which span organizational boundaries. All of these studies use qualitative research. In other words, the link between pricing capabilities as complex routines and skills and organizational per- formance has not yet been explored in a quantitative survey. We posit:

H7. Pricing capabilities are positively related to firm performance.

3. Methods

3.1. Data collection andsampling

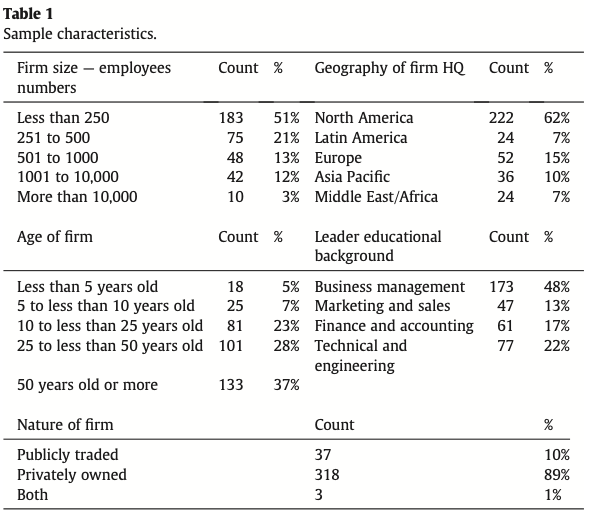

Following the total design method (Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, 2009), we send a cross-sectional self-administered electronic survey in April, 2011 to 7897 active members of the Young President Organization International. This organization is a for-profit organization with 18,000 members composed exclusively of CEOs, business owners or presidents in 110 countries. Member companies comprise B2B as well as B2C com- panies. Members must meet eligibility criteria, such as, age (under 45 years old), title (President, Chief Executive Officer, Chairman of the Board, Managing Director), enterprise value (minimum $10 million North American, privately held company with less than 250 employees. Table 1 below provides more descriptive information about our sample

3.2. Measure development andassessment

We adapt most scales from the current literature and develop a new scale to measure pricing capabilities. We refine the scale through pre- tests and pilot testing using established item development procedures and guidelines (Churchill, 1979). We determine content and face valid- ity through a comprehensive review of the literature, pre-and pilot tests, and assessment by a panel of practitioners and academics to en- sure that measurement items covered the domain of the constructs (Churchill, 1979; Nunnally, 1978). To assess the quality of the survey items, we conduct in-depth, face-to-face interviews with pricing practi- tioners using Bolton’s talk aloud methodology (Bolton, 1993). We pre- test all scale items with a small panel of academics and pricing and business practitioners.

We pilot-test the survey instrument with 150 professionals representing pricing, business and general manager functions from companies in both manufacturing and service industries and receive 70 complete responses. We iteratively modify the survey instrument to incorporate all relevant test results. None of the pretest or pilot test participants are included in the final sample. The survey instrument is presented in the Appendix

3.2.1. Behavior of champion onpricing

We adapt a six-item scale from Howell et al. (2005) to assess pricing champion behaviors (CBE). We measure each item by a seven-point Likert scale anchored at the extremes by ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree.

3.3.2. Pricingcapabilities

Since there is little empirical precedent to measure pricing capa- bilities (PC), we develop a multiple-item scale in accord with an oper- ational definition (Kerlinger & Lee, 1999), by relying on our fieldwork, and on extant literature. Our scale covers the three critical dimen- sions of pricing (Hinterhuber, 2004): the customer perspective (mea- suring and quantifying maximum willingness to pay, price elasticity, and value-in-use), the competitor perspective (knowledge about price levels of competing products, ability to respond to market changes), and the company perspective (availability of pricing tools, existence of price-management processes, availability of trainings to develop employee skills in pricing). We use twelve items ranging from 1 — ‘much worse than competitors’ to 7 — ‘much better than competitors’ to operationalize this scale.

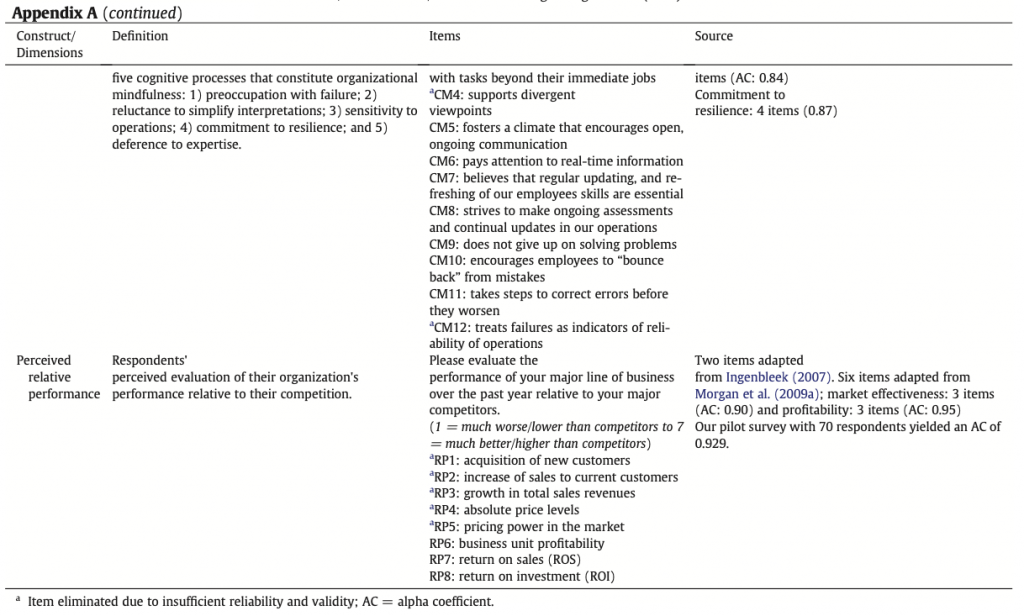

3.2.3. Collective mindfulness

The twelve item scale used to measure collective mindfulness (CM) is based on adapting existing measures (Knight, 2004) and con- ceptual definitions in the literature (Dane, 2011; Weick & Sutcliffe, 2007): collective mindfulness refers to the ability of individuals with- in organization to notice a large variety of issues (wide attention breadth), to process these issues with care (high present moment ori- entation) and to detect and respond to early warning signals. Conse- quentially, we assess sensitivity to operations (4 items), reluctance to simplify (4 items), and commitment to resilience (4 items) using seven-point, Likert-type scales.

3.2.4. Decision making rationality

We adapt a 4 item scale developed by Miller (1987) and relate the construct – measuring concepts of analysis, future orientation and planning, explicitness of the strategy, and systematic scanning of the environment – to pricing decisions. The seven-point scale is an- chored with ‘does frequently’ at the extreme positive end and ‘does rarely’ at the opposite end of the scale.

3.2.5. Firm performance

Similar to Morgan, Vorhies and Morgan (2005), we operationalize firm performance as a second-order construct consisting of three first-order reflective constructs — sales, pricing and profit perfor- mance. The measures for sales and profit are adapted from Morgan, Vorhies, and Mason (2009) and include six items, while the other two measures are from the work of Ingenbleek (2007). The use of subjective performance measures is required for a number of reasons. First, because our sample contained many privately owned firms for which objective accounting data on their performance are not acces- sible, we follow the convention (Simsek, 2007; Simsek, Veiga, Lubatkin, & Dino, 2005) of asking CEOs to compare their firms’ relative performance to that of their competitors on eight different dimensions for the past year (e.g. growth in sales, return on investment, return on sales and so forth) using a scale ranging from 1 (‘much worse’) to 7 (‘much better’) than competitors (Song, Droge, Hanvanich, & Calantone, 2005). Researchers express strong reservations about the use of objective performance data specifically in research settings in- volving small and medium-sized companies, since these data are bi- ased as a result of managerial manipulation for corporate and personal tax reasons (Sapienza, Smith, & Gannon, 1988). Second, since firms in our sample are of various types and from various geo- graphical zones, a multidimensional measure based on perceptual firm performance facilitates comparisons across firms and contexts, such as across industries, time horizons, and economic conditions. Fi- nally, earlier studies show that perceptual performance measures tend to be highly correlated with objective indicators (Dess & Robinson, 1984): more recently Kumar, Jones, Venkatesan, and Leone (2011) find a high correlation (0,8) between subjective and ob- jective data on firm performance. Subjective performance data are used widely in strategy research (Anderson & Paine, 1975). Taken in the aggregate, subjective or perceptual measures of firm performance can provide a broad indication of a company’s health (Quinn, Baily, Herbert, Meltzer, & Willett, 1994).

3.2.6. Firm-level control variables

We control for a number of likely determinants of performance by including demographic characteristics of the firm, such as firm type, age, and firm size (Amburgey & Rao, 1996).

3.3. Non-response bias

A commonly used method for estimating the bias in strategy re- search (for examples see Armstrong & Overton, 1977) is to compare early — those who responded within the first week (74%) and late (26%) responses among the study variables; a late respondent is con- sidered a proxy for a non-respondent. One way ANOVA tests, performed at the item level indicate no significant differences in data derived from early vs. late responders, except on 1 of the 26 (1.73%) study variables. Consequently, it appears that bias present from the time of response is due to chance.

3.4. Common method bias

Surveys from a single set of respondents can introduce common method bias (CMB) in the data. Consequently, we take several steps to mitigate, detect, and control for a common method bias. We care- fully construct all survey items, and wherever possible, used pre- tested, valid, multidimensional constructs (Huber & Power, 1985). We vary the scale anchors and format in the questionnaire, perform a series of scale-validation processes before distributions, and ran- domize questions.

Several post hoc tests determine the extent to which common meth- od bias is present in our data. First, using Harman’s single-factor test, all 26 items are entered into an unrotated principal components factor analysis to determine the number of factors necessary to account for the variance in the variables. Accordingly, if a single factor emerges or a single general factor explains most of the variance between the inde- pendent and dependent variables, common method variance may be present (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). Our results in- dicate the presence of six potential factors (all with eigenvalues greater than one), each factor explained roughly equal variance, and explained over 53% of the total variance. These results provide initial evidence re- sponse bias does not appear to be a problem in the data (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986).

Second, an unrelated construct, a marker variable, determined ex post to have no signification correlation with other items in the constructs is added to the measurement model (Lindell & Whitney, 2001). Since we do not measure an unrelated construct a priori, we use a modified test in which a weakly related construct – CEO perceptions of pricing – a four-item scale is used (Pavlou & Gefen, 2005). High correlations among any of the items of the study’s constructs and pricing percep- tion indicate common method bias. Since the highest correlation of pricing perceptions and the constructs is r = 0.15, there appears to be minimal evidence of common method bias.

Third, we examine multicollinearity and CMB with linear regres- sion analysis on the study constructs and find low variance inflation factors. Further, multicollinearity can be ruled out because no two predictor variables correlated more strongly than 0.70 (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010). Finally, we examine the correlation matrix, as shown in Table 3, and find no highly correlated factors (highest correlation is r = 0.566), whereas evidence of common method bias S.M. Liozu, A. Hinterhuber / Industrial Marketing Management 42 (2013) 633–643 637 will result in high correlations (r > 0.90). Based on these tests, multicollinearity is not present and common method bias does not appear to pose a problem with our analysis.

3.5. Measurement models

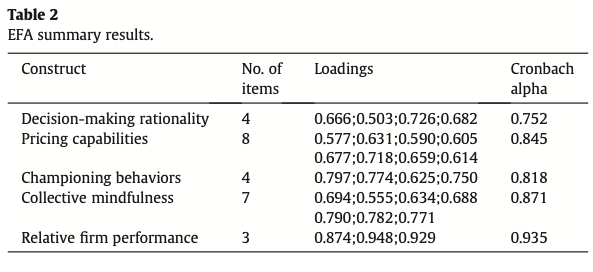

We conduct an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) on the sample dataset to determine whether each of the items, particularly those for the new scales, reliably measured its intended construct. Factor analysis results confirm the existence of five factors, with each item loading on its respective factor in support of unidimensionality (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). The items generally load well on the factors, but on 4 out of the 26 items factor loadings are below 0.6 (Table 2).

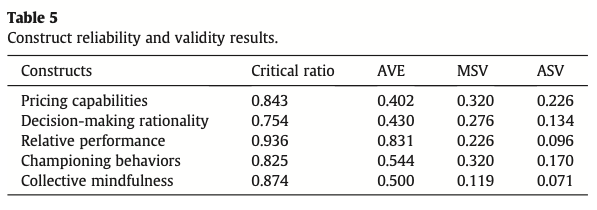

We assess the psychometric properties of the six factors derived from the EFA using a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to validate the factor structure. Without exception, the composite reliability (CR) for each construct exceeds the commonly used norm for accept- able psychometrics (>0.70). As shown in Table 5, AVE exceeds the average squared variance (ASV) and maximum squared variance (MSV) in all cases providing further evidence of discriminant validity.

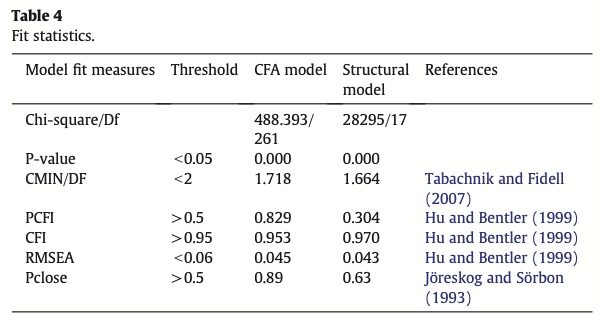

The overall fit for the model meets the conventional standards and is considered acceptable as represented by χ2/d.f.=1.718, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA]=0.045, normed fit index [NFI]=0.932, nonnormed fit index [NNFI]=0.895, incremental fit index [IFI]=0.953, and comparative fit index [CFI]=0.953 (Table 4).

3.6. Invariance test

To establish the model is not significantly affected by the region in which the organization operates, we conduct configural and metric invariance tests (Steenkamp & Baumgartner, 1998) to the measure- ment model. Due to the unequal sampling from different regions, we are constrained to split the data into two groups: North America (n = 222) and Other (n = 136), rather than five groups (for each of the five regions); sample sizes in the non-North American regions are too small to support measurement model estimation using a five-group model. Using the two-group model, we observe adequate fit for the unconstrained measurement models (cmin/df=1.589; CFI = 0.925; RMSEA = 0.041). After constraining the models to be equal, we find the chi-square difference test to be non-significant (pval>0.05). Thus our measurement model meets criteria for metric and configural invariance across regions.

4. Results

We test our hypotheses using structural equation modeling (SEM). SEM is particularly appropriate because it allows estimation of multiple associations, simultaneously incorporates observed and latent constructs in these associations, and accounts for the biasing effects of random measurement error in the latent constructs (Medsker, Williams, & Holahan, 1994).

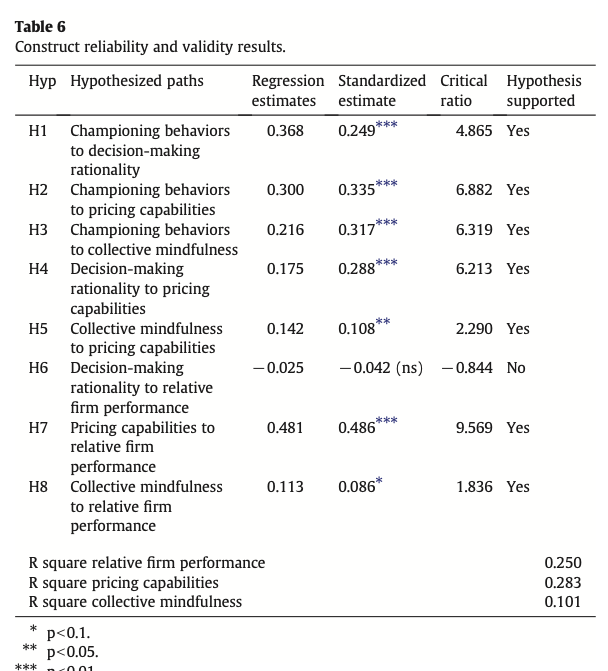

The results are in Table 6. All hypothesized relationships are signifi- cant, except for H6 (Firms’ decision making rationality will be related pos- itively to relative firm performance). The fit indices (Table 4) for the final structural model shown in Fig. 2 indicate that this model reaches an ac- ceptable level for goodness of fit (χ2(2)=28.295; p=0.000, χ2/df= 1.664, CFI=0.970, IFI=0.972; NNFI=0.932 and RMSEA=0.043).

First, championing behaviors have a positive and significant im- pact on pricing capabilities (0.335, p b 0.01), on collective mindfulness (0.317, pb0.01), and on decision making rationality (0.249, pb0.01). These findings support H1, H2 and H3. Second, collective mindfulness is both positively and significantly related to the firms’ pricing capa- bilities (0.108, p b 0.05) and firm performance (0.086, p b 0.1), thereby validating H5 and H8. Third, decision making rationality is significant- ly and positively related to pricing capabilities (0.288, pb0.01) pro- viding support for H4. Decision making rationality (−0.035) has no effect on firm performance, thus H6 is not supported. Finally, pricing capabilities have a positive and significant impact on firm perfor- mance (0.486, p b 0.01), thereby supporting H7.

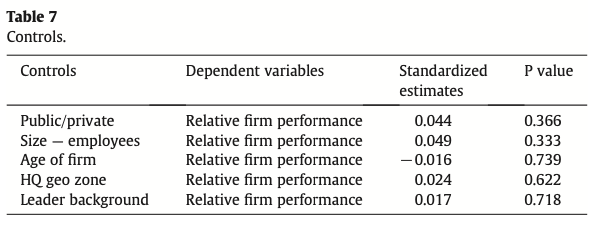

We control for company type (public/private, age and size of the firm, geographical zones and leader’s main education background. We control for firm size as in previous studies (Morgan et al., 2009) and firm age. No significant effects on performance emerge (Table 7).

5. Discussion

Strategy is “the pattern of activities determinant of the gain in a context of market exchange” (Snehota, 1990:164). In this study we examine the impact of one particular type of strategic activity – CEO championing activities of pricing – on firm performance. We focus on pricing activities since pricing is a frequently overlooked area in industrial marketing (Lancioni, 2005).

Lancioni et al. (2005) identify senior management as the organiza- tional layer presenting the largest number of obstacles to price setting and price planning in industrial firms. This study, conversely, takes a complementary perspective in examining to which extent (active) CEO championing behaviors influence pricing capabilities and firm profitability in industrial companies. Our findings offer four substan- tive contributions.

First, our results support the proposition that a purposeful championing of pricing activities by top executives strongly influ- ences the organizational design to support the pricing process: CEO championing positively and significantly influences pricing capabili- ties, decision-making rationality, and collective mindfulness. By pro- viding evidence of these relationships, we uniquely begin the exploration of organizational drivers of the pricing function. Our con- clusions suggest that, once top executives realize the importance of pricing and purposefully decide to champion it, the impact on the organization and its performance is significant.

In line with previous stud- ies (Mackey, 2008) we find that CEOs clearly matter and provide support for studies in business markets on the role of senior management in de- signing and implementing pricing strategies (Lancioni et al., 2005).

Second, our results support resource-based theory that pricing capa- bilities positively and significantly influence firm performance vis-à-vis competition. Previous studies on marketing capabilities suggest a positive link between pricing capabilities – a subset of marketing capabilities – and firm performance (Morgan et al., 2009; Vorhies & Morgan, 2005). However, these studies measure pricing capabilities as part of a much wider subset of marketing capabilities using a narrow, 3-item scale: We develop a new 12-item scale for pricing capabilities to reflect the complex processes and organizational routines which pricing capabilities encom- pass (Dutta et al., 2003). Our findings show that pricing capabilities are significantly influenced by championing behaviors, decision-making ra- tionality, mindfulness and overall pricing orientation. In turn, these capa- bilities in pricing positively influence firm performance vis-à-vis competition in industrial companies.

Third, our findings suggest that the CEO is essential for the successful implementation of pricing in industrial firms. Pricing should become a top priority for CEOs. By investing to build pricing capabilities that gen- erate a sustainable and inimitable competitive advantage, champions of pricing forge shared vision, a collective can-do mentality and a sense of resilience in the firm that lead to superior levels of organizational effica- cy (Bohn, 2001) and superior outcome. Dutta et al. (2002:66) state that “most CEOs will never set a single price. They can, however, give their managers the ability to win price wars, maintain price leadership and hold a competitive edge in pricing.”

Finally, this study finds a positive relationship between decision mak- ing rationality and pricing capabilities, but – contrary to expectations – does not find a relationship between decision making rationality and firm performance. Decision making rationality thus contributes to the development of pricing capabilities within firms, but not to firm performance.

The absence of a relationship between decision making rationality and firm performance points, at least in principle, towards the role of in- tuition. The role of intuition in decision-making theory is gaining interest as of recent (Sadler-Smith & Shefy, 2004).

Intuitive decision making is increasingly viewed as a viable and acceptable approach in today’s business context (Burke & Miller, 1999). Intuition may be an ap- propriate decision-making process in certain situations and business scenarios, especially in situations of uncertainty, turbulence (Khatri & Ng, 2000), or novelty. Scholars relate the intuitive skills of managers to the intuitive skills of chess masters or physicians (Simon, 1987). Ex- perienced managers have in memory a large amount of experience, schemas and patterns gained through experience and organized “in terms of recognizable chunks and associated information” (Simon, 1987:61). Managers need to be able to combine both approaches to reach a greater level of decision effectiveness (Dane & Pratt, 2007; Simon, 1987). Intuition can then become a complement to an appropri- ate pricing decision after a thorough analytical and scientific process. An interesting avenue for future research is thus the exploration of contin- gencies which favor decision making rationality versus intuition in in- dustrial pricing. An exploration of the consequences of intuitive decision making in industrial pricing is warranted.

6. Limitations

The use of a large sample of CEOs from countries across the globe as sole respondents is a novelty in industrial marketing. This study has, however, four important limitations which offer fruitful avenues for fu- ture research. First: causality. Our quantitative survey confirms two key relationships: the relationship between CEO championing and pricing capabilities and the relationship between pricing capabilities and firm performance. We base these hypothesized relationships on substantial empirical research which suggests that championing influences capa- bilities (Nadler & Tushman, 1990; Tasa et al., 2007) and that capabilities influence performance (Barney, 1991; Dutta et al., 2003). Qualitative re- search in industrial pricing provides further support for these two rela- tionships (Liozu & Hinterhuber, 2012). Nevertheless, this survey is cross sectional and we cannot rule out reverse causality. Our agreement with the Young Presidents’ Organization, the members of which we survey,

prevents us from re-polling respondents to collect data on, for example, prior performance which could be used to mitigate reverse causality concerns. The guarantee on confidentiality which we have given to po- tential respondents to solicit participation prevents us from attempting to link individual CEO responses to information on financial perfor- mance obtained, for example, from annual reports or from information brokers. A very important avenue for future research is thus the explo- ration of the relationship between CEO championing activities, firm ca- pabilities and firm performance through longitudinal research. Second: the response rate. The response rate of our survey of 358 CEOs is 12% and low compared to typical response rates in industrial marketing, but fairly consistent with the response rate of CEO surveys (Hambrick et al., 1993; Simsek et al., 2010). This comparatively low response rate may limit the ability to generalize results. Third: common method bias. We collect data from one individual per organization — the CEO. Data from multiple respondents should be used in future studies to re- duce common method bias (Burton-Jones, 2009). Finally: factor load- ings: the items generally load well on the factors, but on 4 out of the 26 items we measure factor loadings are below 0.6.

Directions for future research include: longitudinal studies on the effect of championing behaviors by chief executives on pricing capa- bilities and firm performance; studies exploring the effect of intuition in (pricing) decisions on firm performance; finally, studies exploring the antecedents of pricing capabilities in industrial firms.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Editor as well as two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments which have contributed substantial- ly towards improving the paper.

References

Amburgey, T. L., & Rao, H. (1996). Organizational ecology: Past, present, and future directions. Academy of Management Journal, 39(5), 1265–1286.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411.

Anderson, J. C., Kumar, N., & Narus, J. A. (2007). Value merchants: Demonstrating and documenting superior value in business markets. Harvard Business School Press. Anderson, C. R., & Paine, F. T. (1975). Managerial perceptions and strategic behavior.

The Academy of Management Journal, 18(4), 811–823.

Aragon-Correa, J. A., Garcia-Morales, V. J., & Cordon-Pozo, E. (2007). Leadership and organizational learning’s role on innovation and performance: Lessons from Spain. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(3), 349–359.

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys.

Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396–402.

Auh, S., & Menguc, B. (2005). Top management team diversity and innovativeness: The

moderating role of interfunctional coordination. Industrial Marketing Management,

34(3), 249–261.

Auh, S., & Menguc, B. (2007). Performance implications of the direct and moderating

effects of centralization and formalization on customer orientation. Industrial

Marketing Management, 36(8), 1022–1034.

Auh, S., & Menguc, B. (2009). Broadening the scope of the resource-based view in marketing:

The contingency role of institutional factors. Industrial Marketing Management, 38(7),

757–768.

Barnard, C., & Andrews, K. (1968). The functions of the executive. Harvard University Press. Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of

Management, 17(1), 99.

Barney, J., & Clark, D. (2007). Resource-based theory: Creating and sustaining competitive

advantage. USA: Oxford University Press.

Bass, B. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press. Berggren, K., & Eek, M. (2007). The emerging pricing capability. School of Economics and

Management, Lund University.

Bohn, J. (2001). The design and validation of an instrument to assess organizational efficacy.

Unpublished dissertation, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee.

Bolton, R. N. (1993). Pretesting questionnaires: Content analyses of respondents’

concurrent verbal protocols. Marketing Science, 12(3), 280–303.

Brownlie, D., & Spender, J. (1995). Managerial judgement in strategic marketing.

Management Decision, 33(6), 39–50.

Burke, L. A., & Miller, M. K. (1999). Taking the mystery out of intuitive decision making.

The Academy of Management Executive, 13(4), 91–99 (1993–2005).

Burton-Jones, A. (2009). Minimizing method bias through programmatic research. MIS

Quarterly, 33(3), 445–471.

Chandler, A. (1973). Strategy and structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Churchill, G. A. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing

constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73.

Cyert, R., & March, J. (1992). A behavioral theory of the firm. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. Dane, E. (2011). Paying attention to mindfulness and its effects on task performance in

the workplace. Journal of Management, 37(4), 997–1018.

Dane, E., & Pratt, M. G. (2007). Exploring intuition and its role in managerial decision

making. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 33.

Dant, R. P., & Lapuka, I. I. (2008). The journal of business-to-business marketing comes

of age: Some postscripts. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 15(2), 192–197. Dess, G. G., & Robinson, R. B., Jr. (1984). Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures: The case of the privately held firm and conglomer-

ate business unit. Strategic Management Journal, 5(3), 265–273.

Dierickx, I., & Cool, K. (1989). Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competi-

tive advantage. Management Science, 35(12), 1504–1511.

Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2009). Internet, mail, and mixed-mode

surveys: The tailored design method (3rd ed.). Wiley.

Dutta, S., Bergen, M. E., Levy, D., Ritson, M., & Zbaracki, M. (2002). Pricing as a strategic

capability. MIT Sloan Management Review, 43(3), 61–66.

Dutta, S., Zbaracki, M. J., & Bergen, M. (2003). Pricing process as a capability: A

resource-based perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 24(7), 615–630. Feldman, M. (2000). Organizational routines as a source of continuous change. Organization

Science, 11(6), 611–629.

Fiol, C., & O’Connor, E. (2003). Waking up! Mindfulness in the face of bandwagons. The

Academy of Management Review, 28(1), 54–70.

Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management

Journal, 17, 109–122.

Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis

(7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hall, R. (1993). A framework linking intangible resources and capabilities to sustainable competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 14(8), 607–618. Hallberg, N. (2008). Pricing capabilities and its strategic dimensions. School of Economics and Management, Lund University.

Hambrick, D. C., Geletkanycz, M. A., & Fredrickson, J. W. (1993). Top executive commitment to the status quo: Some tests of its determinants. Strategic Management Journal, 14(6), 401–418.

Harrison, E. F., & Pelletier, M. A. (1997). CEO perceptions of strategic leadership. Journal of Managerial Issues, 9, 299–317.

Hinterhuber, A. (2004). Towards value-based pricing — An integrative framework for decision making. Industrial Marketing Management, 33(8), 765–778.

Hinterhuber, A. (2008). Customer value-based pricing strategies: Why companies resist.

Journal of Business Strategy, 29(4), 41–50.

Howell, J., & Higgins, C. (1990). Champions of technological innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(2), 317–341.

Howell, J., Shea, C., & Higgins, C. (2005). Champions of product innovations: Defining, developing, and validating a measure of champion behavior.

Journal of Business Venturing, 20(5), 641–661.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Huber, G. P., & Power, D. J. (1985). Retrospective reports of strategic level managers: Guidelines for increasing their accuracy. Strategic Management Journal, 6(2), 171–180.

Ingenbleek, P. (2007). Value-informed pricing in its organizational context: Literature review, conceptual framework, and directions for future research. The Journal of Product and Brand Management, 16(7), 441–458.

Jacobson, T. (2007). Global pricing transformations: The emotional, political, and ratio- nal aspects of getting to results. 18th Annual Fall Conference of the Professional Pricing Society, Orlando, FL.

Jaworski, B., & Kohli, A. (1993). Market orientation: Antecedents and consequences. The Journal of Marketing, 57(3), 53–70.

Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbon, D. (1993). LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International Inc.

Kaleka, A. (2002). Resources and capabilities driving competitive advantage in export markets: Guidelines for industrial exporters. Industrial Marketing Management, 31(3), 273–283.

Keating, A., & McLoughlin, D. (2010). The entrepreneurial imagination and the impact of context on the development of a new venture. Industrial Marketing Management, 39(6), 996–1009.

Kerlinger, F. N., & Lee, H. B. (1999). Foundations of behavioral research (4th ed.).

Wadsworth Publishing.

Khatri, N., & Ng, H. A. (2000). The role of intuition in strategic decision making. Human Relations, 53(1), 57.

Knight, A. (2004). Measuring collective mindfulness and exploring its nomological network. Unpublished dissertation, University of Maryland, College park, MD. Kumar, V., Jones, E., Venkatesan, R., & Leone, R. P. (2011). Is market orientation a source of sustainable competitive advantage or simply the cost of competing? Journal of Marketing, 75(1), 16–30.

Lancioni, R. (2005). Pricing issues in industrial marketing. Industrial Marketing Management, 34(2), 111–114.

Lancioni, R., Schau, H. J., & Smith, M. F. (2005). Intraorganizational influences on business-to-business pricing strategies: A political economy perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 34(2), 123–131.

Land, S., Engelen, A., & Brettel, M. (2012). Top management’s social capital and learning in new product development and its interaction with external uncertainties. Industrial Marketing Management, 41(3), 521–530.

Langer, E. (1989). Mindfulness. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Langer, E. (1997). The power of mindful learning. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114.

Liozu, S., Boland, R., Hinterhuber, A., & Perelli, S. (2011). Industrial pricing orientation: The organizational transformation to value-based pricing. 1st International Conference on Engaged Management Scholarship, 2011 [Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract= 1839838 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1839838]

Liozu, S., & Hinterhuber, A. (2012). Industrial product pricing: A value-based approach.

Journal of Business Strategy, 33(4), 28–39.

Liozu, S., Hinterhuber, A., Perelli, S., & Boland, R. (2012). Mindful pricing: Transforming

organizations through value-based pricing. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 20(3), 197–209.

Mackey, A. (2008). The effect of CEOs on firm performance. Strategic Management Journal,

29(12), 1357–1367.

March, J. (1978). Bounded rationality, ambiguity, and the engineering of choice. Bell

Journal of Economics, 9(2), 587–608.

March, J., & Simon, H. (1958). Organizations. John Wiley & Sons.

Medsker, G. J., Williams, L. J., & Holahan, P. J. (1994). A review of current practices for evaluating causal models in organizational behavior and human resources management research. Journal of Management, 20(2), 439–464

Merrilees, B., Rundle-Thiele, S., & Lye, A. (2011). Marketing capabilities: Antecedents

and implications for B2B SME performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(3), 368–375.

Miller, D. (1987). Strategy making and structure: Analysis and implications for performance.

The Academy of Management Journal, 30(1), 7–32.

Morgan, N. A., Vorhies, D. W., & Mason, C. H. (2009). Market orientation, marketing

capabilities, and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 30(8), 909–920.

Nadler, D. A., & Heilpern, J. D. (1998). The CEO in the context of discontinuous change.

In D. Hambrick, D. A. Nadler, & M. Tushman (Eds.), Navigating change: how CEOs, top teams, and boards steer transformation (pp. 3–27). Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Nadler, D., & Nadler, M. B. (1997). Champions of change: How CEOs and their companies are mastering the skills of radical change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Nadler, D. A., & Tushman, M. L. (1990). Beyond the charismatic leader and organiza- tional change. California Management Review, 32(2), 77–97.

Nath, P., Nachiappan, S., & Ramanathan, R. (2010). The impact of marketing capability, op- erations capability and diversification strategy on performance: A resource-based view. Industrial Marketing Management, 39(2), 317–329.

Nunnally, J. (1978). Fundamentals of factor analysis. In J. C. Nunnally (Ed.), Psychometric theory (pp. 327–404). (2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Oxenfeldt, A. (1973). A decision-making structure for price decisions. The Journal of Marketing, 37(1), 48–53.

Pavlou, P. A., & Gefen, D. (2005). Psychological contract violation in online marketplaces: An- tecedents, consequences, and moderating role. Information Systems Research, 16(4), 372. Pentland, B., & Reuter, H. (1994). Organizational routines as grammars of action.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(3), 484–510.

Pfeffer, J. (1981). Management as symbolic action: The creation and maintenance of organizational paradigms. Research in Organizational Behavior, 3(1), 1–52.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. -Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Prob- lems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531.

Porac, J. F., Thomas, H., & Baden-Fuller, C. (1989). Competitive groups as cognitive com- munities: The case of Scottish knitwear manufacturers. Journal of Management Studies, 26(4), 397–416.

Quinn, J. B., Baily, M. N., Herbert, G. R., Meltzer, R. C., & Willett, D. (1994). Information technology: Increasing productivity in services [and executive commentary]. The Academy of Management Executive, 8(3), 28–51 (1993–2005).

Reid, D. A., & Plank, R. E. (2000). Business marketing comes of age: A comprehen- sive review of the literature. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 7(2–3), 9–186.

Rosen, S. (1990). Contracts and the market for executives. (NBER) Working Paper No. 3542 National Bureau of Economic Research [http://www.nber.org/papers/w3542] Sadler-Smith, E., & Shefy, E. (2004). The intuitive executive: Understanding and apply- ing ‘gut feel’ in decision-making. The Academy of Management Executive, 18(4), 76–91 (1993–2005).

Sapienza, H. J., Smith, K. G., & Gannon, M. J. (1988). Using subjective evaluations of organizational performance in small business research. American Journal of Small Business, 12(3), 45–53.

Schwenk, C. R. (1988). The cognitive perspective on strategic decision making. Journal of Management Studies, 25(1), 41–55.

Simon, H. A. (1961). Administrative behavior. New York: Macmillan.

Simon, H. A. (1987). Making management decisions: The role of intuition and emotion.

The Academy of Management Executive, 1(1), 57–64 (1987–1989).

Simsek, Z. (2007). CEO tenure and organizational performance: An intervening model.

Strategic Management Journal, 28(6), 653–662.

Simsek, Z., Heavey, C., & Veiga, J. J. F. (2010). The impact of CEO core self evaluation on the firm’s entrepreneurial orientation. Strategic Management Journal, 31(1), 110–119. Simsek, Z., Veiga, J. F., Lubatkin, M. H., & Dino, R. N. (2005). Modeling the multilevel de- terminants of top management team behavioral integration. The Academy of

Management Journal, 48(1), 69–84.

Sluyts, K., Matthyssens, P., Martens, R., & Streukens, S. (2011). Building capabilities to manage strategic alliances. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(6), 875–886. Snehota, I. (1990). Notes on a theory of business enterprise. Doctoral thesis, Uppsala University.

Song, M., Droge, C., Hanvanich, S., & Calantone, R. (2005). Marketing and technology resource complementarity: An analysis of their interaction effect in two environ-mental contexts. Strategic Management Journal, 26(3), 259–276.

Steenkamp, J. B. E. M., & Baumgartner, H. (1998). Assessing measurement invariance in cross-national consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(1), 78–107. Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Multivariate analysis of variance and covariance. Using multivariate statistics (pp. 243–310). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Tasa, K., Taggar, S., & Seijts, G. (2007). The development of collective efficacy in teams: A multilevel and longitudinal perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 17–27.

Vorhies, D., & Morgan, N. (2005). Benchmarking marketing capabilities for sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Marketing, 69(1), 80–94.

Wang, Y. S., & Huang, T. C. (2009). The relationship of transformational leadership with group cohesiveness and emotional intelligence. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 37(3), 379–392.

Weick, K., & Sutcliffe, K. (2007). Managing the unexpected: Resilient performance in an age of uncertainty. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Weick, K. E., Sutcliffe, K., & Obstfeld, D. (1999). Organizing for high reliability: Process- es of collective mindfulness. Research in Organizational Behavior, 21, 81–123.

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180.

Wouters, M., Anderson, J., & Wynstra, F. (2005). The adoption of total cost of ownership for sourcing decisions — A structural equations analysis. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 30(2), 167–191.

Yadav, M. S., Prabhu, J. C., & Chandy, R. K. (2007). Managing the future: CEO attention and innovation outcomes. Journal of Marketing, 71(4), 84–101.

Zerbini, F., Golfetto, F., & Gibbert, M. (2007). Marketing of competence: Exploring the resource-based content of value-for-customers through a case study analysis. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(6), 784–798.

Stephan M. Liozu is President and CEO of ARDEX Americas, a high performance building materials company based in Pittsburgh, PA. He is also a Ph.D. in Management candidate (2013) at Case Western Reserve University, Weatherhead School of Management. His re- search interest focuses on pricing and value management from an organizational and be- havioral perspective.

Over the past three years, Mr. Liozu published academic articles in MIT Sloan Management Review, the Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, Journal of Business Strategy as well as in the Journal of Strategic Marketing. Mr. Liozu has also written several articles on stra- tegic pricing issues for the Journal of Professional Pricing and is a regular presenter at Pro- fessional Pricing Society conferences in Europe and North America as well as the Strategic Account Management Association conferences. Together with Andreas Hinterhuber he is a co-editor of the book Innovation in Pricing — Contemporary Theories and Best Practices (Routledge, 2012).

Andreas Hinterhuber is a Partner of Hinterhuber & Partners (www.hinterhuber.com), a consultancy company specialized in strategy, pricing, and leadership. He is also a visiting professor at USI Lugano, Switzerland and was acting chair and head of the Department of International Management at Katholische Universität Eichstätt-Ingolstadt (Germany). Previously he has been working for ten years in global management positions in the chemical and pharmaceutical industry. He has published articles in Industrial Marketing Management, Long Range Planning, MIT Sloan Management Review, Journal of Strategic Marketing, and other journals. Together with Stephan Liozu he is a co-editor of the book Innovation in Pricing — Contemporary Theories and Best Practices (Routledge, 2012).