Abstract Few companies treat innovation in pricing as seriously as product innova- tion or business model innovation. However, after interviews with 50 executives and the analysis of pricing practices of 70 companies worldwide, our research suggests that innovation in pricing may be a company’s most powerful–—and, in many cases, least explored–—source of competitive advantage. Innovation in pricing brings new-to- the-industry approaches to pricing strategies, to pricing tactics, and to the organiza- tion of pricing with the objective of increasing customer satisfaction and company profits; too many companies today see pricing as a win/lose proposition between themselves and their customers. Innovation in pricing breaks this deadlock and shows how to increase profits and customer satisfaction conjointly. As a result of our research, we present a canvas laying out more than 20 possible avenues for innovation in pricing, offering to any organization–—regardless of size, industry, or nationality–— a few key ideas on how to increase both profits and customer satisfaction.

Ⓒ 2014 Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Is product innovation a top priority for your com- pany? If so, you are certainly not alone. Has your firm tinkered with business-model innovation? Great. Your competitors have done this already and cus- tomers may even expect it. But what about another advancement that is less recognized, yet still a crucial factor in product innovation: Could innova- tion in pricing be your next source of competitive advantage? Based on a series of interviews with CEOs and top management personnel–—as well as analysis regarding pricing practices at leading companies in the U.S., Europe, and Asia (see Appendix)–—we es- timate that less than 5% of companies have applied innovation to their pricing strategy, tactics, or or- ganization. Our research shows that companies that implement innovation to their pricing activ- ities significantly outperform their competitors.

* Corresponding author

E-mail addresses: andreas@hinterhuber.com (A. Hinterhuber), sliozu@case.edu (S.M. Liozu)

0007-6813/$ — see front matter Ⓒ 2014 Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2014.01.002

Thus, chances are good that innovation in pricing is your next and most powerful source of competitive advantage.

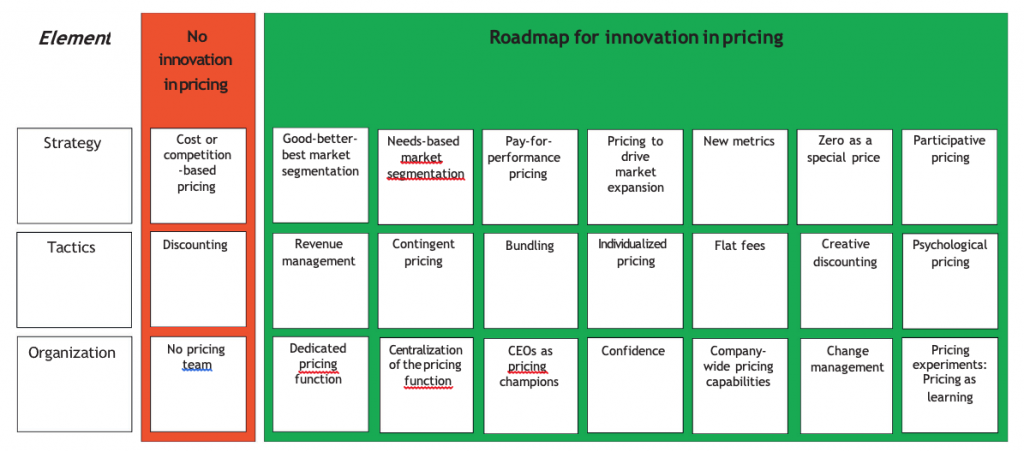

Based on our research, we develop a framework to kick-start innovation in pricing. This roadmap provides a unique overview for understanding cur- rent global best practices of innovation in pricing and for guiding organizations to successfully imple- ment it. The roadmap, which lays out more than 20 possible avenues for innovation in pricing, offers organizations–—regardless of size, industry, or na- tionality–—a few key ideas on innovation in pricing. Our research suggests that this is enough: many highly successful companies (e.g., Zipcar, Salesfor- ce.com) have built their competitive advantage essentially around one, and only one, pricing inno- vation.

In this article, we first define innovation in pricing and discuss why it is too often neglected. Then we develop our roadmap for action. Following that, we delve into the essence of the framework by showing how the use of innovation in pricing strategy, tac- tics, and organization can lead to superior profits and increased customer satisfaction.

2. What is innovation in pricing?

Most companies unfortunately view pricing as an- tagonistic: a win-lose relationship with customers in that what one party gains the other loses, or so goes the weakly held assumption. Our research shows that innovation in pricing helps to break this vicious cycle. Such innovation brings new-to-the-industry approaches to pricing strategies, to pricing tactics, and to the organization of pricing with the objective of increasing customer satisfaction and company profits. As we illustrate via examples proffered, the joint increase of company profitability and cus- tomer satisfaction constitutes the hallmark of in- novation in pricing.

The experience of General Electric (GE) high- lights the importance of innovation in pricing. Historically, the company sold aircraft engines to airlines at or below cost in an attempt to recover profits through intransparent maintenance con- tracts. Customer satisfaction was low: service con- tracts were expensive and capital outlays were high. GE struggled to bridge the gap between its own capital outlays and cash inflows. Innovation in pricing enables the company to overcome both problems. Instead of selling jet engines, GE now sells what it calls ‘‘Power by the Hour’’; that is, usage rights to jet engines, which include main- tenance and spare parts. Customers pay only when the aircraft is flying, and thus earn money. In

contrast to maintenance contracts, GE now has every incentive to ensure that the jet engines perform. As a result, profits–—as well as customer satisfaction–—increase dramatically. In a similar vein, the success of companies such as Salesfor- ce.com and Zipcar is not based on product inno- vation but rather rests solidly on innovative approaches to pricing. Instead of selling software, Salesforce.com licenses usage rights to customers who appreciate the advantage of tying payments to usage intensity. Contrast this with traditional soft- ware pricing whereby customers pay a fixed fee regardless of the benefits experienced. Similarly, Zipcar’s success in the car rental industry is not due to better vehicles or improved customer service but lies predominantly with the company’s pricing schemes, which give customers the option to pay for rental cars on a much more flexible basis: by the minute.

Innovation in pricing is thus already a source of competitive advantage for a small number of lead- ing companies. It is less about numbers and much more about the appropriate model that will enable a company to grow profitably while at the same time provide superior customer satisfaction. If innovation in pricing is such a powerful tool to drive profitability, why are so few companies embracing it?

3. Why innovation in pricing is not a priority

Our research suggests that product or service in- novation is a top-management priority for close to 100% of companies. But only 5% of companies in- troduce new-to-the-industry pricing innovations; only one company from our interviews has imple- mented an innovative pricing strategy. Like GE, this business-to-business (B2B) equipment company has shifted from selling products to charging customers a given fee that reflects the enhanced productivity realized and includes service, maintenance, and performance guarantees. This new approach pro- pels the company from an also-ran to an industry leader in terms of customer satisfaction, growth, and profitability.

As interesting as this single case may be, it is an exception. The typical answer we received from companies surveyed was ‘‘No, we have not intro- duced any innovation in pricing.’’ Many executives who are true pioneers in fields such as product innovation, marketing, finance, and talent develop- ment seem to hold the following weakly held con- viction: ‘‘Pricing did not change that much over the past decades, so why should it change now?’’ This

conviction may have been nurtured in part by the fact that, with the exception of a few pioneering studies (e.g., Hewitt & Patterson, 1961; Hinterhuber & Liozu, 2013; Nagle, 1983), academic research in this area is still scarce.

We contend that it is a mistake to underrate the position of pricing as an enabler of innovation. Powerful advances in information technology as well as emerging dynamics in customer behavior are dramatically changing what is possible in pricing. Our research suggests that the following roadmap can provide a strong framework to guide innovation in pricing.

4. Roadmap for innovation in pricing

Our framework (Figure 1) starts with a simple premise: about 95% id companies do not engage systematically in pricing innovation. For these companies, pricing strategy is largely based on competition or cost – based pricing, and pricing tactics are limited to discounting. Furthermore, these organisations do not have a dedicated function: for example, a chief pricing officer responsible for improving price setting or price – getting capabilities. The essence of the framework is three key areas that our research suggests are critical in approaching any pricing inovation: strategy, tactics, and organization. This framework should by used as a canvas for executives to facilitate the plotting of their current pricing practices. More importantly, by mapping out the universe of best-practice innovations in pricing, this canvas encourages executives to consider alternative approaches to pricing. Next, we break down the essential elements of the framework and look at innovation in pricing strategy, tactics and organisation.

4.1. Innovation in pricing strategy

4.1.1. Good-better-best market segmentation One way to implement innovation in pricing strategy is to move from a one-size-fits-all pricing policy to a policy with multiple price and value configurations reflecting differences in value creation for different market segments. Good-better-best market seg- mentation offers individuals a large number of prod- ucts at different price points in order to address a broad array of customers with large variations in willingness to pay. Allstate, one of the most profit- able auto insurance companies, is able to success- fully compete against no-frills Internet competitors through a policy of price and value segmentation. Depending on the client’s brand/price sensitivity and need for customer support, Allstate divides individuals into four distinct clusters (high/low brand sensitivity and high/low self-service) and competes in these different market segments through four distinct brands, offering a substantially different customer experience at different price points.

4.1.2. Needs-based market segmentation Although good-better-best market segmentation is an innovation for many companies, this approach has an important limitation: customers typically struggle to understand to which degree these different products meet their needs. In other words, customers have very specific and complex needs, not just the desire to purchase a low-price,mid-price, or premium price product. Recent aca- demic research suggests that needs-based is the current gold standard in market segmentation (Best, 2012; Kotler & Keller, 2011). Practitioners agree. Hans Strasberg, CEO of Swedish household appliance manufacturer Electrolux, says (Knudsen, 2006, p. 76):

Figure 1. A roadmap for innovation in pricing

Given the differences in what customers value, we have abandoned the traditional industry segmentation based on price and a ‘good better best’ hierarchy. Now our segmentation has as many as 20 product positions that relate di- rectly to different lifestyle and purchasing pat- terns of consumers.

Needs-based market segmentation allows the company to simultaneously offer a multitude of products in the premium as well as the entry-level category with close to zero cannibalisation, since these products are squarely target at clearly distinct needs of well- defined customers. Since the global rollout od its needs-based market segmentation approach. Electrolux has far outpaced its competitors in terms of growth and profitability.

4.1.3. Pay-for-performance pricing

Under pay-for-performance pricing, the seller is paid depending on performance outcomes deter- mined conjointly with the customer. Consider the following example: The UK, Sweden, Australia, and Canada are among the few places where reimburse- ment of new pharmaceutical products is closely tied to criteria reflecting the new product’s incremental value over existing therapies. For new pharmaceut- icals, the UK has a threshold range of £20,000 to

£30,000 per QUALY (quality-adjusted life year). In this environment, Velcade (bortezomib), by Johnson & Johnson–—a product for treating multiple myelo- ma–—is considered not cost effective since treat- ment costs are approximately £3,200 per treatment cycle, or £40,000 per QUALY. Traditional pricing approaches thus would have suggested either to drop the price to reach the threshold, implying a price drop by up to 50%, or to exit the UK market. Johnson & Johnson, however, proposed an alterna- tive pricing approach to regulatory authorities. Under the new pricing scheme, the pharmaceutical company links reimbursement to effectiveness. On- ly when patients respond fully to the new drug do they remain on therapy; in this scenario, the drug is funded by the National Health System. When pa- tients show no or minimal response, the treatments cease and Johnson & Johnson bears the full cost. This new approach–—full reimbursement in case of no response–—reduces the costs for patients on therapy to approximately £22,000 per QUALY. Asa result, Velcade is today the market share leader in the UK while also being the most expensive therapy in this segment. Advertising, industrial services (e.g., software, consulting, logistics, transportation), and complex engineering projects are other areas in which pay- for-performance pricing is currently widespread. Performance-based pricing is costly, largely because monitoring is intensive. Nevertheless, we expect to see a substantial increase in these arrangements in other areas in the future, especially as regards consumer-goods markets.

4.1.4. Pricing to drive market expansion

Rather than drive competition for market share, innovative pricing approaches expand the overall market. The pricing of Ford’s Model T provides an example. In the years between 1910 and 1925, Ford reduced prices by approximately 80%, thus expand- ing sales volume more than 50-fold. In his autobiog- raphy, Henry Ford (1922, p. 146) states:

Our policy is to reduce the price, extend the operations, and improve the article. You will notice that the reduction of price comes first. We have never considered any costs as fixed. Therefore we first reduce the price to a point where we believe more sales will result. Then we go ahead and try to make the price. We do not bother about the costs. The new price forces the costs down. The more usual way is to take the costs and then determine the price, and although that method may be scientific in the narrow sense, it is not scientific in the broad sense, because what earthly use is it to know the cost if it tells you that you cannot manu- facture at a price at which the article can be sold? But more to the point is the fact that, although one may calculate what a cost is, and of course all of our costs are carefully calcu- lated, no one knows what a cost ought to be.

In a similar vein, IKEA does not allow costs to dictate prices; rather, it determines prices based on what key customer segments are willing to pay. The company then works backward to determine allow- able costs. This focus on prices as drivers of costs allows IKEA to continuously expand the overall mar- ket for home furniture.

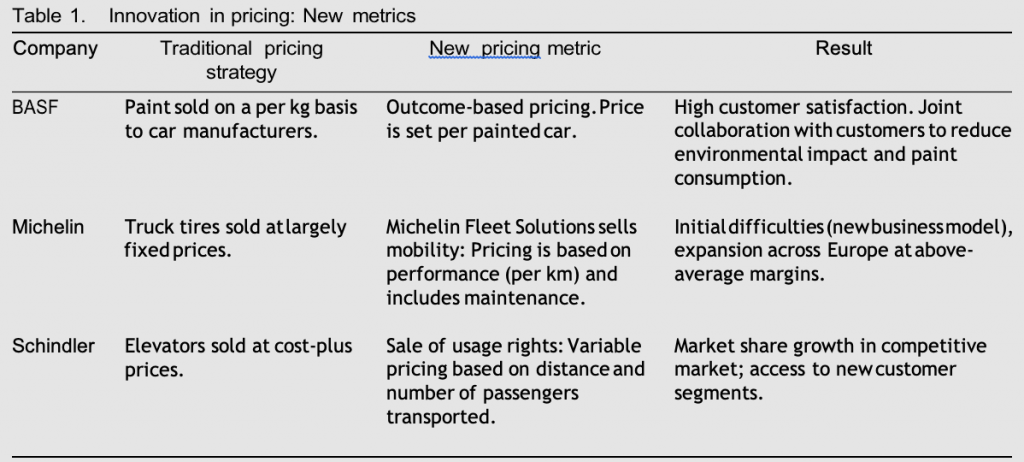

4.1.5. New metrics

Innovative pricing strategies align pricing with cus- tomer goals. This frequently leads to new pricing metrics. Theodore Levitt (1986, p. 128), a market- ing professor at Harvard Business School, famously quoted Leo McGinneva about why people buy quar- ter-inch drill bits: ‘‘They don’t want quarter-inch bits. They want quarter-inch holes.’’ Table 1 shows how some companies implement innovative pricing metrics. In all these cases, companies align the basis of their own pricing policies with clearly defined customer outcomes. This interest alignment enables high customer satisfaction, thus overcoming cus- tomer resistance to a change in pricing approach.

4.1.6 Zero as a special price

Zero is a special price, uniquely capturing customer attention (Shampanier, Mazar, & Ariely, 2007). A number of companies seem to have mastered the art of profitable growth while essentially giving away the main product. Ryanair, with average flight revenues of just s40 per customer, barely breaks even on its flight operations. Yet it is Europe’s most profitable airline, largely as a result of the profit- ability of its ancillary revenues: income from third parties, early boarding fees, baggage fees, and on- board sales. Skype (Internet calls are free, fixed-line calls are sold at regular prices), Google (search is free, advertisement is sold), fast-consumption newspapers (given away for free, advertisement is sold), and open-source software (standard models are free, customized versions are sold) compete very successfully by using similar pricing strategies.

4.1.7. Participative pricing

Recent advances in information technology enable the customer to take an active role in pricing. Participative pricing comes in two forms: name- your-own-price and pay-what-you-want. Name- your-own-price (NYOP) mechanisms ask customers to submit a bid price for a product. The customer receives the product only if this bid price is higher than an unknown threshold price. Priceline, of course, is a prime example in this respect. NYOP enables a large degree of price discrimination among customers. It is more profitable than fixed prices if the seller is a monopolist; additionally, with competition, NYOP increases profitability by allow- ing a company to expand its current customer base with price-sensitive customers who would otherwise not purchase (Shapiro, 2011). NYOP also contributes toward mitigating competition, since customers dif- fer in their bidding costs. Thus, NYOP firms target customers with low bidding costs while fixed-price sellers target customers with high bidding costs (Fay, 2009). Based on these considerations, we ex- pect that NYOP mechanisms will gain in popularity, especially in industrial markets.

Pay-what-you-want (PWYW) allows the customer full discretion in price setting. In contrast to NYOP mechanisms, sellers have to accept any price, in- cluding zero. Examples of PWYW pricing can be found in information services (e.g., Wikipedia), in museums (voluntary contributions), in the music industry (e.g., Radiohead), and the hotel and res- taurant industry. Fairness considerations, social norms, and credible threats by the seller to switch back to fixed prices (Mak, Zwick, & Rao, 2010) seem to motivate customers to pay non-zero prices. In three experimental studies involving restaurants and cinemas, PWYW pricing led to lower average prices than previously posted fixed prices but higher revenues due to new demand. Thus, participative pricing can be beneficial for sellers as well as for customers (Kim, Natter, & Spann, 2009).

4.2 Innovation in pricing tactics

4.2.1. Revenue management

Revenue management is probably the most impor- tant tactical pricing innovation in service industries: successful implementation increases company rev- enues by 3% to 7% and profits by 30% to 50% (Skugge, 2004). Revenue management varies price levels and bookable capacities conjointly to optimize profit- ability. This tactic has evolved from the travel in- dustry (airlines, then hotels, then rental cars, finally cruise lines), to leisure services (golf courses, sport clubs, restaurants), to industrial services (freight transportation, advertising time), to–—finally–—con- sumer services (equipment rental, home repair). It can be applied in industries characterized by the following features: fluctuating demand, existence of different customer segments, fixed and perish- able capacity, high fixed costs, low variable costs, and predictable demand. We anticipate that in the future, capital-intensive industrial manufacturers will consider applying revenue management to at least part of their supply. As a testimony, Infineon, a leading chip manufacturer, is currently experiment- ing with dynamic pricing (Ehm, 2010).

4.2.2. Contingent pricing

As an alternative to a fixed high- or low-price strat- egy, contingent pricing is an arrangement to sell a product at a low price if the seller does not succeed in obtaining a higher price offer during a specified period (Biyalogorsky & Gerstner, 2004). As an exam- ple, Caterpillar sells its spare parts to dealers with the option to repurchase the item at a 10% price premium in case another dealer or customer runs out of stock and has an urgent need for the product in question (Sheffi, 2005).

4.2.3. Bundling

Bundling–—that is, selling two or more products or services as a package–—increases profits since it allows companies to appropriate a larger share of customer surplus if customers differ in their relative valuation of single components. Vacation packages, car accessories, software, and subscriptions (e.g., Internet and print editions) are prime examples of bundling. Here also, innovative pricing tactics allow an increase in both customer satisfaction and firm profits.

4.2.4. Individualized pricing

Information technology enables service companies (e.g., insurers) to charge substantially different prices for identical products or services based on individual customer data. SunTrust, one of the larg- est U.S. banks, is implementing individualized pric- ing for car loans and home mortgages: the company uses software to search for instances where it under- charged customers willing to pay more for a home mortgage and also detects cases where the com- pany lost business due to excessively high prices. The software then produces an optimized, individ- ualized price for different customers (Kadet, 2008).

4.2.5. Flat fees

Flat fees are gaining popularity. Telephone compa- nies, train companies, health clubs, amusement parks, restaurants, Internet retailers (e.g., Ama- zon’s free shipping Prime program), and even exec- utive airline companies (e.g., California-based Surf Air) allow customers unlimited consumption for a fixed fee. Academic researchers document that customer preference for flat fees is typically not motivated by purely economic interests. Customers usually end up paying more with a flat fee than with a conventional pay-per-use plan, yet their satisfac- tion is higher. Customers thus pay more and are nevertheless happier.

4.2.6. Creative discounting

Robust processes for defining and monitoring dis- counting practices are a prerequisite to drive profit- ability via pricing. Even if these processes are in place, aggressive customers or aggressive compet- itors can exercise pressure on sales personnel to relax these rules and grant price concessions. Our research shows that leading-edge companies apply creativity to their discounting practices rather than slash prices across the board. Examples include:

- Non-linear pricing, whereby prices develop non- linearly with product volume. This tactic can be found in air travel (special offers where spouses pay less than full price in business class), banking services (monthly account fees drop with the number of products attained by account holders), and in all instances where paid-for membership cards (e.g., Costco) entail purchases at dis- counted prices.

- Steadilydecreasingdiscounts(Tsiros & Hardesty, 2010), whereby discounts are gradually phased out (e.g., in week 1 by 40%, in week 2 by 30%, in week 3 by 20%) as opposed to an immediate reduction in discounts under hi-lo pricing. Current research shows that steadily decreasing dis- counts lead to higher future price expectations of customers (prices increase over time as dis- counts are gradually phased out), which in turn leads to greater quantities purchased in the current period.

- Bonus packs, whereby volume can be used to imply savings. Customers mistakenly seem to as- sociate a price reduction corresponding to the amount of bonus offered. Current academic re- search (Chen, Marmorstein, Tsiros, & Rao, 2012) demonstrates the following counterintuitive find- ing: although customers should be indifferent between a 33% price reduction and a 50% bonus pack (both lead to the same per unit price), customers prefer the bonus pack, even in circum- stances where the bonus pack leads to higher average prices than the discount (e.g., 35% bonus pack versus 30% discount). Customers thus asso- ciate higher numbers (e.g., 35% free product) with greater savings, although actual prices paid are higher.

- Discount presentation, whereby perceived sav- ings can be heightened by the presentation for- mat. Common sense would suggest that presenting an offer as ‘‘pay only 60%’’ is equal to ‘‘get 40% off the regular price.’’ Recent aca- demic research (Kim & Kramer, 2006) suggests otherwise: the former discount presentation for- mat results in higher perceived savings and higher purchase likelihood than the latter. The novelty and uniqueness of the discount presentation for- mat appears as more persuasive to customers than traditional and known presentation formats.

- Cross-marketdiscounts, whereby companies lev- erage their strong position in one area to increase sales in an unrelated market. When companies are active in more than one market, they can use discounts in one market to incite sales in the other market. Giant Eagle, a dominant retailer in Pitts- burgh, also owns GetGo, a chain of gasoline sta- tions. In 2008, Giant Eagle founded its highly popular Fuelperks! campaign, via which custom- ers earn a 10-cent discount on each gallon of fuel with a $50 grocery purchase. Fuelperks! has been tremendously successful, so much that Giant Ea- gle’s competitors filed (and lost) a lawsuit claim- ing unfair sales practices. Recent empirical research (Goi´c, Jerath, & Srinivasan, 2011) shows that these cross-market discounts increase both firm profits and customer welfare, as consumers pay lower prices.

- Participativediscounts, whereby specific actions on the part of customers prompt reduced prices. Such actions include referrals and minimum pur- chase requirements. Recent research suggests that minimum purchase requirements can lead customers to feel happier when paying more (Yoon & Vargas, 2010): customers who qualify for the minimum purchase requirement (e.g.,U.S. $500) and are offered a lower discount (e.g., 20%) end up being happier than customers who are offered a larger discount (e.g., 30%) without the minimum purchase requirement.

Here, higher customer satisfaction and higher profits coexist as a result of creativity in discount- ing.

- Creativefree, whereby discounts are ‘earned’ via creative actions. Instead of fully charging for supplementary services (which customers could perceive as greedy) or giving them away for free (which hurts profits), leading companies apply creativity to select free supplementary services. For instance, Hilton Hotels in California allows free parking at its hotel facilities for all guests, under one circumstance: it applies to electric vehicles only. In this way, the company actually improves its ability to charge for parking. In addition, through this policy, customers perceive Hilton as environmentally friendly–—even if they have to pay for parking.

4.2.7. Psychological pricing

Customer preferences in business-to-consumer (B2C) and B2B markets are not stable; rather, they are constructed. Research examining psychological aspects of pricing seeks to understand how custom- ers form perceptions of value and how companies can favorably influence this. Here are some exam- ples of psychological pricing. Advertisedreference prices(e.g., manufacturer-suggested retail price $299, now only $99) influence customer behavior, even if customers themselves know that these refer- ence prices are inflated (Suter & Burton, 1996). A judicious use of advertised reference prices can thus influence customer choice toward higher margin products. In this respect, master salesman Steve Jobs provides an illuminating example. Prior to the launch of the iPad in 2010, the non-trivial question was: How on earth will Apple convince its customers to pay approximately double the price of competing tablets and still leave Apple stores with the feeling of having obtained a bargain? Enter Steve Jobs. At the iPad launch event, Jobs (2010) announced: ‘‘If you listen to the pundits, we’re going to price [the product] under $1,000, which is code for $999.’’ Behind him, $999 appeared on the video screen. He continued: ‘‘And just as we were able to meet and exceed our technical goals, we have met our cost goals. . . . I am thrilled to an- nounce to you that the iPad pricing starts not at $999, but at just $499.’’ The figure $499 replaced $999 on the screen and the audience roared.

9 endings have both level and image effects (Stiving & Winer, 1997). More than 50% of posted retail prices end in the number 9. Customers per- ceive prices ending in 9 as lower than they actually are; they also associate 9 endings with special of- fers. Despite their widespread use and possible wearoff effects, 9 endings still seem to lead to higher sales (Anderson & Simester, 2003). The com- promise effect is a phenomenon whereby brands gain market share when they become intermediate, rather than extreme, options in a choice set. Cus- tomers are averse to extreme options. Pricing man- agers thus have the option to increase the likelihood that customers buy a premium product by adding a super-premium product to their product lines. It is well documented that companies such as Starbucks, Dell, FedEx, and Amazon make heavy use of com- promise effects to profitably influence customer choice.

4.3. Innovation in pricing for the organization

Few companies are organized for pricing. Less than an estimated 5% of all companies have a dedicated pricing team responsible for analyzing, developing, and monitoring pricing capabilities. Innovation in organizing the pricing function is thus predominantly concerned with establishing novel approaches to increase the effectiveness of pricing itself. Following are potential starting points.

4.3.1. Dedicated pricing function

At its most basic level, for close to 95% of compa- nies, pricing innovation requires the establishment of a dedicated pricing function. Typical responsibil- ities include establishing a price list that reflects customer value; establishing a performance- oriented discount policy; developing guidelines to communicate value and price to customers; gather- ing information on customers, products, and sales personnel to analyze key performance indicators related to pricing (e.g., price deviations from target prices, discounting behavior by sales personnel, actual profitability versus target at customer level); developing pricing tools; assessing and developing the capability of sales personnel; and chairing the pricing council.

4.3.2. Centralization of the pricing function

Recent research suggests that a center-led pricing design, which combines elements of centralization with elements of decentralization, increases firm performance (Liozu, Hinterhuber, Perelli, & Boland, 2012). A center-led pricing organization centralizes pricing process design to a headquarter function. This central pricing function (e.g., the Chief Pricing Officer) also develops list prices, pricing tools, and key performance indicators related to pricing. Mar- keting, sales, and pricing managers in countries and business units (i.e., those in decentralized func- tions) deal with day-to-day pricing and can, with justification, deviate from centrally developed pric- ing guidelines.

4.3.3. CEOs as pricing champions

Current academic research strongly suggests that active CEO championing of pricing positively and significantly influences pricing capabilities and firm performance (Liozu & Hinterhuber, 2013a). CEO championing of pricing poses high demands on CEOs. They need to recognize the importance of pricing; enthusiastically support the pricing function and provide resources, including personal and top-man- agement attention, to the pricing team; show te- nacity when faced with obstacles to necessary price changes; identify key actors responsible for solving pricing problems when they arise; and, finally, pub- licly show confidence in what pricing can do for customer satisfaction and company profitability.

4.3.4. Confidence

Confidence may be the single most important in- tangible differentiator between high-performing and low-performing companies with respect to pric- ing (Hinterhuber & Liozu, 2012). Innovation in pric- ing requires confidence: the belief in one’s own abilities to take on any challenge, a sense of pur- pose, a vision for and confidence in the future, the conviction that one’s products/services deliver val- ue, the courage to implement price changes in the market, and–—finally–—the ability to say no to cus- tomer requests for price reductions. Our research suggests that imbuing sales personnel with confi- dence is a leadership responsibility: high-perform- ing companies have CEOs who instill confidence in their sales teams by encouraging them to set high standards for excellence, enabling them to build an emotional reservoir gained through valuable expe- riences, and encouraging them to trust their own judgment.

4.3.5 Company-wide pricing capabilities

Pricing capabilities are a complex bundle of routines that cover the three critical dimensions of pricing: the customer perspective (measuring and quantify- ing maximum willingness to pay, price elasticity, and value-in-use), the competitor perspective (knowl- edge about price levels of competing products and the ability to respond to market changes), and the company perspective (availability of pricing tools, existence of price management processes, and availability of training to develop employee skills in pricing). Current research shows that company- wide pricing capabilities are positively related to firm performance (Liozu & Hinterhuber, 2013b). An in- creasing number of leading companies recognize the strategic role of pricing capabilities. Jeff Immelt, CEO of General Electric, states: ‘‘A good example is what we’re doing to create discipline around pri- cing. . . .When it comes to the prices we pay, we study them, we map them, we work them. But with the prices we charge, we’re too sloppy’’ (Stewart, 2006, p. 65). As a result of this insight Jeff Immelt has appointed a chief pricing officer responsible, among other tasks, for analyzing and developing pricing capabilitities across business units and countries.

A periodic assessment of pricing capabilities al- lows companies to (1) analyze an organization’s pricing capabilities over time and across geograph- ical boundaries, (2) compare pricing capabilities both within and across firms, and (3) plan and imple- ment measures to develop pricing capabilities fur- ther. This benchmarking and improvement of pricing capabilities leads to increased organization- al performance (Dutta, Bergen, Levy, Ritson, & Zbaracki, 2002).

4.3.6. Change management

Innovation in pricing fundamentally engages the or- ganization in a change management process. A new pricing approach is not ‘‘just a change of marketing signals’’ but ‘‘a new way of life’’ (Forbis & Mehta, 1981, p. 42). Engaging the organization to experi- ment with and implement new pricing approaches is thus a change management process that significantly exceeds the complexity of activities such as changing list prices. New pricing approaches frequently re- quire new capabilities, a new organizational struc- ture, different goal and incentive systems, new processes and tools, and new organizational prior- ities. From an organizational perspective, innovation in pricing must be treated like an ongoing change management process as opposed to a project with a finite life.

4.3.7. Pricing experiments: Pricing as organizational learning

Finally, for some leading-edge companies, innova- tion in organizing the pricing function implies treat- ing pricing as organizational learning. Amazon provides an excellent case in point: the company changes the prices of its products several times a day and measures customer satisfaction, purchase patterns, and revenues after each alteration in an ongoing attempt to identify the specific price point which delivers both highest customer satisfaction and profits on any given time segment. For exam- ple, the frequency and magnitude of price changes for newly launched books are greater than those of established books, suggesting that Amazon pla- ces a strong emphasis on experimentation in the period shortly after new titles come to market (Pollono, 2011).

Counterintuitively, frequent price changes can be beneficial for consumers. In one of our recent studies for a diversified energy company that attempted to switch its customers from heating with fuel to heating with environmentally friendly wood pellets, the CEO struggled with the following paradox: customers never complained about fuel prices but complained strongly about occasional price increases of the newly launched, innovative wood pellets. After con- ducting face-to-face interviews and a conjoint anal- ysis with customers, the rationale became clear. Since prices for fuel vary constantly, price memory is impossible. In an attempt to be customer-oriented, the company had kept prices for wood pellets largely constant despite rising input costs. Paradoxically, this policy ended up hurting both customers and the company. Customers became obsessed with price and were very reluctant to switch to innovative products, even though it would have been in their best interest: these innovative wood pellets actually lower total energy costs although they are more expensive on a per unit basis. After our analysis, this company now varies prices for wood pellets randomly around a predefined corridor. The ability of custom- ers to remember prices has dropped substantially, which significantly increases sales of innovative prod- ucts. We emphasize that in this case, stopping cus- tomers from fixating on price translated into higher firm profits as well as lower total costs to customers. Both parties are now better off.

5. Innovation in pricing increases value

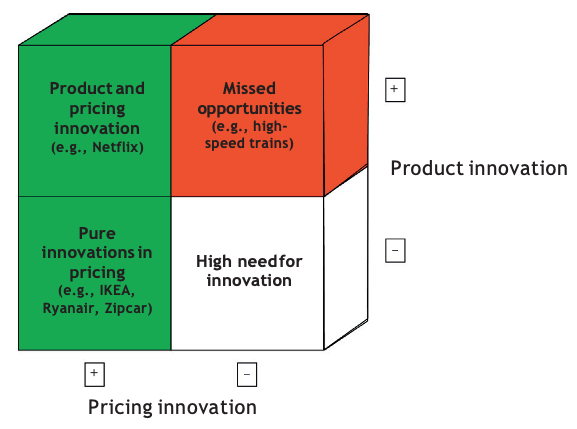

The examples of Ryanair, Zipcar, and General Elec- tric–—as well as our own research–—suggest that innovation in pricing is indeed possible, even in the absence of product innovation. Figure 2 illustrates this point.

Figure 2. Innovation in pricing vs. product innovation

Companies that put strong emphasis on product innovation without similar emphasis on pricing in- novation are missing important opportunities for value capture. For example, instead of pricing high-speed train tickets in Europe in line with airline tickets, many formerly state-owned railway compa- nies have set prices at only moderate premiums over conventional train services. Pure cases of innovation in pricing are related to the majority of examples discussed so far. The underlying driver of superior profitability and customer satisfaction of GE, Zipcar, and others has been the ability of these companies to apply innovation in pricing to a well-established product or service. The final category in the matrix contains cases of joint product and pricing innova- tion. Netflix is a prime example. The company’s founders, annoyed with late fees, pioneered a new pricing structure and a new delivery format (streaming video).

This contraposition of product and pricing inno- vation also helps to spot potential discrepancies: many companies attempt to launch tomorrow’s products with yesterday’s pricing strategies. Com- panies can and should develop unique pricing con- cepts to respond to the unique features of their new products and business models.

Our research certainly does not imply that com- panies should attempt to implement all innovative pricing approaches discussed here. However, our joint experience in academia, in industry, and in advising companies from around the world strongly suggests that all companies–—regardless of size, in- dustry, or geographic location–—will be able to adapt two or three key ideas of our roadmap to design innovative pricing approaches that will increase profits and customer satisfaction.

Appendix

About the research

Our research on innovation in pricing has two objectives. First, we want to document the degree to which an average U.S. firm practices innovation in pricing. Second, we want to provide a state of the art summary of what constitutes innovation in pricing in academic research, as well as managerial practice. To meet our first goal, we conduced 5O interviews in 20 firms in the United States and Europe. Our respondents were CEOs: board members: business-unit managers: and operating managers in sales, marketing, pricing, and finance. We participant in these firms with open–ended questions and asked them to describe in detail pricing decisions and processes at their respective firms. In particular, we probed for instances od innovation in pricing. Consistent with a grounded theory approach, data collection. We listened to the audio recording of each interview several times and read the transcripts of each interview repeatedly. To meet our second goal, we examined pricing practices in 70 large firms in the U.S., Europe, and Asia by analysing publicly available information and by interviewing mangers at pricing workshops that we conduct in Europe and the U.S. We complemented this analysis with a rigorous literature review on cutting-edge academic research on innovation in pricing and marketing.

References

Anderson, E. T., & Simester, D. I. (2003). Effects of $9 price endings on retail sales: Evidence from field experiments. Quantitative Marketing and Economics, 1(1), 93—110.

Best, R. (2012). Market-basedmanagement:Strategiesforgrow- ing customer value and profitability (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Biyalogorsky, E., & Gerstner, E. (2004). Contingent pricing to reduce price risks. Marketing Science, 23(1), 146—155.

Chen, H., Marmorstein, H., Tsiros, M., & Rao, A. (2012). When more is less: The impact of base value neglect on consumer preferences for bonus packs over price discounts. JournalofMarketing, 76(4), 64—77.

Dutta, S., Bergen, M., Levy, D., Ritson, M., & Zbaracki, M. (2002). Pricing as a strategic capability. MIT Sloan ManagementReview, 43(3), 61—66.

Ehm, H. (2010). Overcomingchallengesandhurdleswhileintro- ducingrevenuemanagementinthesemiconductorindustry. Paper presented at the Marcus Evans 2010 Strategic Pricing Conference, Prague.

Fay, S. (2009). Competitive reasons for the name-your-own-price channel. Marketing Letters, 20(3), 277—293.

Forbis, J., & Mehta, N. (1981). Value-based strategies for indus- trial products. Business Horizons, 24(3), 32—42.

Ford, H. (1922). Mylifeandwork. New York: Doubleday.

Goi´c, M., Jerath, K., & Srinivasan, K. (2011). Cross-market dis- counts. Marketing Science, 30(1), 134—148.

Hewitt, C. M., & Patterson, J. M. (1961). Wanted innovations in pricing of services. Business Horizons, 4(2), 93—101.

Hinterhuber, A., & Liozu, S. (2012). Is it time to rethink your pricing strategy? MITSloanManagementReview,53(4), 69—77.

Hinterhuber, A., & Liozu, S. (2013). Innovation in pricing: Con-temporary theories and best practices. London: Routledge.

Jobs, S. (2010, January 27). Steve Jobs announces iPad price. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v= QUuFbrjvTGw

Kadet, A. (2008). Price profiling. SmartMoney,17(5), 81—85.

Kim, H., & Kramer, T. (2006). ‘‘Pay 80%’’ vs. ‘‘Get 20% off’’: The effect of novel discount presentation on consumers’ deal perceptions. Marketing Letters, 17(4), 311—321.