Price setting and price getting require discipline — not luck. Almost any business can improve its pricing performance, provided it approaches pricing in a structured way.

BY ANDREAS HINTERHUBER AND STEPHAN LIOZU

Renowned investoR warren Buffett has said, “the single most important decision in evaluat- ing a business is pricing power. if you’ve got the power to raise prices without losing business to a competitor, you’ve got a very good business. And if you have to have a prayer session before raising the price by 10%, then you’ve got a terrible business.”

Yet pricing receives scant attention in most com- panies. Fewer than 5% of Fortune 500 companies have a full-time function dedicated to pricing, ac- cording to data from the Professional Pricing society, the world’s largest organisation dedicated to pricing. McKinsey & Company has estimated that fewer than 15% of companies do systematic research on this subject.3 And only about 9% of business schools teach pricing, according to the Association to Ad- vance Collegiate schools of Business.4 this neglect is puzzling, as numerous studies have confirmed that pricing has a substantial and immediate effect on company profitability. studies have shown that small variations in price can raise or lower profitability by as much as 20% or 50%.

Pricing Is a Skill

Over the past 18 months, we interviewed 44 manag- ers — from Ceos and CFos to heads of business

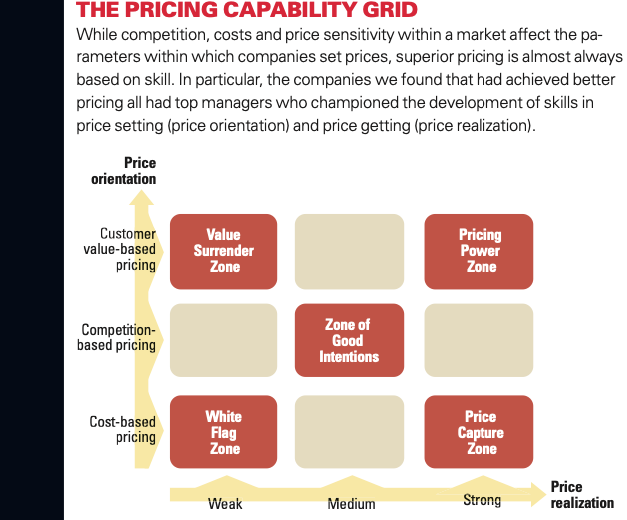

units and professionals in marketing, pricing and finance functions — in 15 U.s.-based industrial companies. (see “About the Research.”) these com- panies varied in size from about 50 to more than 2000 employees and had dramatically different pricing capabilities.6 in the course of this research, we found that pricing power is not destiny, but a learned behavior. while competition, costs and price sensitivity within a market affect the parame- ters within which companies set prices, superior pricing is almost always based on skill. the compa- nies we found that had achieved better pricing all had top managers who championed the develop- ment of skills in price setting (price orientation) and price getting (price realization). Regardless of their industry, the degree to which managers fo- cused on developing these two capabilities correlated to their companies’ success in achieving a better price for their product than their competi- tors. without managerial engagement, companies typically use historical heuristics, such as cost in- formation, to set prices and yield too much pricing authority to the sales force. To gauge the degree to which the companies we

interviewed had developed their pricing function, we created a pricing capability grid. we categorized pricing abilities into five major categories: the pric- ing power zone, the value surrender zone, the price capture zone, the zone of good intentions and the white flag zone. (see “the Pricing Capability Grid.”) Companies in the pricing power zone are able to command significantly higher prices and profitability levels than companies in the white flag zone. we also observed companies that were able to learn their way to superior pricing and saw a number of them undergo a transformation that enabled them to evolve from traditional, cost-based pricing toward higher margin pricing with more disciplined pricing execution.

This article will first discuss the two dimensions of the pricing capability grid: price orientation and price realisation. It then describes the characteristics of the five zones of the pricing capability grid and discusses the transformation process through which companies can improve their pricing capabilities.

ABOUT THE RESEARCH

our goal was to identify the current state of pricing practices in U.S. companies. For this purpose, we contacted the Professional Pricing Society to conduct research on its membership base. To capture contrasting perspectives on pricing within companies, we narrowed our search down to businesses with at least three respondents at three different management levels — at least one respondent from top management (either a CEo, managing director or member of the board of management), at least one respondent from middle management (either a business unit manager or a head of a functional unit), and at least one respondent from lower management (a functional manager). of the 36 companies meeting these criteria, 15 agreed to participate in this research project. at least three interviews were conducted at each company. Respondents included 15 CEos or top executives, 18 sales and marketing managers with full or partial responsibility for pricing and 11 finance and accounting managers with decision-making authority. Seven companies were small (as defined by the U.S. Small Business administration 2007 size standards by industry), having between 50 and 380 employees and eight were medium-sized, with between 900 and 2,200 employees. Six companies (18 interviews) adopted cost-based pricing, five (14 interviews) used competition-based pricing, and four (12 interviews) relied on customer value-based pricing.

Participants in these companies were interviewed with open-ended interview questions that asked them to describe in detail pricing decisions and processes at their respective organizations. Consistent with a grounded theory approach, data analysis commenced simultaneously with data collection. we listened to the audio recordings of each interview several times, and we read the transcripts of each inter- view repeatedly. Three stages of rigorous coding then ensued: open, axial and selective coding. The process resulted in several hundred pages of transcripts and more than 2,554 codable moments.

Price Setting

Price setting, or more formally, price orientation, concerns the methods that companies use to deter- mine final selling prices. Companies differ wildly in their approach to this. Although companies that sell services to individual end-customers, for ex- ample, may be radically different from companies that sell jet engines to sophisticated purchasing centers, and although pricing approaches in india may differ considerably from pricing approaches in italy, academic research and our own findings con- clude that pricing approaches across industries, countries and companies usually fall into one of three buckets: cost-based pricing, competition- based pricing or customer value-based pricing.

Cost-based pricing.

Here, pricing decisions are influenced primarily by accounting data, with the objective of getting a certain return on invest- ment or a certain markup on costs. typical examples of cost-based pricing approaches are cost-plus pricing, target return pricing, markup pricing or break-even pricing. the main weakness of cost-based pricing is that aspects related to demand (willingness to pay, price elasticity) and competition (competitive price levels) are ignored. the main advantage of this approach is that the data you need to set prices are usually easy to find.

2. Competition-based pricing. this approach uses data on competitive price levels or on antici- pated or observed actions of actual or potential competitors as a primary source to determine ap- propriate price levels. the main advantage of this approach is that the competitive situation is taken into account, and the main disadvantage is that as- pects related to the demand function are again ignored. in addition, a strong competitive focus in setting prices can exacerbate the risk of a price war. the 2005-2009 price wars in the domestic car in- dustry in the United states are a good example of this, and similar developments have occurred in the U.s. airline industry. Competition-based pricing approaches are frequently justified on the grounds that price is one of the most important purchase criteria for customers.

3. Customer value-based pricing. this approach, which is also often called “value-based pricing,” uses data on the perceived customer value of the product as the main factor for determining the final selling price. instead of asking, “How can we realize higher prices despite intense competi- tion?” customer value-based pricing asks, “How can we create additional customer value and in- crease customer willingness to pay, despite intense competition?” the subjective and quantified value of a purchase offering to actual and potential cus- tomers is the primary driver in setting prices. Customer value-based pricing approaches are driven by a deep understanding of customer needs, of customer perceptions of value, of price elasticity and of customers’ willingness to pay.

The advantage of customer value-driven pricing approaches is their direct link to the needs of the one constituency paying for the respective goods or services: the customer. the big disadvantage of such approaches is that data on customer preferences, willingness to pay, price elasticity and size of differ- ent market segments are usually hard to find and interpret. Furthermore, customer value-based pricing approaches may lead to relatively high prices, especially for unique products. though that may seem optimal in the short run, these pricing approaches may spur market entry by new entrants or create a risk-free zone for competitors offering comparable products at slightly lower prices.

Finally, it is important to note that it is an error to assume that customers will immediately recognize and pay for a truly innovative and superior product. Marketers must educate customers and communi- cate superior value to customers before linking price to value. Customers must first recognise value in order to be willing to pay for value rather than base their purchase decision solely on price. Despite these shortcomings, many pricing scholars consider customer value base pricing to often e the most preferable way to set new products. some businesspeople have also found that cus- tomer value-based pricing can have important benefits.8 (see “setting Prices Based on Customer value,” p. 72.) it should be noted that customer value-based pricing is especially relevant in highly competitive industries. Although this might seem counterintuitive, we find that many managers in such industries mistakenly assume themselves to be in a “commodity” business. they then neglect the possibility for differentiation and customer value creation and resign themselves to competing solely on price. while we acknowledge that parts of an in- dustry may become heavily price-competitive, we contend that seeing your product as a commodity tends to be a self-fulfilling prophecy. through deeper research into customer needs, almost any product or service can be differentiated. such deeper research can also be a powerful weapon to overcome price pressure by retailers. Armed with data on cus- tomer willingness to pay, price elasticities and perceptions of value and price, manufacturers can demonstrate to retailers the total value jointly created.

Price Getting

Companies also differ in their abilities to realize the prices they set. Price getting (or more formally, price realization) refers to the capabilities and processes that ensure that the price the company gets is as close as possible to the price the company sets. why would the price a company gets differ substantially from the price it sets? inconsistent discount systems, for ex- ample, may explain why otherwise similar customers pay quite different prices. Furthermore, negotiation capabilities as well as lev- els of authority among sales personnel may vary widely, enabling some customers to obtain much more favorable conditions than others. Also, in order to reach sales quota, it-savvy sales associates may cir- cumvent control systems and close deals at unfavorable conditions, while other sales managers will protect prices and margins, preferring to walk away from deals below well-defined target prices. Price-getting capabil- ities are thus fundamentally related to a company’s ability to translate goals into results: they reflect on the ability of a company to enforce — both internally vis- à-vis sales personnel and externally vis-à-vis customers and trade partners — its list prices and to translate these list prices into realised prices.

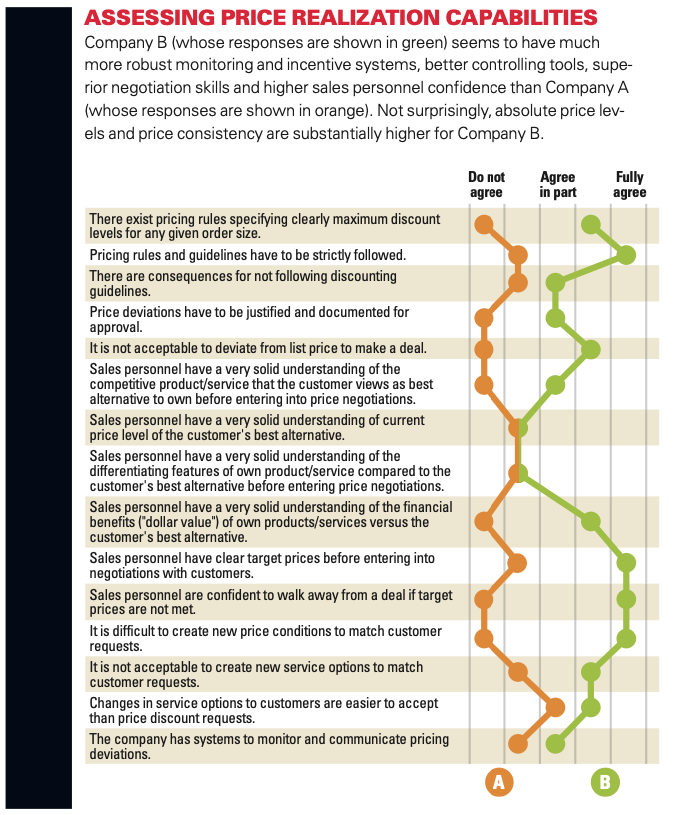

Our research indicates that differences in price- getting capabilities reflect a number of factors:

- the existence of pricing rules specifying maximum discount levels for any given order size;

- the extent to which these rules and guidelines are actually followed;

- the organisational consequences for not following these guidelines;

- the extent to which sales personnel have to justify and ask for approval for deviating from list prices; •the negotiation skills of sales personnel;

- the degree to which sales associates understand a customer’s best available alternative;

- the customer’s maximum willingness to pay and the differential value to customers of the company’s product and service offering;

- the existence of clear target prices before sales personnel enter into negotiations with customers; •the amount of pressure (self-imposed or organisational) that pushes sales personnel to conclude unprofitable deals;

- the self-confidence to walk away from unprofitable deals;

- the extent of free services offered to customers to close a deal;

- and the systems in place to monitor and communi-

cate price deviations to sales personnel, marketing managers and other decision makers.

During the course of our research, we used a spe- cific set of questions as a diagnostic tool to allow executives to assess their price-getting capabilities. (see“AssessingPriceRealizationCapabilities,”p.71.)

SETTING PRICES BASED ON CUSTOMER VALUE

a large European supermarket chain planned to launch a private-label version of a yogurt deliver- ing health benefits. Based on information from cost accounting and using disguised numbers to protect confidentiality, the company decided to launch the product at 1.99. with a cost of goods of 1.29 (and the addition of a predeter- mined markup), this price compared favorably to the price for the branded product of 2.99.

The company’s CEo solicited our view. as a first step, we examined customer percep- tions of value of the branded product and the private label. our initial assumption was that the private label only compared unfavorably with the brand because it lacked a recogniz- able brand name. Surprisingly, however, customer surveys revealed that the private label was superior to the brand in one aspect customers deemed critical: Mothers perceived the private label to be less damaging to the teeth of their children than the branded yogurt, which had a higher sugar content. Mothers were thus reluctant to purchase the branded product as a complement to their kids’ school meal, despite its well-docu- mented health benefits.

Based on an empirical study with custom- ers, we estimated the value of this benefit of the private label to be equal to about 0.30. on the other hand, our research with customers confirmed that the lack of an established brand name reduced the appeal of the private label by about 0.50. overall, we estimated the value of the private label to be about 2.80.

After running simulations in which customer price sensitivity, competitor reactions and other factors were taken into consideration, we recommended a launch price of 2.49. we also recommended a heavy focus on the health benefits as part of the launch campaign. The company largely followed our recommendations. despite the higher price point and thanks to solid communication of the beneficial aspects of the properties of the private label, sales volumes exceeded the vol- ume targets the company had originally set for the product. Profits were nearly sixfold over plan.

The responses from two companies with substan- tially different price-getting capabilities are shown in this exhibit. one company (whose responses are shown in green) seems to have much more robust monitoring and incentive systems, better control- ling tools, superior negotiation skills and higher sales personnel confidence than the other company (whose responses are shown in orange). not sur- prisingly, absolute price levels and price consistency are substantially higher for the former company than for the latter.

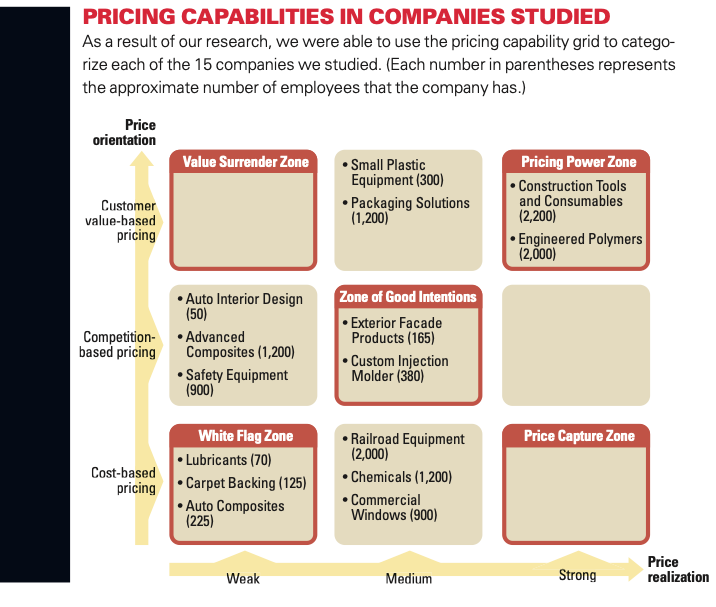

Five Primary zones of Pricing

How do the companies in our research sample dif- fer in their price-orientation and price-realization capabilities? we found significant contrasts be- tween companies with high pricing capabilities and high price realization (power pricing zone) and those with weak pricing capabilities and weak price realization (white flag zone). we classified each of the 15 companies that we studied accord- ing to their price-setting and price-getting capabilities, and we also identified five primary pricing zones. (see “Pricing Capabilities in Com- panies studied,” p. 74.)

1.the Pricing Power zone (high capabilities in price orientation, high capabilities in price realization).

Our research identified a limited number of companies with high pricing power. these com- panies share the following traits: a culture dedicated to pricing, sophisticated tools to quantify customer willingness to pay and customer price elasticities, and robust pricing processes. Perhaps most impor- tant of all, they had champions spreading the diffusion of pricing capabilities throughout the or- ganization. these companies typically have high confidence in their ability to implement list price increases and to defend their price levels vis-à-vis customers. one Ceo in our research commented:

You only need to be brave for one second, and it’s when the guy asks for a discount and you say no. And then you justify it. That takes brav- ery. So how do you get salespeople in a mindset to justify the price? You don’t have to go in there and be Superman for two hours. You have to be Superman for one second.

These companies also have dedicated personnel responsible for pricing, such as a chief pricing officer, a head of revenue management or a director of pric- ing. these senior positions are responsible for implementing robust organizational processes to ensure discipline in price setting and price getting. this means that pricing decisions are embedded in robust structures and processes, rather than being left to the discretion of sales personnel in the field. one pricing manager at a high-performing com- pany using customer value-based pricing said:

We have the prices structured in the system, … the profit desk underneath the pricing team can look to see whether or not the price points are too low, or are at least profitable and value-based enough to go, regardless of what business or trade it is. It’s all set up, up front in the system.

Companies with strong pricing capabilities often have an executive champion driving the price-getting discipline. executives in most other firms are only in- volved in pricing to approve unusual pricing deviations, to participate in large contract negotia- tions or to conduct general business reviews. By contrast, executives in companies with strong pricing power are actively engaged in improving pricing capabilities and in improving overall system effectiveness. these executives thus drive the inter- nalization of customer value-based pricing throughout the company and motivate the organiza- tional changes required to support it. sales and marketing managers we interviewed reported that support and conviction from top leaders is essential to the adoption of customer value-based pricing. As a customer focus manager at a company using cus- tomer value-based pricing remarked:

What made [customer value-based pricing] work was, looking back, … definitely the fact that top management helped sell it, helped, honestly, push it along as well. And over time, it’s proven that they were correct. But without the top man- agement, it wouldn’t have happened.

A caveat: Companies with high pricing power need to carefully balance costs and benefits of the increased complexity of value-based pricing strate- gies. As one senior manager at an industrial company commented:

How many price points do we want to try to manage — how many different price points? Be- cause there is a balance. You can take value and use to every single customer/product combina- tion, and then we’ve got hundreds of thousands of price points we’re trying to manage, which is not good either.

2. the White Flag zone (low capabilities in price orientation, low capabilities in price real- ization). in stark contrast, some companies in our sample did not pay any significant attention to pric- ing. not surprisingly, these companies lagged other companies in key profitability indicators. in these companies, prices do not reflect the customer’s value and willingness to pay; in addition, sales per- sonnel do not have well-crafted guidelines. whether the theoretically established list prices are actually enforced in the field depends in fact mostly on luck and on sales personnel discretion. one Ceo of a company using cost-based pricing commented:

Pricing is based on the gut of our sales person- nel…as long as they’re within their [pricing] latitude to make decisions.

in these companies, discounting is widespread and chaotic. Managers complain about declining price levels but lack the capabilities, vision and in- struments to counter these developments. in essence, these companies abdicate their pricing power to customers.

3. the Value Surrender zone (high capabilities in price orientation, weak capabilities in price realization). in companies in or near this zone, list prices generally reflect customer value well. How- ever, such companies also fail to realize the value they’ve created because discounting guidelines are haphazard. sales personnel are encouraged to ne- gotiate aggressively with customers to bring deals home but lack the information to truly track and

improve price levels. in other words, these compa- nies excel in value creation and delivery, but leave a significant amount of value on the table in negoti- ations with customers or distributors. one sales manager in a company near this zone observed:

The COO had put in these measures to increase sales by discounting, filling up the plant, and he had convinced the people underneath him … that absorption was the name of the game. So now that’s embedded in the culture.

4. the Price Capture zone (low capabilities in price orientation, high capabilities in price real- ization). By contrast, companies in or near this zone have robust systems and processes to minimize unjustified deviations from list prices. However, they typically use rather unsophisticated methods to set those list prices in the first place. these com- panies frequently excel in price execution, but their prices do not reflect the full value that their products and services deliver to their customers. one Ceo of a company using cost-based pricing observed:

The stage gates are you either proceed or don’t pro- ceed based on costing — cost targets. We set a cost target based on the margin expectations, then, of the approximate selling price target. So much more of the formality is around, ‘Are we gonna hit the cost target? Are we way off the cost target?’…. We put more formality around costing analysis, and there is less formality around the pricing.

despite simplistic price-setting mechanisms, companies in or near this zone have robust pro- cesses to realize target list prices with customers. doing so requires a high level of individual and or- ganizational confidence. one manager in a company near this zone observed:

You have to look [customers] in the eye and say, “Ours costs more. This costs more, and it’s worth it. You should pay more for that.” You have to be pretty confident to do that.

5. the zone of Good Intentions (average price orientation, average price realization capabilities). some companies are stuck in an area we call the zone of good intentions.

these companies use slightly more advanced approaches for setting prices. one company, for example, uses dynamic premium pricing linking its own prices dynami- cally to price levels of a well-defined competitor set. these companies also have some systems and pro- cesses in place to limit the discretion of sales personnel in the field and to encourage discipline in price realization. in some cases, a strong produc- tion orientation and thus a strong inward focus are important reasons that the pricing capabilities of these companies have not reached a high level of maturity. As the Ceo of a company using competi- tion-based pricing commented:

Our DNA is manufacturing … I’m very used to standard cost … the very traditional cost plus. It just comes from being a manufacturing com- pany … I think we’re dynamic and moving in the service models but we’ve dragged along this cost-plus kind of a pricing model.

The transformation to Strong Price-orientation and Price-realization Capabilities

virtually all companies aspire to set prices close to the value that their products and services deliver, and virtually all companies aspire to close the gap between list prices and actual in-pocket prices. Yet few compa- nies have successfully made the transition from cost- or competition-based pricing with weak price- realization capabilities to customer value-based price setting with strong price-realization capabilities. en- gaging the organization to implement a new pricing approach is fundamentally a change-management process that significantly exceeds the complexity of activities such as changing list prices.11 new pricing approaches frequently require new organizational priorities, a new organizational structure, new capa- bilities, new processes and tools and different goal and incentive systems.

the interviews we conducted with managers support this view, suggesting that the implementa- tion and internalization of customer value-based pricing requires a deep organizational change that transforms the company’s organizational life and identity as well as the identity of actors within it. Comments from the interviewees suggest that the transformation from pricing based on cost or com- petition to pricing based on customer value is a slow, gradual process.

the implementation and internalization pro- cess of customer value-based pricing is a long, tedious and sometimes painful journey of change for the organization and its actors. this process, which can take four to seven years, requires intense and sustained organizational mobilization to transform established structures, cultures, processes and systems. it requires continual attention, continuous investments and executive sweat eq- uity. Marketers, sellers and developers have to change their business mentality and their frames of reference and embrace new value-related concepts that are expected to become a new way of life.12 they also must learn a new language in order to carry the value message internally and externally. As a result, people either change and become “orga- nizational heroes” or leave the organization.

Because the transition to customer value-based pricing is not easy, companies making such a transi- tion should intentionally design programs focused on building organizational confidence to accelerate members’ buy-in and to boost motivation levels to accept change. when confidence is high, people share beliefs in their collective power to produce de- sired outcomes and ends.13 in its most basic form, organizational efficacy is a sense of “can do.”14 we believe that organizational confidence is a key en- abler of the organizational transformation toward customer value-based pricing.

How to rethink your

Pricing Strategy

How could companies go about rethinking their pricing strategy? the first area that may require a fun- damental rethink is the way companies set prices. Many companies have a significant opportunity to differentiate themselves from competitors by learning how to create, quantify, communicate and capture customer value by implementing customer value- based pricing strategies.

One CEO in our research commented: ‘You only need to be brave for one second, and it’s when the guy asks for a discount and you say no. And then you justify it.’”

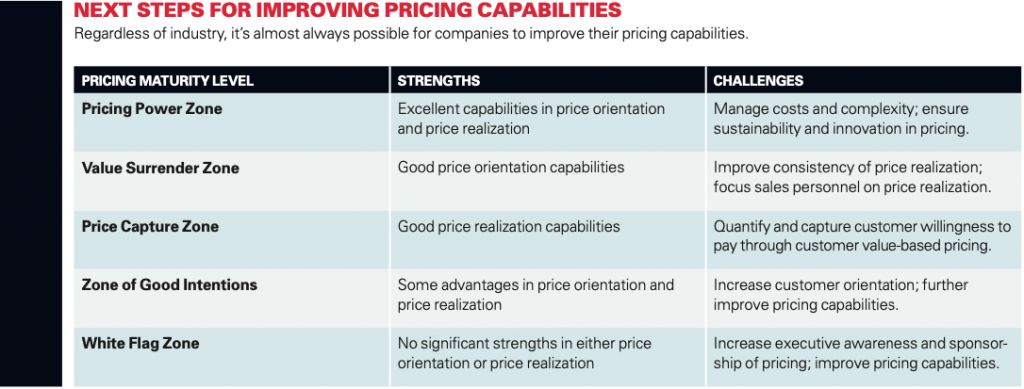

A second area concerns price realization — that is, the process of translating list prices into profitable pocket prices. Here, many com- panies lack the information systems, negotiation capabilities, incentive schemes, controlling tools and sales personnel confidence leading to superior price realization. Small improvements in any of these areas lead to quantifiable results very quickly. (See “Next Steps for Improving Pricing Capabilities.”)

CEO involvement is a critical requirement for ensuring that changes in a company’s pricing strat- egy lead to a true change in the company’s culture. At the same time, the CEO must ensure that these changes are not seen, as too many failed initiatives are, as “just another project.” CEO championing, bundled with organizational confidence, new capa- bilities and transformational change are key catalysts to obtain pricing power.

Andreas Hinterhuber is a partner at Hinterhuber & Partners, a strategy, pricing and leadership consul- tancy based in Innsbruck, Austria. Stephan Liozu is president and CEO of Ardex Americas, a manufac- turer of specialty cements and substrate preparation products based in Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, and a doctoral candidate in management at Case Western Reserve University. Comment on this article at http:// sloanreview.mit.edu/x/53413, or contact the authors at smrfeedback@mit.edu.

REFERENCES

1. A. Frye and D. Campbell, “Buffett Says Pricing Power More Important than Good Management,” February 18, 2011, http://bloomberg.com.

2. K. Mitchell, “The Current State of Pricing Practice in U.S. Firms,” (opening speech Professional Pricing Society Annual Spring Conference, Chicago, May 3-6, 2011).

3. A. Hinterhuber, “Towards Value-Based Pricing: An Inte- grative Framework for Decision Making,” Industrial Marketing Management 33, no. 8 (2004): 765-778.

4. P.H. McCaskey and D.L. Brady, “The Current Status of Course Offerings in Pricing in the Business Curriculum,” Journal of Product and Brand Management 16, no. 5 (2007): 358-361.

5. A. Hinterhuber and M. Bertini, “Profiting When Cus- tomers Choose Value Over Price,” Business Strategy Review 22, no. 1 (spring 2011): 46-49.

6. For more on pricing capabilities, see S. Dutta, M. Ber- gen, D. Levy, M. Ritson and M. Zbaracki, “Pricing as a Strategic Capability,” MIT Sloan Management Review 43, no. 3 (spring 2002): 61-66.

7. J.C. Anderson and J.A. Narus, “Business Marketing: Understand What Customers Value,” Harvard Business Review 76, no. 6 (1998): 53-65; J.C. Anderson, J.A. Narus and W. Van Rossum, “Customer Value Propositions in Business Markets,” Harvard Business Review 84, no. 3 (2006): 91-99; G. Cressman Jr., “Commentary on ‘Indus- trial Pricing: Theory and Managerial Practice,’” Marketing Science 18, no. 3 (1999): 455-457; and B. Shapiro, “Buy Low, Sell High: Creating and Extracting Customer Value by Enhancing Organizational Performance,” Harvard Busi- ness School Note 597-071 (1987).

8. P. Ingenbleek, M. Debruyne, R.T. Frambach and T.M.M. Verhallen, “Successful New Product Pricing Practices: A Contingency Approach,” Marketing Letters 14, no. 4 (2003): 289-305; and P.T.M. Ingenbleek, R.T. Frambach and T.M.M. Verhallen, “The Role of Value-Informed Pric- ing in Market-Oriented Product Innovation Management,” Journal of Product Innovation Manage- ment 27, no. 7 (2010): 1032-1046.

9. See S. Frank, “Applying Six Sigma in Pricing and Reve- nue Management,” Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management 2 (2003): 245-254; or M.S. Sodhi and N.S. Sodhi, “Six Sigma Pricing,” Harvard Business Review 83, no. 5 (May 2005): 135-42.

10. For more on value-based pricing, see T. Nagle, J. Hogan and J. Zale, “The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing: A Guide to Growing More Profitably,” 5th ed. (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2010).

11. As Forbis and Mehta noted as far back as 1981, a new pricing approach is not “just a change of marketing sig- nals” but “a new way of life” See J. Forbis and N. Mehta, “Value-Based Strategies for Industrial Products,” Busi- ness Horizons 24, no. 3 (1981): 32-42.

12. Ibid.

13. J. Bohn, “The Design and Validation of an Instrument to Assess Organizational Efficacy” (PhD diss., University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, 2001).

14. Ibid.

.