Abstract

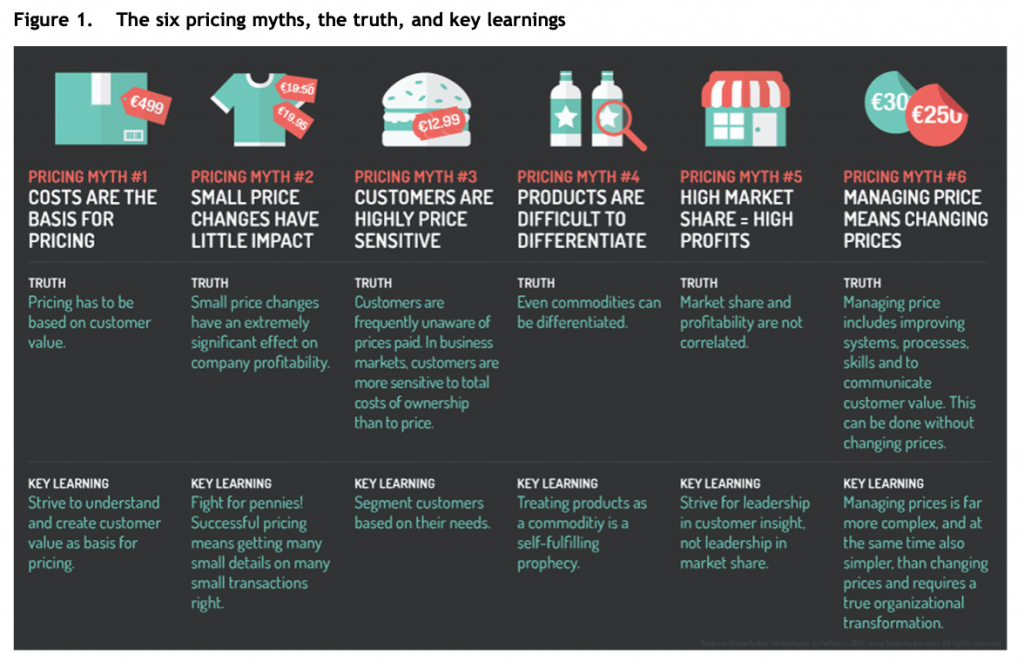

Pricing is the most important driver of profits. Pricing is also, surprisingly, the area most executives overlook when implementing initiatives to increase profits. There is a reason: Research presented in this article suggests that most executives implicitly hold on to a series of weakly held assumptions about pricing that ultimately are self-defeating. These pricing myths are that (1) costs are the basis for price setting, (2) small price changes have little impact on profits, (3) customers are highly price sensitive, (4) products are difficult to differentiate, (5) high market share leads to high profits, and (6) managing price means changing prices. This research shows how executives can overcome these misconceptions and thus implement sustainable profit improvements via pricing.

# 2015 Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Pricing: Guided by principles or driven by myths?

Pricing is, for better or worse, the most important driver of profitability (Schindler, 2011). However, pricing is not yet on most executives’ agendas as a primary concern. Less than 5% of companies have a chief pricing officer (Hinterhuber & Liozu, 2014). For every company that has a chief pricing officer, such as General Electric (GE), there are dozens of Fortune 500 companies–—such as BASF, Volkswagen, Nestle ́, Sony, Toshiba, Daimler, British American Tobacco, and others–—that do not. At the vast ma- jority of companies, pricing falls between the cracks. Everybody, from sales (in negotiating prices with customers) to marketing (in setting list prices)

to finance (in defining payment terms) to controlling (in setting discount levels) to supply chain (in de- termining which customers are eligible for free shipping) to key-account management (in price ne- gotiations with large accounts), is responsible for pricing–—so in the end, of course, nobody is.

How does this self-defeating behavior persist? The extensive research I conducted over the past 5 years (see Appendix) suggests that senior and middle managers unconsciously cling to six pricing myths that kill profits. In this article I explore these myths in detail. And, conversely, I show that an increasing number of highly profitable companies that incorporate well-crafted pricing strategies in their executive agendas have found ways to over- come these myths and increase profits.

So the key question is: Is pricing guided by sound principles or driven by myths? There are abundant examples of companies that fail or merely limp along because they fall victim to the pricing myths. One such dramatic case occurred at General Motors (GM).

1.1. A tale of two companies in the automotive industry

At GM, market share was the number one goal of the company’s executive suite. Legend has it that Rick Wagoner, the former CEO, wore cufflinks engraved with the number 29: the magical market share objective. Bob Lutz, then vice chairman, justified aggressive discounting thus: ‘‘We had to keep the plant going and pump out vehicles to meet the market plan’’ (Simon, 2007, p. 22). Contrast this obsession with volume with the approach of another mass-market producer, Fiat. Sergio Marchionne, the CEO of Fiat Chrysler Automobiles, stated: ‘‘Unprof- itable volume is not volume I want. We have a very good track record for how to destroy an industry–— run the [plants] just for the hell of volume, and you’re finished’’ (Linebaugh & Bennett, 2010, p. B1). Historically dominated by engineers and finance wizards, pricing at GM was heavily cost based. Bribing customers to drive its vehicles off dealers’ lots–—in other words, discounting–—became an integral part of the company’s culture. In a press release following reports that some customers ob- tained more than US$10,000 in discounts despite companywide attempts to cut back on the practice, a GM spokesperson commented: ‘‘It’s to be compet- itive. You have to do something out there’’ (Simon & Reed, 2008, p. 17). GM in the past simply assumed that the first purchase factor of customers was price, followed possibly again by price. Similarly, the company fatally–—and fatalistically–—assumed that cars were seen by customers as a commodity. As a result, GM stopped creating breakthrough cus- tomer value via innovation and made discounts from list prices the main selling point, inviting a series of profit meltdowns. Only recently did GM finally come to grips with the importance of pricing, and exec- utives enthusiastically started by changing list pri- ces and discount structures.

Contrast this approach with the principle-guided approach to pricing of another company in the automotive industry, Continental AG, the second- largest automotive supplier globally, headquartered in Germany. Executives at the company understand that changing prices is the last part of any pricing initiative; Continental AG first improves information systems, pricing processes and tools, incentive sys- tems, and pricing capabilities. Most important, it invests significantly in improving the abilities of its salesforce to practice value-based selling. Armed with relevant and resonating messages, the sales- force is thus superbly able to demonstrate to customers why high prices are more than justified by higher value. The difference in profitability be- tween these two companies is staggering. Both GM and Continental AG are in the automotive industry. The former went bankrupt, largely as a result of ineffective pricing; the latter is among the most profitable and valuable automotive suppliers glob- ally, largely as a result of its disciplined approach to price setting and price getting.

2. The six pricing myths

I contend, as a result of this research, that a signifi- cant reason for GM’s profitability problems–—and, by extension, those of other companies lacking adequate pricing leadership–—was a reliance on outmoded pricing myths that damage profitability; and, conversely, that an important reason for Continental AG’s success is its rigorous attention to pricing: guided by principles, not driven by myths. In the next sections, I look at these myths, state the reasons for discarding each myth (‘truth’), and provide insight on how to build a more viable pricing strategy after each myth is eliminated from practice (‘key learning’). Figure 1 provides an overview.

2.1. The origins of these myths: About the academic research and the managerial practices underpinning these misconceptions

Myths are widely held and unquestioned beliefs that lack scientific basis. The following, counterintuitive observation is important: The actions resulting from an erroneous reliance on myths appear to produce desired outcomes. A scientific analysis, as opposed to a myth-driven analysis, will conclude that these outcomes are not optimal. Consider the following example (adapted from Denrell, 2008): An anthro- pologist visiting a remote tribe observes that each morning members of the tribe sacrifice a goat. This, so the tribe elders say, makes the sun rise. Because food is scarce in this poverty-stricken community, the anthropologist has a simple idea to alleviate the suffering: She proposes that the community refrain from sacrificing the goat for just one day to see if the sun will still rise. In response, tribe elders tell her, terrified: ‘‘In matters of life and death we cannot afford to experiment.’’

This story illustrates the fundamental problem of misconceptions: Decision makers associate actions with a desired outcome and infer a causal relation- ship without attempting to understand whether alternative actions produce a superior outcome.

Similar forces are at work in pricing. Take the first myth, concerning the role of costs in pricing decisions. Before the birth of cost accounting, let alone activity- based costing, establishing accurate costs of goods was a nontrivial problem for executives. In an article in the Harvard Business Review published more than 75 years ago, Nickerson (1940, p. 419) quotes an executive stating that ‘‘not more than 15% of shoe manufacturing companies have anything approaching an accurate knowledge of their real costs.’’ Nickerson also quotes a management engineer–—a consultant in today’s terms–—suggesting that the true figure is at best 8% of companies. Nickerson attributes the high failure rates in the U.S. shoe industry at that time–—more than one in six firms ceased business in the decade spanning 1926 to 1935–—to a lack of understanding of costs. In those early days of business, understanding costs was an asset. Today, as this article illustrates, an obsession with costs is becoming a liability. There are clear parallels between the focus on costs and the sacrifice of the goat: In both cases, decision makers, unwilling to examine causalities, do not even attempt to explore whether an alternative action–—setting prices based on customer willingness to pay or doing nothing, respectively–—will lead to improved outcomes. Decision makers repeat past actions because of an implied past virtue without attempting to understand causal relationships and without

attempting to examine whether alternative ac- tions produce superior outcomes.

The second myth concerns the erroneous belief that small changes in price affect profitability only minimally. This misconception has a simple origin: ignorance. In a widely cited article, Marn and Rosiello (1992) analyzed the financials of nearly 2,500 companies and reported that a 1% change in price increased operating profits by 11% on average. Subsequent studies confirm this finding: small changes in price have a far bigger impact on oper- ating profitability than similar changes in other elements of the marketing mix (Hinterhuber, 2004). Nevertheless, despite robust evidence, managers seem to ignore this fact. More precisely, managers behave as if unaware of the impact of minute changes in price on profits. The result? Pricing receives too little attention by top manage- ment, salespeople are granted too much price ne- gotiation authority, and profitability suffers.

Myth 3 concerns the allegedly high price sensitiv- ity of customers. This myth originates from a false overgeneralization of personal experiences. Manag- ers are intensely involved in all stages of pricing (i.e., price setting, price getting) and know the prices of their own products inside out. Customers must be like themselves, or so the thinking goes. Academic research, by contrast, shows that managers as price setters tend to overestimate the price sensitivity of actual and potential customers (Hinterhuber, 2004). Contrary to managerial intui- tion, academic studies find that minor changes in price do not influence demand (George, Mercer, & Wilson, 1996; Han, Gupta, & Lehmann, 2001). Specif- ically,customersdonotseemtonoticepricevariances under 2% (Monroe, Rikala, & Somervuori, 2015).

Myth 4 suggests that products are difficult to differentiate. This myth stems from the microeco- nomic notion of perfect competition whereby buyers and sellers are numerous, entry is free, information is complete, factors are mobile, trans- action costs do not exist, buyers are rational, and, finally, products are homogenous (Varian, 2014). All models are a simplification of reality. The model of perfect competition is a gross misrepresentation of reality. Managers should discard it. More specifical- ly, studies across a number of industries show that differentiation is possible even in highly competitive industries (Forsyth, Gupta, Haldar, & Marn, 2000).

Myth 5 is about the apparent benefits of market share. As elaborated in detail, this misconception stems from a dated research project of the 1960s advocating a causal link between market share and profitability. Subsequent academic research sug- gests precisely the opposite: The pursuit of market share is detrimental to profitability (Anterasian, Graham, & Money, 1996).

Myth 6 concerns the misconception that manag- ing prices means changing them. This misconception emanates from the notion that management is fun- damentally about realizing change: ‘‘Because busi- ness activity is economic it always attempts to bring about change’’ (Drucker, 1973, p. 66). Successfully managing pricing, by contrast, is not necessarily about changing prices. Todd Snelgrove, the chief value officer of SKF, a world market leader in indus- trial bearings, is adamant that the most important task in industrial selling is communicating value, not necessarily changing prices (Hinterhuber & Snelgrove, 2012):

If you can’t quantify the value of what you’re offering, how [can] you expect a procurement person to do so? If your company creates value then you need to communicate that value, and I have found that if you can quantify it, procure- ment is more willing and able to pay for it.

To summarize, the six misconceptions I discuss in this article originated either from outdated aca- demic research or from unquestioned managerial practices. These misconceptions–—not unlike the myth of the goat sacrifice causing the sun to rise–—produce results, but vastly inferior results than actions guided by scientific principles. This, of course, is true also for pricing. For pricing to act as a driver of superior performance, it has to be guided by scientific principles as opposed to being driven by myths.

2.1.1. Myth 1: Costs are the basis for pricing. Truth: Pricing has to be based on customer value.

- Key Learning: Strive to understand and create customer value, which then serves as the main basis for pricing

According to recent academic research, only about 15% to 20% of companies set their prices based primarily on customer value; the vast majority of companies use cost- or competition-based pricing (Nagle & Holden, 2002). As an example, to compa- nies aiming to grow via international expansion, the Australian Trade Commission presents cost-based pricing as the ‘‘traditional method’’ for calculating export prices (Austrade, 2006, p. 3). The idea that only small enterprises or companies without direct contact to end-users implement cost-based pricing is erroneous. Companies of all sizes and shapes make heavy use of cost-based pricing. German luxury apparel retailer Hugo Boss reached global sales in excess of s1.5 billion while relying on a ‘‘cost plus price formation’’ (Hake, 2009, p. 39). The company has since changed from cost- to value-based pricing; profits, prices, and sales have subsequently grown significantly. Nike, the largest U.S. apparel company and among the 125 largest companies overall, em- ployed a cost-plus pricing model until about 2010: Nike ‘‘simply charged a margin over the cost to manufacture’’ (Barrie, 2014, p.1). The company only recently changed its pricing model from cost- to value-based pricing. Said Nike’s Chief Financial Officer, Don Blair: ‘‘One of the changes that we made over the last 5 years or so is really focusing on the consumer as we set price. . . .it’s about the value equation that we’re trying to create with the consumer’’ (Nike, 2014, p. 11). Analysts attribute a substantial part of Nike’s recent surge in profitabili- ty to this change to a customer value-based pricing strategy (Barrie, 2014).

Sixty years ago, Jules Backman (1953, p. 148), a professor at Columbia Business School, observed: ‘‘The graveyard of business is filled with the skel- etons of companies that attempted to base their prices solely on costs.’’ This should be a wakeup call for executives.

Many companies have failed as a result of cost- based pricing, but cost-based pricing itself is not dead. Currently, few cutting-edge companies prac- tice value-based pricing. At the same time, recent quantitative empirical research suggests that value-based pricing is the only pricing approach positively linked to profitability: Cost- or competi- tion-based pricing lead to lower profitability (Liozu & Hinterhuber, 2013b). In other words, executives are deeply in love with cost-based pricing and the accompanying sense of short-term security this approach provides–—although we now well know that it kills profits.

Consider the following: The amount that car companies charge for metallic paint, depending on car size, ranges between $600 and $1,500. In a recent research and consulting project with a global car manufacturer, we calculated incremental pro- duction costs for metallic paint at approximately $80 per car–—a value, according to industry experts, typical of a midsized car in the global automotive industry. Cars must be painted anyway, and adding metallic pigments to an existing substrate of paints increases production costs only marginally. Then why do car companies not offer this optional feature at, for instance, $120? The reason is, of course, that savvy marketers understand customer willingness to pay (WTP) is unrelated to production costs and depends only on customer perceptions of value. The creation of high customer value allows high prices, even if costs are literally zero.

The fundamental principle of pricing is this: There is no relationship between customer WTP and actual company costs. An understanding of WTP allows companies to charge prices that by far exceed costs but that nonetheless keep customers satisfied. Instead of focusing on costs, executives should focus on understanding and increasing cus- tomer WTP. Costs are not as relevant for pricing purposes as most managers think. Costs provide the lower boundary for prices, and therefore should be calculated. But only an understanding of customer WTP–—that is, an understanding of the total value createdforcustomers–—canprovideguidanceonthe upper boundary of prices.

I remind executives who cling to the apparent sense of security provided by cost-based pricing that it is better to be approximately right than to be precisely wrong. Costs are precise, but they are the wrong basis for setting prices. Value is subjec- tive and perceived; it is less precise, but it is the only relevant basis for pricing.

2.1.2. Myth 2: Small price changes have little impact. Truth: Small price changes have an extremely significant effect on company profitability.

- Key Learning: Fight for pennies! Successful pric- ing means getting many small details on many small transactions right rather than aiming for the one big improvement in one big product or account.

Small changes in price, most executives seem to believe, do little to improve the bottom line. Noth- ing could be further from the truth. Current empiri- cal research suggests that a 1% improvement in net selling prices increases profitability anywhere from 5% to 20% or more (Hinterhuber & Liozu, 2012). A simple example illustrates this point. For a company witha10%operatingprofitability–—forexample,the average U.S. industrial company today–—a 1% im- provement in prices increases operating profitabili- ty to 11%, a 10% improvement over current levels. For companies with lower levels of profitability, the effect of small changes in price on profitability is even larger; for example, for the brand Volkswagen, with an operating profit margin of 3.5% of sales in 2012, a 1% increase in price increases profitability by a staggering 28.5%. Even small improvements in pricing have a strong leverage effect.

If you are a senior executive, ask yourself how your sales managers typically react if customers suggest rounding down the price from, let us say, $10,219 to $10,000 or from s102.5 to s100. Do they give in and put the rounded price on the invoice, or do they stand firm and put the odd-numbered price on the invoice? This simple question could be the litmus test for your salesforce. If your average sales manager insists on the actual sales price, I congrat- ulate you and the sales manager. Well done! If she gives in, you need to do better. A CEO we inter- viewed commented: ‘‘It’s interesting, but our Asian suppliers always insist that we pay our invoices down to the last digit and penny. Asian companies fight for every penny.’’ In pricing, it pays to fight for pennies, and senior executives should teach their salesforces to do so. Todd Snelgrove, the aforementioned chief value officer of SKF, observed: ‘‘Give me a nickel every day. Find ways to convince the customers that we are worth a little bit more every day, and pretty soon these small sums will hit our bottom line in a big way’’ (Hinterhuber & Snelgrove, 2012).

2.1.3. Myth 3: Customers are highly price sensitive. Truth: Customers are frequently unaware of prices paid. In business markets, customers are more sensitive to total costs of ownership than to price.

- Key Learning: Segment customers based on their needs, and address the price-sensitive market segment with a different value proposition than other, benefit-sensitive segments.

In consumer-good markets, customers frequently state that price is a key purchase criterion, but their behavior suggests otherwise.

their behavior suggests otherwise. In a famous study, researchers examined the extent to which supermarket shoppers are aware of prices paid (Dickson & Sawyer, 1990). They found that 50% of customers could not correctly name the price of the item they had placed in their shopping cart just seconds before being interviewed, and that more than half the shoppers who purchased an item on sale were unaware that the price had been reduced. Dozens of subsequent academic studies examining actual purchase data report substantially similar findings.1 Even for frequently purchased products, more than 50% of customers have no idea whatso- ever about prices paid (Gaston-Breton & Raghubir, 2013); among those customers who have at least some price knowledge, the majority of customers actually tend to overestimateprices (Evanschitzky, Kenning, & Vogel, 2004). Finally, the category of shoppers that retailers dread most, the extreme cherry-pickers–—customers shopping only on price and visiting specific retailers with the exclusive intent to purchase loss leaders–—account for less than 2% of shoppers (Talukdar, Gauri, & Grewal, 2010). In conclusion, the behavior of a majority of customers does not suggest that price awareness or price importance is high.

Conversely, this behavior contrasts with what customers themselves think they exhibit. When asked directly about their own decision criteria, many customers list price as a very important, if not the most important, purchase factor (Nagle & Holden, 2002). So, this is the first paradox of price sensitivity: In theory, when asked, customers are highly price sensitive; in practice, when observed, they are not. The second paradox of price sensitivity is that managers think customer price sensitivity is high, whereas in practice customer price sensitivity is low. Numerous studies document that executives perceive customers as increasingly price sensitive, deal prone, and willing to switch to lower price offers as soon as the opportunity arises (Garda & Marn, 1993; Heil & Helsen, 2001; Reimann, Schilke, & Thomas, 2010). In reality, customers are habitual creatures, often exhibiting behavioral patterns with a generally much lower price sensitivity and price awareness than they themselves like to admit.

How can marketing and pricing managers deal with customers having highly malleable preferen- ces? Rather than ascribing to customers a price awareness that even the most deal-prone do not possess, savvy marketers recognize that customers can be divided into distinct segments, each with its own needs and preferences. In the 1960s, academics

recognized that ‘‘the market’’ is an ‘‘unreality,’’ consisting instead of highly distinct segments of customers having very different needs (Weir, 1960, p. 95). Market research is thus a necessary component of every pricing initiative; it allows us to determine the nature, size, and composition of market segments and to estimate how many cus- tomers purchase mainly on price-based criteria. My own studies with hundreds of companies suggest that the size of the purely price-driven market segment is unlikely to account for more than 30% of customers, and in many cases far less. I found that 70% or more of customers seek other benefits such as services, convenience, expertise, speed, quality, customization, and so forth. Once marketers deter- mine the number of customers who want a product or service offering that goes beyond the lowest price, they can offer different product configura- tions at different price points. It is then a strategic choice of the company to decide to cater to purely price-driven customers, if at all. In many cases, after a well-crafted marketing strategy, the compa- ny will decide against it.

What about the differences between business markets’ and consumer markets’ perceptions of price? They are as distinct as night and day. In the former, executives are paid quite handsomely to be price sensitive; in the latter, the sheer number of daily purchase decisions makes it nearly impossible to be fully informed of prices. Recent studies, how- ever, suggest a pattern (Avila, Dodd, Chapman, Mann, & Wahlers, 1993; Ulaga & Eggert, 2006): Although price awareness is high in business mar- kets, price is usually not the most important pur- chase factor. A recent study examined which factors accounted for industrial customers’ decisions to award key-account supplier status to a given suppli- er over a set of alternative candidates (Ulaga & Eggert, 2006). The authors surveyed more than 300 senior purchasing managers and found that costs had the weakest potential to differentiate suppliers from one another (explained variance is 20%). Con- versely, the benefits created had a much larger impact on customer decisions to select a potential supplier as a key supplier (explained variance is approximately 80%). Customers in industrial mar- kets are much more sensitive to benefits than they are to costs.

Furthermore, for many purchases in industrial markets, the initial purchase price represents just 10% of the expenses the customer will incur through- out the product’s life cycle (Kapur & Dedonatis, 2001). Frequently, 90% of expenses are incurred after the initial purchase–—for installation, maintenance, energy, repairs, operation, and product, disposal. Rather than purchase price, industrial purchasing managers thus should be concerned about optimizing total cost of ownership (TCO). For many industrial purchasers, TCO is in fact the most important purchase criterion, ahead of price (Plank & Ferrin, 2002).

Savvy purchasing managers clearly recognize that suboptimizing a component is necessary to optimize the whole. In other words, higher prices for compo- nent products may optimize TCO. Once B2B sales managers recognize that their customers are–—and should be–—interested in TCO, they have a chance to collaboratively identify opportunities for joint value creation or cost reduction to help their customers meet their own goals of a reduction in TCO. Despite its intuitive advantages, TCO is certainly not the most beneficial purchase criteria for industrial buyers. The most advanced industrial suppliers, such as SKF, quantify the total value their product offer brings to potential buyers by determining the sum of quantitative benefits (revenue increase, cost reduc- tion, risk reduction, capital expense savings) and qualitative benefits (brand, expertise, track record, process benefits; Hinterhuber, 2016). SKF, for exam- ple, quantifies the total value of ownership to cus- tomers, a sum that includes the benefits of soft, qualitative advantages, in addition to those of hard, quantitative advantages (Snelgrove, 2012). The pro- cess of value quantification enables SKF to sell its products at a price premium that ranges from 5% to 50% over competitors yet still achieve high sales.

In sum, value creation and differentiation is pos- sible and desirable in industrial markets to at least the same degree as in consumer markets. Few customers purchase on price only, both in B2B and in B2C.

2.1.4. Myth 4: Products are difficult to differentiate. Truth: Even commodities can be differentiated.

- Key Learning: Treating products as a commodity is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Once executives assume that price is the most important purchase factor for customers, it is a very short step to treating products like commodities. Take a look at the U.S. automotive industry. The reason both Chrysler and GM went bankrupt is sim- ple: Executives of both companies believed that the only way to persuade customers to take their cars off dealer lots was through a bribe–—that is, through cashback payments. ‘‘Cars are all alike; customers want a cheap car, and incentives will get customers to buy our cars,’’ top managers at GM may have thought. These thought processes are clearly spec- ulative; however, the annual polls on key purchase reasons conducted by the company itself suggested that in the 5 years preceding bankruptcy, incentives were the most or second most important purchase reason for customers for 3 consecutive years (LaNeve, 2007). Although GM’s legacy costs certainly contributed to its declining competitive- ness, its main weakness was its inability to create meaningful product differentiation.

Once CEOs, marketing managers, designers, and sales executives start treating a product like a commodity, the product in fact quickly becomes just that: a commodity. Leading companies recognize that a commodity is, first of all, a state of mind; there is no product that cannot be differ- entiated.

Consider Shell. One would assume that the physi- cal product of gasoline is a commodity. Not so for Shell. In 2003 the company launched V-Power, a high-octane fuel that promised to bring Formula 1 fuel performance to ordinary drivers. In response to the advertising claim of both increased perfor- mance and reduced consumption, sales of V-Power increased rapidly. In 2010, 7 years after market introduction, V-Power and other differentiated fuels accounted for 15% of all sales and helped Shell increase its market share over rivals. At a price premium of up to 10% over conventional fuel and with minimal incremental costs–—as the company outlines during an investor presentation–—Shell V- Power is hugely profitable (Routs, 2005). Rob Routs, Shell’s head of downstream operations, says: ‘‘The important thing in retail–—any kind of retailing–—is that you keep on changing things; that you keep different customer value propositions, and you keep changing them all the time’’ (Crooks, 2006, p. 12). Does the product indeed lead to lower fuel con- sumption and better performance? When a German journalist visited Mercedes, BMW, and Audi, the near-unanimous answer he received from car man- ufacturers was that engines are optimized for the fuel currently available on the market. A Daimler spokesman said: ‘‘The new gasoline does definitely not enhance the performance of our engines’’ (Beukert, 2003, p. 19).

The key insight of this case study is that even irrelevant differentiation creates customer value and increases customer WTP. All differentiation is based on perceptions. If customers perceive a prod- uct to be differentiated, it is differentiated–—even though, on a technical basis, the actual differentia- tion may be minimal. This case also shows that differentiation is indeed possible and profitable for products that could be perceived as commodi- ties. But, then again, there is no such thing as a commodity, and senior executives should ban this word from their repertoire.

2.1.5. Myth 5: High market share equals high profits. Truth: Market share and profitability are not correlated.

- Key Learning: Strive for leadership in customer insight, not leadership in market share.

Jack Welch, the former CEO of GE, famously insisted that all the company’s business units be either number 1 or number 2 worldwide or risk being disposed of. This requirement formed as a result of the famous PIMS (Profit Impact of Market Strate- gy) studies undertaken in the 1970s and 1980s, which showed a positive relationship between mar- ket share and profitability (Buzzell, Gale, & Sultan, 1975). What was ‘true’ then is bad practice today. Robert Buzzell, the program’s cofounder, declared in 2004 that PIMS was in fact ‘‘effectively out of business’’ (Buzzell, 2004, p. 478). Nevertheless, the obsession with market share is deeply ingrained in CEOs. A cursory analysis of companies such as GM, American Airlines, and Dow compared with compa- nies such as Porsche, Southwest, EasyJet, DuPont, and others shows that there are just as many market share leaders struggling (or approaching bankrupt- cy) as there are market share laggards leading in profitability. Academic research strongly confirms that there is no relationship between market share and profitability (Anterasian et al., 1996).

Kathryn Mikells, CFO of United Airlines, com- mented after the company’s decision to shrink its fleet in order to focus on more profitable customer segments: ‘‘There is a willingness not to be wedded to things that have not worked well–—like market share’’ (Baer, 2009, p. 17). Even in industries with high fixed costs, the pursuit of market share erodes profitabili- ty. Savvy executives know that market share leader- ship simply does not matter. Jørgen Vig Knudstorp, CEO of Lego, says: ‘‘What matters to us is to be the best, not the biggest. We want to be the best playing experience for children, the best supplier to our retailers and the best employer’’ (Milne, 2013, p. 17). Counterintuitively, even executives at Apple, a market share leader in most of its categories, do not chase market share leadership. Tim Cook, CEO of Apple, said: ‘‘Apple will not chase market share for its own sake, instead preferring to keep exciting its customers, and ensuring it can charge a decent profit for doing so’’ (Bradshaw, 2013, p. 15).

Why is the pursuit of market share a killer of profits? An aggressive push for market share encour- ages discounting, which is detrimental to profitabil- ity. Market share goals encourage CEOs to pay too much attention to competitors, thus distracting them from the only constituency that truly matters: customers. Rather than being masters of their own

destinies, companies that blindly pursue market share goals risk becoming slaves to their compet- itors’ whims. As a result, customers are neglected and profits plunge.

Market share is frequently seen as a proxy for pricing power. This may explain why chief execu- tives covet market share leadership. The travails of bankrupt former number-ones such as American Airlines, Blockbuster, Suntech, and Polaroid suggest that market share leadership, by itself, is not worth a cent. Pricing power stems from the ability to create products or services that address customers’ latent needs by understanding customer needs bet- ter than customers themselves understand their own fleeting desires. Superior abilities to create customer value sometimes translate into superior market share2, but not the other way around (Hinterhuber, 2013b). Profits follow leadership in customer insight, not leadership in market share. Leadership in customer insight enables innovation, which in turn leads to pricing power.

How can companies achieve leadership in cus- tomer insight? Current academic research suggests two main approaches: ethnographic research and outcome-driven innovation. Ethnographic research is a method borrowed from cultural anthropology that relies on the systematic recording of human action in natural settings (Arnould & Wallendorf, 1994). Participant observation occurs via long-term immersion, producing ‘‘thick’’ descriptions (Arnould & Wallendorf, 1994, p. 499). The objective is a credible, though not necessarily an exhaustive, in- terpretation of activities aimed at explaining cul- tural variation. Main data sources are observations in context and verbal reports by participants that frequently and purposefully contain overgeneraliza- tions and idiosyncratic accounts. This research method enables researchers to experience the spe- cific, naturally occurring behaviors and conversa- tions of customers in their natural environments. As a result, insight into unsatisfied needs may emerge. This insight can then lead to meaningful innovation.

Outcome-driven innovation relies on a combina- tion of qualitative and quantitative research to un- cover existing, but unsatisfied customer needs (Hinterhuber, 2013a). Researchers first interview customers in order to discover the tasks that custom- ers wish to accomplish; each task is then broken down into a series of desired outcomes; that is, criteria that customers use to evaluate different solutions (Ulwick, 2002). Subsequently, researchers use quan- titative research with much larger samples to priori- tize these outcomes along the two dimensions of satisfaction and importance. Those outcomes that a large percentage of customers rate as both high in importance and low in satisfaction are defined as unmet needs. These outcomes can suggest ideas for breakthrough innovation (Hinterhuber, 2013a).

2.1.6. Myth 6: Managing price means changing prices. Truth: Managing price includes improving systems, processes, skills, and the ability of the salesforce to communicate customer value. In many cases, this can be done without changing prices.

- Key Learning: Managing price is far more com- plex, and at the same time simpler, than changing prices and requires a true organizational trans- formation.

Managing prices, for most of the executives we polled, implies changing prices. Since changing any- thing is difficult–—be it personal habits or business practices–—the prospect of changing prices, includ- ing explaining price changes to sales representatives and customers, is daunting for even the most battle- tested executive. A CEO of a multibillion B2B com- pany asked: ‘‘We cannot change prices short-term; are you still suggesting we need to manage pricing?’’ Managing pricing is indeed what a CEO worth his salt should do.

Managing price is certainly possible without changing prices. In a consulting project with one of the largest global paper companies, sales repre- sentatives faced increasingly aggressive purchasing managers who had been instructed to treat the company’s products as a commodity. These purchas- ing managers negotiated aggressively and threat- ened to switch to lower-priced suppliers unless the sales representatives substantially increased dis- counts. The company faced a dilemma familiar to thousands of executives around the world: Should the company reduce prices and forgo profits in the uncertain hope of maintaining volume, or should it maintain prices and risk losing volume and profits altogether? ‘‘Which option do you pick if both op- tions stink?’’ the company’s CEO asked.

My research and current best practices show that there is a further option, one too often over- looked. That is, a company should quantify the customer benefits of its own products and document that the quantified incremental value provided is greater than the price premium. In the consultancy project with the paper company, we equipped the entire salesforce with argumentation cards and value quantification tools, highlighting the unique customer benefits of the company’s products and quantifying the incremental business impact of the company’s products on the profitability of cus- tomers. What we found was that attributes that the salesforce generally takes for granted have dramat- ic customer benefits. For example, an improved paper consistency eliminates the need for inbound quality control and thus improves customer produc- tivity; an apparently trivial feature such as exact sheet count reduces the amount of stock customers need to keep on hand and improves service levels to their own customers. Even for an apparent com- modity such as paper, the analysis showed, value quantification is possible. As a result of using these argumentation cards, sales representatives now say to purchasing managers: ‘‘Yes, our paper has a price difference of around $100 per ton over our leading competitor. But that is not why we are here today. We can prove to you that if you invest $100 to do business with us, we will deliver to you quantified benefits of $450 per ton.’’ The implied message to aggressive purchasing managers is: ‘‘It would be an error not to purchase the premium-priced product: Our product delivers an incremental ROI of over 300% [implying that the price premium of $100 delivers $450 in incremental cost savings].’’ As a result of this process, unwarranted discounts disappeared almost completely, and the focus of the discussion with customers shifted away from price to the realization of quantified customer benefits. The company’s profitability and customer satisfac- tion levels have soared since then.

Managing price is possible without changing pri- ces. This is what SKF does superbly well. Quantifying value to customers and communicating value to customers both increase customer WTP and reduce the need to discount, thus improving profitability. Of course, an analysis of customer perceived value will, in many cases, reveal instances where prices are misaligned with customer value. If the per- ceived customer value is substantially greater than current prices, there is indeed an opportunity to increase price without losing customers.

3. Why executives cling to destructive myths

Underlying these myths is the assumption that any longstanding practice must have value, otherwise it would disappear. In the words of 1982 Nobel prize winner George Stigler (1992, p. 459): ‘‘Every dura- ble social institution or practice is efficient, or it would not persist over time.’’ This is not true. Bad practices persist for centuries. Slavery, for example, was legal until the late 20th century in the United Arab Emirates. Human sacrifice to end periods of drought is still common practice in India today (Kulkarni, 2013). I use these emotionally distressing examples to make one point: the fact that certain practices have been repeated, even for centuries, does not legitimize them. Only the use of moral, rational, scientific thought can answer the question of whether or not an activity is worth pursuing. Executives have clung to these pricing myths simply because they have persisted over time. Rational, empirical analysis today suggests that the six prac- tices described–—implementing cost-based pricing, ignoring small variations in selling prices, deeming all customers as price sensitive, treating products like commodities, pursuing market share leader- ship, and equating price management with changing prices–—are a recipe for low profitability.

4. Exploring guiding principles of pricing excellence

Pricing is problematic for most executives because it is often left in the hands of ill-prepared sales man- agers while senior executives concentrate on what they perceive as more important drivers of success. This need not be. Senior executives can and should champion pricing in their organizations. Quantitative empirical research suggests that CEO championing of pricing improves pricing capabilities and firm perfor- mance (Liozu & Hinterhuber, 2013a). As a senior management function, CEOs should appoint a Chief Pricing Officer that is capable of driving profits via pricing and capable of arbitrating between units that may hold conflicting views on pricing.

Once executives have liberated themselves from the six myths explicated above, pricing will become a true driver of profits and customer satisfaction. Ex- ploring guiding principles of pricing excellence re- quires that executives critically examine their own deeply held beliefs. This will lead executives to look at pricing in a radically different way. Michael Sandel (2011), a political philosopher, says this about the study of his field, philosophy: ‘‘Philosophy estranges us from the familiar, not by supplying new informa- tion, but by inviting and provoking a new way of seeing. But, and here is the risk, once the familiar turns strange, it is never quite the same again.’’

This is probably valid also for the study of my own field, pricing: the risk of this exploration is that we may find further unquestioned truths in need of examination. Take, for example, the concept of WTP, which traditional marketing theory depicts as the inherent, albeit unobservable, property of goods or services, which should be measured with conjoint analysis and other approaches (Voelckner, 2006). Traditional marketing theory invites us to take an essentially passive approach: to measure what is already there and to derive profitable pricing strategies from this analysis.

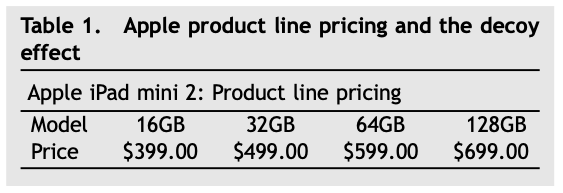

However, leading com- panies such as Apple, which clearly view the concept of WTP as something that can be actively managed and influenced, do not subscribe to this theory. How does Apple create WTP so that customers preferen- tially purchase its most expensive products and shun its entry level products? The company uses an un- derstanding of consumer psychology: the decoy ef- fect. Table 1 shows the prices of different iPad mini 2 WiFi-only models (Apple, 2014).

As memory size doubles, prices increase by an apparently much lower amount. Compared to the entry-level product, the most expensive product looks cheap. This is the decoy effect at work. Apple uses memory size to influence customer perception such that the most expensive product appears un- derpriced. The example suggests that an under- standing of the psychological foundations of pricing allows companies to influence customer perceptions of value and price without actually lowering the price (Hinterhuber, 2015). Put differ- ently, the assumption that WTP is inherent in a product or service is a further misconception. WTP can be created.

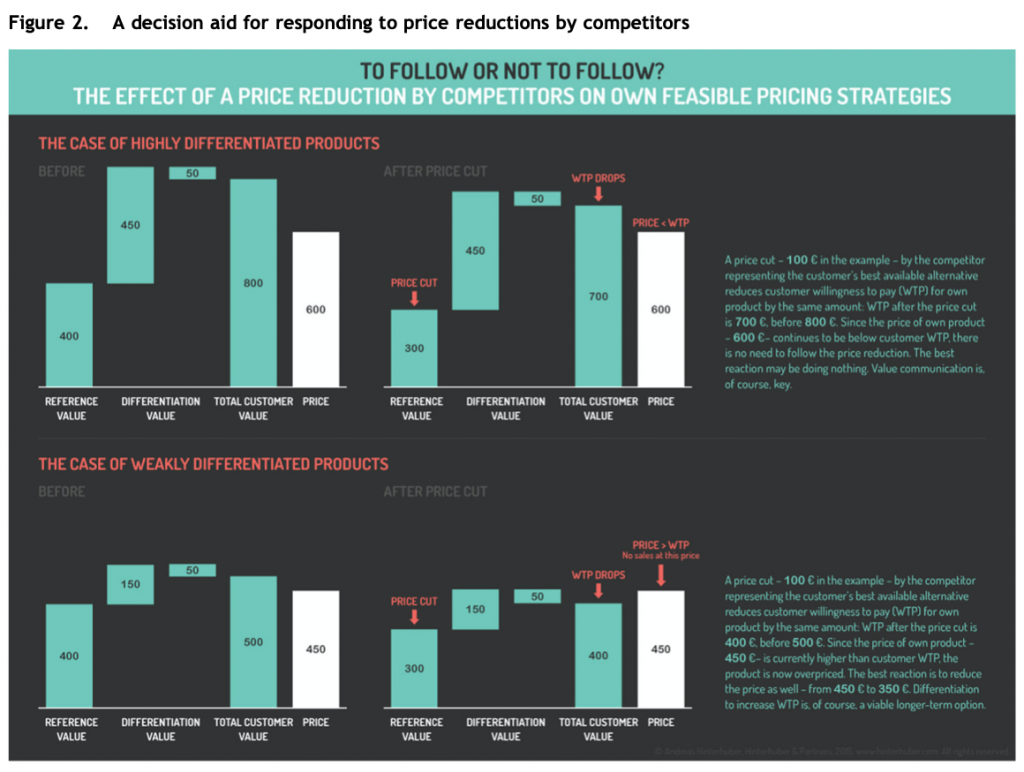

Another example of a pricing misconception that savvy marketers will question is the idea that a price drop by a direct competitor requires a correspond- ing price reduction so that the apparently disrupted equilibrium is restored. This idea is wrong. This notion originates from the hypothesized existence of a ‘‘value equivalence line’’ (Leszinski & Marn, 1997, p. 100). The only scientifically correct re- sponse to a price drop by a competitor is ‘‘it de- pends’’: whether a price cut by a competitor requires a reaction depends, first and foremost, on willingness to pay (i.e., customer value). Demand elasticity needs to be considered only for products with a high WTP. Consider Figure 2.

For highly differentiated products, the best an- swer to a competitor’s price drop may be to do nothing. This principle is illustrated in the upper part of Figure 2. A price cut by the competitor reduces customer WTP for the company’s own product by the same amount; WTP after the price cut is s700 as opposed to the previous s800. Since the price of the company’s own product, s600, continues to be below customer WTP, there is no immediate need to reduce the price. With an inelastic demand, the best reaction may be to do nothing.

Value communication is, of course, key. This may explain why Apple does not react to a price drop by Samsung, its closest competitor.

For weakly differentiated products, the best an- swer to a price drop by a direct competitor is, con- versely, a corresponding price drop. The lower part of Figure 2 illustrates the principle. A price cut by the competitor representing the customer’s best avail- able alternative reduces customer WTP for the com- pany’s own product; WTP after the price cut is s400 as opposed to the previous s500. Since the price of the company’s product, s450, is higher in this exam- ple than customer WTP, the product is now over- priced. The best reaction is to reduce the price; for example, from s450 to s350. This may explain why Samsung reacts to a price drop by HTC or LG, two competitors from which Samsung is perceived as being only weakly differentiated. Differentiation to increase WTP is, of course, a viable longer term option.

Defining the guiding principles of pricing excel- lence is a journey. In this sense, this exploration of pricing myths should be considered a first puck on the ice at the beginning of a very long game.

Acknowledgment

I wish to thank the editor, Marc J. Dollinger, for his constructive comments on earlier versions of this article. I would also like to thank Dr. Thomas Nagle, whose thinking and writing have pro- foundly influenced me and the theory and prac- tice of pricing worldwide.

Appendix. About the research

This research is based on two main sources. One: I analyzed the pricing strategies of over 100 Fortune 500 companies by examining publicly available records including conference presentations, analyst reports, investor presentations, newspaper archives, and others. I complemented this analysis with a rigorous literature review of academic research on company pricing strategies. Two: I collected responses to a poll involving executives that attended open enrollment and inhouse workshops I and my colleagues at Hinterhuber & Partners conducted over the past 5 years. As part of the workshop pre-assignment, executives an- swered a questionnaire consisting of open-ended questions on current pricing practices and strategies, on factors leading to current pricing practices and strategies, on strengths and weak- nesses of current practices, and on other ele- ments related to pricing strategy. In some instances we polled participants orally on these questions during the workshops and transcribed answers concurrently. Respondents in our sample are mostly from companies headquartered in Europe and the U.S., and are mostly from B2B companies; respondents work in marketing including pricing, sales, finance, and general management. In terms of size, participants are from small, medium, and large companies. Respond- ents are from a very broad range of different industries with representatives from nearly all industries as defined, for example, by current Fortune Global 500 lists.

References

Anterasian, C., Graham, J. L., & Money, B. (1996). Are U.S. managers superstitious about market share? MIT Sloan Man-agement Review, 37(4), 66—77.

Apple. (2014). iPadmini2. Retrieved July 1, 2014, from http:// www.apple.com/ipad-mini-2/specs/

Arnould, E. J., & Wallendorf, M. (1994). Market-oriented ethnog- raphy: Interpretation building and marketing strategy formu- lation. Journal of Marketing Research, 31(4), 484—504.

Austrade. (2006, October). Guidetopricingforexport(Australian government White Paper). Canberra, Australia.

Avila, R., Dodd, W., Chapman, J., Mann, K., & Wahlers, R. (1993). Importance of price in industrial buying. ReviewofBusiness,15(2), 34—48.

Backman, J. (1953). Price practices and policies. New York: Ronald.

Baer, J. (2009, April 15). UnitedAirlinesscalesbackitsambitions.

Barrie, L. (2014, July 24). New pricing strategy pays off for Nike. Just-Style. Retrieved March 15, 2015, from http://www. just-style.com/analysis/

new-pricing-strategy-pays-off-for-nike_id122400.aspx Beukert, L. (2003, June 5). Edelsprit lockt Raseran die Zapfsaule. Handelsblatt, Dusseldorf, p. 19.

Bradshaw, T. (2013, August 27). Cheaper iPhone seeks to retain core values. Financial Times, p. 15.

Buzzell, R. (2004). The PIMS program of strategy research: A retrospective appraisal. JournalofBusinessResearch,57(5), 478—483.

Buzzell, R. D., Gale, B. T., & Sultan, R. G. (1975). Market share: A key to profitability. HarvardBusinessReview,53(1), 97—106.

Crooks, E. (2006, October 23). Interview with Rob Routs: ‘‘You have to keep changing’’. Financial Times,12.

Denrell, J. (2008). Superstitious behavior as a byproduct of intelligent adaptation. In G. Hodgkinson & W. Starbuck

Dickson, P., & Sawyer, A. (1990). The price knowledge and search of supermarket shoppers. Journal of Marketing, 54(3), 42—53. Drucker, P. (1973). Management: Tasks, responsibilities,prac-tices. New York: Harper & Row.

Evanschitzky, H., Kenning, P., & Vogel, V. (2004). Consumer price knowledge in the German retail market. Journal of Productand Brand Management, 13(6), 390—405.

Forsyth, J., Gupta, A., Haldar, S., & Marn, M. (2000). Shedding the commodity mind-set. McKinsey Quarterly, 37(4), 78—86.

Garda, R., & Marn, M. (1993). Price wars. McKinsey Quarterly,30(3), 87—100.

Gaston-Breton, C., & Raghubir, P. (2013). Opposing effects of sociodemographic variables on price knowledge. MarketingLetters, 24(1), 29—42.

George, J., Mercer, A., & Wilson, H. (1996). Variations in price elasticities. EuropeanJournalofOperationalResearch,88(1), 13—22.

Hake, B. (2009). Hugo Boss: The use of analytical tools to supplementpricingdecisions. Presentation at the 8th Strate- gic Pricing Conference, Marcus Evans, September 10-11, London, UK.

Han, S., Gupta, S., & Lehmann, D. R. (2001). Consumer price sensitivity and price thresholds. Journal of Retailing, 77(4), 435—456.

Heil, O. P., & Helsen, K. (2001). Toward an understanding of price wars: Their nature and how they erupt. InternationalJournalof Research in Marketing, 18(1—2), 83—98.

Hinterhuber, A. (2004). Towards value-based pricing–—An integra- tive framework for decision making. Industrial MarketingManagement, 33(8), 765—778.

Hinterhuber, A. (2013a). Can competitive advantage be pre- dicted? Towards a predictive definition of competitive advan- tage in the resource-based view of the firm. ManagementDecision, 51(4), 795—812.

Hinterhuber, A., (2013b, July 3). Letters to the editor: By itself, market share leadership isn’t worth a dime. Financial Times 6. Hinterhuber, A. (2016). Value quantification–—The next challenge for B2B selling. In A. Hinterhuber & S. Liozu (Eds.), Pricingand

thesalesforce(pp. 11—23). New York: Routledge.

Hinterhuber, A. (2015). Violations of rational choice principles in pricing decisions. Industrial Marketing Management, 47, 65—74.

Hinterhuber, A., & Liozu, S. (2012). Is it time to rethink your pricing strategy? MITSloanManagementReview,53(4), 69—77.

Hinterhuber, A., & Liozu, S. (2014). Is innovation in pricing your next source of competitive advantage? Business Horizons,57(3), 413—423.

Hinterhuber, A., & Snelgrove, T. (2012). Quantifying and docu- menting value in business markets [Online Course]. Profes- sional Pricing Society. Available at http://www. pricingsociety.com/home/pricing-training/online-pricing- courses/quantifying-and-documenting-value-in-business- markets

Jensen, B., & Grunert, K. (2014). Price knowledge during grocery shopping: What we learn and what we forget. Journal ofRetailing, 90(3), 332—346.

Kapur, S., & Dedonatis, R. (2001). The total cost of ownership vision (White Paper). Dublin: Accenture.

Kulkarni, K. (2013, August 20). Anti-superstition activist Narendra Dabholkar shot dead. Reuters.

LaNeve, M. (2007, June 21). U.S. sales and marketing media briefing. Presentation to General Motors investors, Detroit, Michigan.

Leszinski, R., & Marn, M. V. (1997). Setting value, not price. McKinseyQuarterly,34(1), 98—115.

Linebaugh, K., & Bennett, J. (2010, January 12). Marchionne upends Chrysler’s ways. The Wall Street Journal,B1.

Liozu, S., & Hinterhuber, A. (2013a). CEO championing of pricing, pricing capabilities, and firm performance in industrial firms. Industrial Marketing Management, 42(4), 633—643.

Liozu, S., & Hinterhuber, A. (2013b). Pricing orientation, pricing capabilities, and firm performance. Management Decision,51(33), 594—614.

Marn, M. V., & Rosiello, R. L. (1992). Managing price, gaining profit. Harvard Business Review, 70(5), 84—93.

Milne, R. (2013, February 22). Lego brushes off toy sector gloom.Financial Times,14.

Monroe, K. B., Rikala, V.-M., & Somervuori, O. (2015). Examining the application of behavioral price research in business-to- business markets. Industrial Marketing Management, 47, 620—635.

Nagle, T. T., & Holden, R. K. (2002). Thestrategyandtacticsof pricing: A guide to profitable decision making (3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Nickerson, C. (1940). The cost element in pricing. HarvardBusi-ness Review, 18(4), 417—428.

Nike. (2014). Nike FY 2015 Q2 earnings release conference call transcript, December 18. Beaverton, OR: Author.

Plank, R. E., & Ferrin, B. G. (2002). How manufacturers value purchase offerings: An exploratory study. IndustrialMarketingManagement, 31(5), 457—465.

Reimann, M., Schilke, O., & Thomas, J. S. (2010). Toward an understanding of industry commoditization: Its nature and role in evolving marketing competition. InternationalJournalof Research in Marketing, 27(2), 188—197.

Routs, R. (2005, May 1). Presentation to Shell investors. The Hague, Netherlands.

Schindler, R. (2011). Pricing strategies: A marketingapproach.

Sandel, M. (2011). Justice [Online Course]. Harvard. Retrieved March 1, 2015, from http://www.justiceharvard.org

Simon, B. (2007, November 15). GM launches its last-chance saloon in family car market. Financial Times,22.

Simon, B., & Reed, J. (2008, August 20). GM makes a U-turn over sales incentives. Financial Times,17.

Snelgrove, T. (2012). Value pricing when you understand your customers: Total cost of ownership–—past, present, and future. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 11(1), 76—80.

Stigler, G. (1992). Law or economics. Journal of Law and Eco-nomics, 35(2), 455—468.

Talukdar, D., Gauri, D. K., & Grewal, D. (2010). An empirical analysis of the extreme cherry picking behavior of consumers in the frequently purchased goods market. JournalofRetail-ing, 86(4), 336—354.

Ulaga, W., & Eggert, A. (2006). Value-based differentiation in business markets: Gaining and sustaining key supplier status. Journal of Marketing, 70(1), 119—136.

Ulwick, A. W. (2002). Turn customer input into innovation.

Harvard Business Review, 80(1), 91—97.

Varian, H. R. (2014). Intermediate microeconomics: A modern approach (9th ed.). New York: Norton.

Voelckner, F. (2006). An empirical comparison of methods for measuring consumers’ willingness to pay. MarketingLetters,17(2), 137—149.

Weir, W. (1960). On the writing of advertising. New York: McGraw-Hill.