This article examines the concept of virtual value chain orchestration, an emergent phenomenon of strategizing and organizing. Virtual value chain orchestration is defined as way of creating and capturing value by structuring, coordinating, and integrating

the activities of previously separate markets, and by relating these activities effectively to in-house operations with the aim of developing a network of activities that create fundamentally new markets. The research is based on an in-depth analysis of the agrochemical and biotech industry and is illustrated by two case studies. Consideration is given to steps needed for orchestrating a successful virtual value chain, including the conditions which might indicate when strategic alliances, rather than joint ventures or acquisitions are used for capturing the value created. Based on the preliminary results of the case studies, the article concludes that the orchestration of an extended network of diverse partner companies leads to superior financial results.

????c 2003 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Alliances, mergers and acquisitions and joint ventures are playing an increasingly important role in corporate development, and the growing number of publications on this subject only mirrors this trend. The present article also examines inter-firm alliances, albeit from a different angle. In an empirical study I have observed companies that make use of alliances beyond the scope examined by extant theory, i.e. risk sharing, competence, enhancement or market development.1 Instead, they use their network of alliances, joint ventures, and acquisitions, which has been configured along an extended, cross-industry value chain, to create fundamentally new markets. This “virtual value chain orchestration” is studied in this article, with extended examples from the activities of Monsanto and DuPont in the agrochem- ical-biotechnology sector.

After reviewing existing literature in this field, a framework for value chain orchestration is presented. Following some notes as to research methods, value chain orchestration is illustrated by two empirical case studies, and the relationship between value chain orchestration and financial results is examined. The article concludes with a discussion on the results of the empirical research and suggested directions for future research.

Literature review

In recent years, there has been an unprecedented growth in cor- porate partnering and various forms of external collaboration. Since the 70s and 80s, many companies have given up their long- held beliefs in the benefits of vertical integration, preferring instead to engage in a variety of contractual agreements with other companies. Such inter-firm alliances take on many forms, ranging from outsourcing agreements, strategic alliances and equity joint ventures to reciprocal shareholdings and other, more complex arrangements. The advantages of risk sharing, increased organizational competencies, access to new markets and the possibility of inter-organizational learning have all been cited as possible rationales for this development. After the functional, divisional and matrix structure, organizational scholars view the network organization as an alternative capable of overcoming deficiencies of other structures.2 Recent literature has examined the formation of networks resulting from intense partnering such as strategic blocks or strategic supplier networks.3 Meanwhile managers, such as those at Omnicom, have further developed and adapted this organizational model to industry-specific con- tingencies.4 Recently management scholars have suggested that the networkpositionof a given firm might explain inter-company profitability differences more accurately than a firm’s market position, thereby implying the conceptual superiority of a relational, rather than atomistic approach when examining com- petitive behaviour.5 In such theoretical and empirical studies, knowledge was found to reside not within firms alone, but within networks of companies.6

The access to inter-organizational networks is seen as form of social capital that increases in value with subsequent use.7 Net- work experience defined as knowledge on how to collaborateas well as knowledge gained from collaboration was found to be positively linked to sales growth, innovation rates, or other measures of firm performance.8 However, the predominant focus of the extant literature on strategic alliances and networks is the relationship between the attributes of the partner firms and the resources of the partnering firm in domains of business activity that are critical for competitive success in the current market.

This article examines networks from a different perspective: the creation of inter-company networks purposefully configured along the extended, cross-industry value chain, and managed with the aim of creating fundamentally new markets.

Knowledge wasfound to reside not within firms alone, but within networksof companies

The two distinct tasks of network configuration—i.e. selection of partner companies—and network management—i.e. optimal resource utilization—will be analysed separately in the follow- ing pages.

First, the process of the orchestration of the value chain is defined from a review of the existing literature. Six steps can be distinguished in this process.

- Analysis of internal value chain;

- Analysis of flow of goods & total value created by the extended value chain;

- Identification of ways to increase the amount of value created by the extended value chain;

- Configuration of network around identified opportunities of value creation;

- Identification of ways to capture value created;

- Management of cross-industry value chains.

Analysis of internal value chain

The first step in value chain orchestration is an internal perspec- tive on costs and value added at each step. While nothing new, this exercise provides a first view of the total value added and the effectiveness of internal operations, allowing conclusions to be drawn quickly in comparison to leading competitors. While this exercise is a standard tool in everybody’s toolbox, unfortu- nately most companies simply stop here.

Analysis of flow of goods from primary sourcing to consumption and total value created in the extended value chain

A company’s internal value chain is rarely the only point where value is added to a given product. Consequently, the next step involves an analysis of all upstream or downstream industries which come in contact with the product and add value or could add value to the product. Subsequently, the actual contribution of each industry to the overall value creation is determined or estimated. This step will reveal the amount of value created— measured by EVA (Economic Value Added) or approximated by EBIT (Earnings Before Interest and Taxes)—by each of the industries in the cross-industry value chain.

Identification of ways to increase the amount of value created by the extended value chain

Once the value created presently by the extended value chain has been determined, ways to increase this amount substantially through innovation are identified. The objective is to produce radically innovative ideas on value creation. Value is created by improving the quality of products or services or by reducing costs—potentially at each step of the extended value chain.

The objective is to produce radically innovative ideason value creation

Which company will be able to capture the largest amount of total value created?

To illustrate, let us suppose that a component manufacturer in the automobile industry comes to the market with a device allowing cars to be driven completely on autopilot. The potential value created would be significant, not only for drivers, who would be able to spend their time in cars productively, but also for taxi companies (reduced operational costs), city adminis- trations (less accidents and higher road safety) and even car repair centres, which will no longer have to staff their operations for peaks in customer inflows (usually after working hours), but will be able to electronically ‘ask’ cars to drive themselves in for routine repairs whenever capacity is available.

Any significant innovation in a complex chain raises the ques- tion of rent appropriation: which company will be able to cap- ture the largest amount of total value created? Is it possible that the innovator will be the one to profit least from his own inno- vation? The following three steps ensure that value creation also leads to value capture.

Configuration of network around value creation opportunities

Once potential growth opportunities outside a company’s internal value chain have been identified, links with other com- panies ensure that the potential value created is delivered to cus- tomers. The task of configuring a network can be split in two: selection of partner companies and determination of the most effective form of the relationship with selected partner compa- nies.

For the selection process, as pointed out earlier, recent organization scholars have asserted that competences lie not only within firm boundaries, but also within networks of companies.9 If we follow Andrews in his view of strategy as match between firm competencies and environmental opportunities, network members should be selected both fort heir capacity to add to firm specific competencies and for their capacity to broaden available market opportunities.10

Identification of ways to capture value created: alliances, joint ventures and acquisitions

The question of the form of the relationship with partner compa- nies and the most appropriate ownership structure for various economic transactions has long occupied academic research. In particular, the organizational capability perspective, which sees the firm essentially as a bundle of relatively static and transferable resources,11 views the firm boundary issue as a capability-related issue. Where the firm already has a strong knowledge base, acqui- sition provides an advantage and would be the preferred way of undertaking the activity. On the other hand, the capability constraint becomes important when the firm enters into unfam- iliar areas of activity, where the technological distance of the tar- get activity is high in relation to firm capabilities.12 Empirical studies have confirmed that joint ventures, rather than acqui- sitions, are the preferred vehicle when acquirers do not know

the value of the assets desired, i.e. when they are in different industries.

As value chain orchestration implies the coordination of a wide array of partner companies belonging to different indus- tries, we expect strategic alliances—rather than acquisitions or JVs—to be predominantly employed. While strategic alliances with lower resource commitments and increased flexibility are key for expanding a network across a wide array of unrelated industries, they come with one main disadvantage: lack of con- trol. In instances where value creation is joint but ownership is disjoint, conflicts can arise over the appropriation of resulting rents. Transaction cost theory, in particular, under assumption of bounded rationality and opportunistic behaviour, has ident- ified the conditions for market failure, thus highlighting circum- stances under which internalisation—i.e. acquisition—is more efficient or less costly.13 Difficulties in observation, measurement, and contractual specification increase the potential for opportun- istic behaviour and hence raise transaction costs.

Under these circumstances, transaction cost theory suggests internalisation of concerned activities—indeed it seems likely that, at as concerns about rent appropriation or measuring part- ner companies’ contributions increase, acquisitions or joint ven- tures will tend to predominate, rather than strategic alliances.

Management (“orchestration”) of cross-industry value chains

Once a network of partner companies has been set-up, orches- trators need to coordinate the activities of a wide array of partner companies and relate them effectively to in-house activities. Given the diversity of partner companies, orchestrators need “value creation insights”14 in order to successfully manage and develop the network. In particular, as direct ties serve both as a resource and as a channel for information,15 knowledge transfer between the focal firm and its partners and between partners themselves is critical. As central firms, orchestrators develop ideas in the sense that they take ideas from network partners and add value by developing them further in their own organiza- tions.16

As a result, we expect value chain orchestrators to achieve performance levels significantly higher than those realized by their industry peers. The intense and purposeful development of a wide network of partner companies should give value chain orchestrators the potential to achieve superior operational per- formance compared to companies pursuing other types of strategies.

The role of orchestrators

The roles of four types of orchestrators are explored below: architect, judge, develop and leader.

Orchestrators take ideas from network partners and add value by developing them

Luck and foresight are not mutually exclusive

Network architect—defining the objectives and designating member companies of the network

While the process of setting the objectives and selecting member companies of the network has already been described above, one question has intentionally been left open: to what extent does the evolution of networks follow a premeditated scheme? To which extent can this process be planned?

Hamel examined whether strategic choices were the result of deliberation rather than plain luck:

New business concepts are always, always the result of lucky foresight. The essential insight doesn’t come out of any planning process, it comes from a cocktail of happenstance, desire, curiosity, ambition, and need. But at the end of the day, there has to be a degree of foresight—a sense of where new riches lie. So business concept innovation is always one part fortuity and one part clear-headed vision.17

In our view, deliberation, luck and spontaneous emergence are equally important factors in shaping a network’s overall evol- ution. The choice and availability of some member companies will—ex post facto—turn out to have been pure luck, while other companies become partners in the network after a deliberate planning process. Clearly, luck and foresight are not mutually exclusive – the competencies and market opportunities which become available after the unplanned—‘lucky’—selection of a specific partner company, will then need to be developed and managed in a systematic way in order to add value to the net- work.

Generally, co-evolution plays an important role: in an upward spiralling of continued progression, the selection process of member companies and the evolution of network capabilities lead to a mutually enforcing process of attracting the most valu- able partner companies and of developing overall network capa- bilities.

Network judge—rigorous definition and defence of expected performance standards for membercompanies

Orchestrators define and enforce rigorous performance standards across the network they are steering.18 After all, despite the mul- tiple and heterogeneous contributions of a wide array of part- nering companies, the orchestrator remains the key interface for end customers and is thus fully accountable for the network’s output. Performance standards need to be defined individually for each network member in terms of specific capabilities and global performance objectives. Performance standards are then monitored and adapted, again on an individual basis.

Network developer—nurturing and developing thenetwork’s physical and intellectualassets

Nurturing and developing a network’s physical and non-material assets is another key responsibility that an orchestrator cannot

delegate. In this respect, knowledge management is a central activity. Knowledge management is not limited to making all tacit and explicit knowledge available to network members. It frequently entails spreading the knowledge gained from one part- ner company to other alliance partners in order to gain access to their specific knowledge.

In this sense, knowledge gained in the network is used as cur- rency to increase the available knowledge base even further. A manager expressed this view in the following way: “It is important to be an active participant at the leading edge of world science. Effective technical interchange requires that the indus- trial organization have its own basis research results … to use as a currency for exchange”.

Just as people-management implies a responsibility for nurtur- ing and developing competencies and capabilities of collabor- ators, so orchestrators have the responsibility for developing the capabilities of partner companies in order to ensure that, even in fast-changing environmental conditions, the overall goals of the network can still be achieved.

Charismatic leader of the network—solicitingvoluntary participation and rewardingperformance

In a hierarchical context, cooperation is achieved—and can even be enforced—by means of the hierarchical relationship itself. In a context characterized far more by heterarchy and self-governance than hierarchical relationships,19 the ability to solicit spontaneous collaboration is vital. The success of networks is closely tied to the extent to which an active and frequently unpredictable life takes place at the boundaries of the network. Central firms have the key responsibility of motivating partner firms to collaborate on overall network priorities. Sometimes this can involve yielding power and control to smaller members: when key competencies are developed at the outer bounds of large networks, central companies can allow smaller companies to temporarily steer the development of the whole network. Clarifying roles is another important task: orchestrators should specify the contributions they expect from each partner company, whether as contri- butions to the orchestrator, or to the network/to other network members. In this way, orchestrators create and manage a rich texture of interactions in the network, and rather than viewing network members as parts of the external market, they tend to view them as part of their own organization, as part of their own value chain.20

Orchestrators are keen to instil an element of reciprocity in their relationships with partner companies: as orchestrators they are successful only together with their partners, and the success of partner companies comes with the success of the orchestrator. They also take a long-term view on the relationship and expect partner companies to do likewise. In this way, partner companies understand they will benefit in the long run for the open sharing of ideas, even if immediate compensation is sometimes not poss- ible. Finally, for key assets or capabilities, central companies expect partner companies to take on an active role in further developing specific competencies.

Sometimes this can involve yielding power and control to smaller members

Method overview

The setting of this study is the global agrochemical and biotech- nology industry, a slowly growing market valued at around $ 30 billion per year.21

The author has a professional background in this industry and has been involved as project manager in the field of agrochemical biotechnology. Publicly available data were used to gain an understanding of the competitive dynamics of the industry, to detect patterns of competitive behavior and to understand and predict company strategies: published interviews with company executives, research reports by investment banks, HBS case stud- ies, newspaper articles, and published research on the industry are the only sources of the data reported here.

If the competitive dynamics of the industry are analyzed, two broad patterns can be observed. The first, consolidation, is the option pursued by the majority of competitors: the 15 largest companies in 1991 had been acquired or merged into 8 global companies just a decade later. The second option, intense alliance activity, has been masterfully implemented by two companies, Monsanto and DuPont. In an effort to overcome the boundaries of an essentially stagnating market, these two companies have been particularly adept in forging alliances with a wide and diverse set of partner companies.

The way in which the two companies integrate their traditional agrochemical operations with biotechnology in a highly sophisti- cated network of alliances, joint ventures and acquisitions along an extended value chain is the main focus of the present article, their patterns of action being described as “virtual value chain orchestration”.

Orchestration in action—the empirical evidence

Monsanto

Monsanto’s search for growth beyond industry boundaries was triggered in 1995 when Monsanto’s leadership team, under the direction of its CEO, Robert Shapiro, drafted a new strategy for the company. The team recognized that an increasing world population, the ongoing pollution of the environment especially in developing countries, and decreasing acreages of arable land would put the world’s environment under increasing pressure over the next decades. Shapiro’s vision of “sustainable growth” lead the company to a fundamental shift in its strategic approach: rather than producing chemicals sprayed on fields, the company would produce information—genetic information—to be incor- porated in plants which would add value for the farmer and the consumer. “A closed system like the earth cannot withstand a systematic increase of material things, but it can support exponential increases in information and knowledge”, Shapiro says. Biotechnology was the mean to achieve this vision.22

Arnold Donald, CEO of Monsanto Agro, expressed the incum- bent paradigm shift in the following way:

Traditionally, agricultural inputs were produced, distributed, and marketed as separate products: seed was produced and distributed by seed companies, herbicides, insecticidesby chemical companies, and quality improvements were done by processing companies (I foresee a system)where these separate channels would merge. Through biotechnology the insecticide is hosted by the plant itself. Quality can be built in directly intothegenomeoftheplant.Wewillwitnessaparadigmshift.

Monsanto also recognized that this paradigm shift required a fundamentally different approach to the traditional food chain: rather than viewing it as a system of clearly separated steps where each company would focus on optimising its specific contri- bution, Monsanto recognized the opportunity of seeing it as interconnected where the potential existed for a selected number of companies to directly or indirectly influence the whole chain. For this to become true, a network of partner companies would be needed—on all levels along the extended, cross-industry value chain.

Monsanto adopts a combination of strategic, financial, cul- tural, and technical criteria in the selection of potential part- ner companies:

Strategiccriteriaensure that the long-term vision of Monsanto of global sustainability is being translated into a set of com- petence and opportunity-based indicators. Competence-based indicators evaluate potential partners in terms of assets, capabili- ties, and resources needed by Monsanto to complete the virtual value chain. Opportunity-based indicators aim to estimate the size of the market which is expected to become available with specific partner companies.

Financial criteria ensure that the relationship with partner companies allows specific payback criteria to be met. Here, NPV, Free Cash Flow, and Economic Value Added-projections were frequently adopted, and where possible, a real option approach was used to integrate more traditional financial criteria.

Cultural criteria ensure that core values, operating mech- anisms, and decision processes are compatible between the com- panies. Far more than a soft issue, the managers interviewed for this study again and again repeated that the basis of the most successful partnership was frequently laid in this cultural due- diligence process. The following comment by a manager by one of Monsanto’s partner companies is typical of effective partner- ships: “We fully trust the guys at Monsanto. So we will open up our kimono quickly and get to a meaningful exchange of information far quicker than with [company X]”. Where the reciprocal exchange and transfer of competences and information is key motivator of the partnership, the creation of an atmosphere conducive to the sharing of ideas is essential.

Genetic information incorporated in plant to add value for farmer and consumer

In a last step, a set of technicalindicatorsprofiles the capabili- ties of partner companies against the leading edge of science and against their closest competitors. The goal here is to rank poten- tial partners from a purely technical perspective.

Potential partners are screened against all criteria. It is important to note that Monsanto takes on an active role in screening and selecting partner companies. Even if preferred partner companies are known to be currently unavailable, they are nevertheless included in the database and ranked according to the criteria discussed, in order to be able to act quickly should circumstances change. As one manager said: “It is generally an indicator of a weak selection process if the people from [invest- ment bankers] have to come up to you to propose a list of attractive partners. We, on the other hand, screen potential part- ners long before anybody knows that they are available in order to have something to convince them to work with us or to be ready when they are available.”

Value capture

Peter Drucker has said that the largest profits go to the company that provides the crucial missing piece that completes a system.23 In the case of the global agrochemical-biotech industry the cru- cial missing element needed by all other companies is represented by the seed industry. One analyst put it this way: “A new gene is worthless, without a quality seed base and the infrastructure to deliver it.”24

Seed companies incorporate the genes containing the desired properties into the seeds creating a crop with distinctive traits, thereby differentiating what without them would remain just another ordinary commodity. In addition, recent patent infringe- ment suits with hundreds of million dollars at stake between seed companies who had licensed out their technology and agrochem- ical companies, demonstrate the risk of entering license agree- ments where intellectual property rights and their financial value are difficult to asses and where the value created is huge.

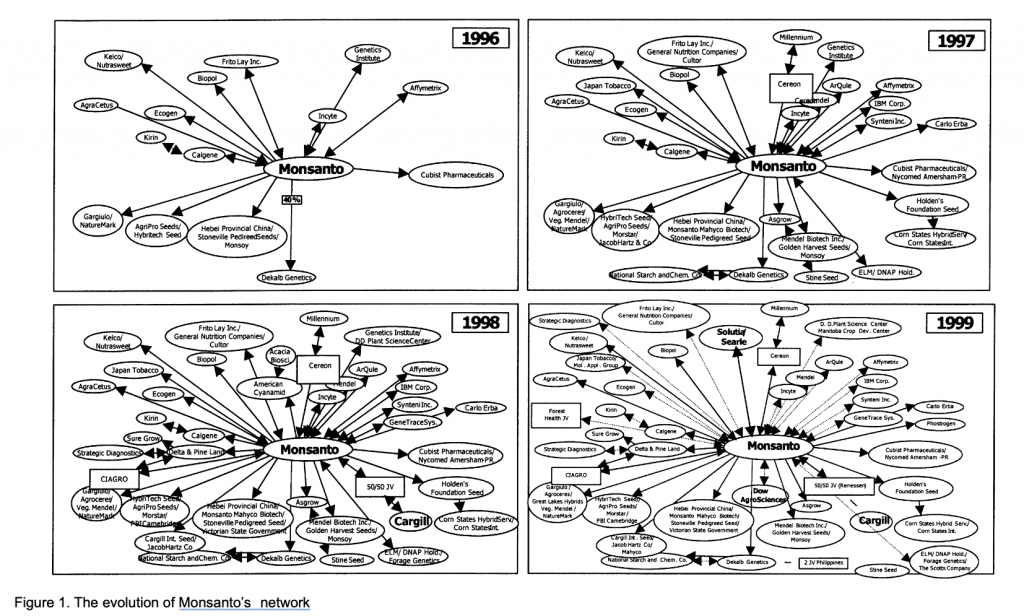

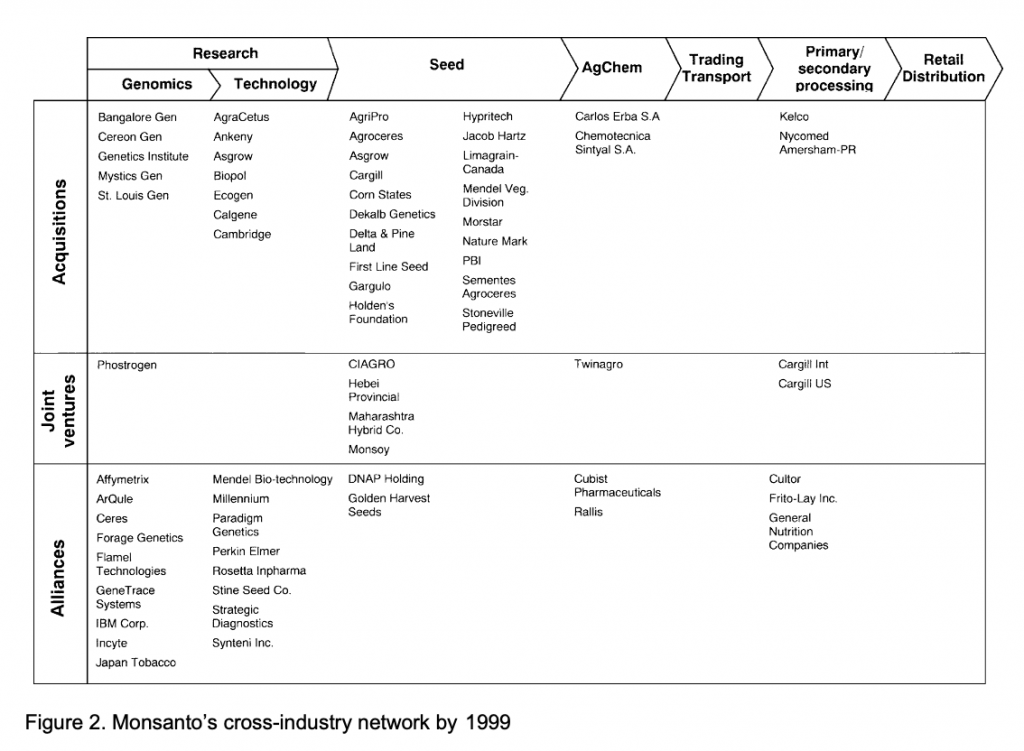

Monsanto was one of the earliest companies to invest heavily in mergers and acquisitions (M&A’s), roughly $ 8 billion from 1994–1999 — a significant amount, considering Monsanto’s pre- tax income of less than $ 200 million during that period. By following a strategy of value chain orchestration, Monsanto cre- ated a dense network of partner companies covering every step of the extended value chain. (see Figures 1 and 2)

The largest profits go to the company that provides the crucial missing piece that completes a system

Alliances and acquisitions at the level of food processing com- panies ensure identity preservation of value-added crops, a criti- cal element of Monsanto’s strategy: if enhanced crops lead to food with health traits (“nutraceuticals”), these crops have to be kept separate from commodity crops at all stages of the value chain.

In retrospect it is interesting to see how an aggressive strategy has been implemented with success. In a speech given in 1993

The CEO outlined 10 major research targets to be met by 2000.25 Today we can compare these targets—all related to future launches of biotech products—with results actually achieved. It can be concluded that the company has actually met 70% of the targets originally set. Furthermore, more than 75% of all world- wide biotech sales in 2000 are from Monsanto — up from 50% in 1997 and 0% in 1993.

DuPont

Following the 1998 spin-off of its petrol subsidiary Conoco (in what was then Wall Street’s largest-ever IPO), Du Pont’s CEO Charles Holliday considered his company’s next moves, certain that its future lay predominantly in biotechnology. Within DuPont, research efforts in biotech had been exploratory until the mid 1980s. In 1986, however, biotech started to receive increased management attention and financial resources, and the company saw that, eventually, plants could be transformed into “tiny factories”, capable of enhancing the value of agricultural products in many ways. It recognised the potential of biotechnol- ogy to fundamentally reshape current industry value chains. Stephen Potter, DuPont vice president of strategy and business development, stated:

We are moving from an asset-based industry into a knowl- edge business. This will redefine and reshape our industry’s value chains. The application of bioscience, genomics, and technology will dramatically alter the ability to create and capture value.

Plant could be transformed into ”tiny factories”

Many of the best opportunities will arise from the convergence of two or more formerly separated fields. In short, we will have to figure out how to use the existing systems better to create more value and to cut costs.

Dick Reason, CEO of DuPont-Pioneer, said:

In the auto industry, there is a connection between what end-users need and what suppliers supply. Automakers do not buy plastic as a commodity—they buy certain plastics for certain purposes. Grain processors, on the other hand, traditionally have not been able to buy grain based on the requirements of the markets. But the new crop technology will allow it to be done.

In contrast to Monsanto’s strategy of investing in both input traits (biotech products aimed at increasing farmers’ productivity) and output traits (biotech products for consumers), DuPont focuses exclusively on output traits.

According to several executives interviewed at DuPont, the company believes that input traits merely replace existing pro- ducts and revenue streams, while output traits truly create new value. Charles Holliday said: “We focus our technology on improving the ultimate use of plants which we call output traits—on the consumer benefit from plant modification.”26 The company recognized than an aging population and an increas- ingly pleasure-oriented society demanded food that not only did not damage their health, but also contributed to a healthy life- style.

The company’s focus on output traits means that the company is focusing on products with health claims, with improved flav- our and enhanced functionality. In October 2000, the US FDA (Food and Drug Administration) approved a health claim asso- ciated with the benefits of soya protein in reducing coronary heart disease. Thus consumers drinking soybean milk will be aiming to reduce their cholesterol levels and increase life expect- ancy. While still on a small scale, this example clearly illustrates the direction the company aims to take.

Valuecapture

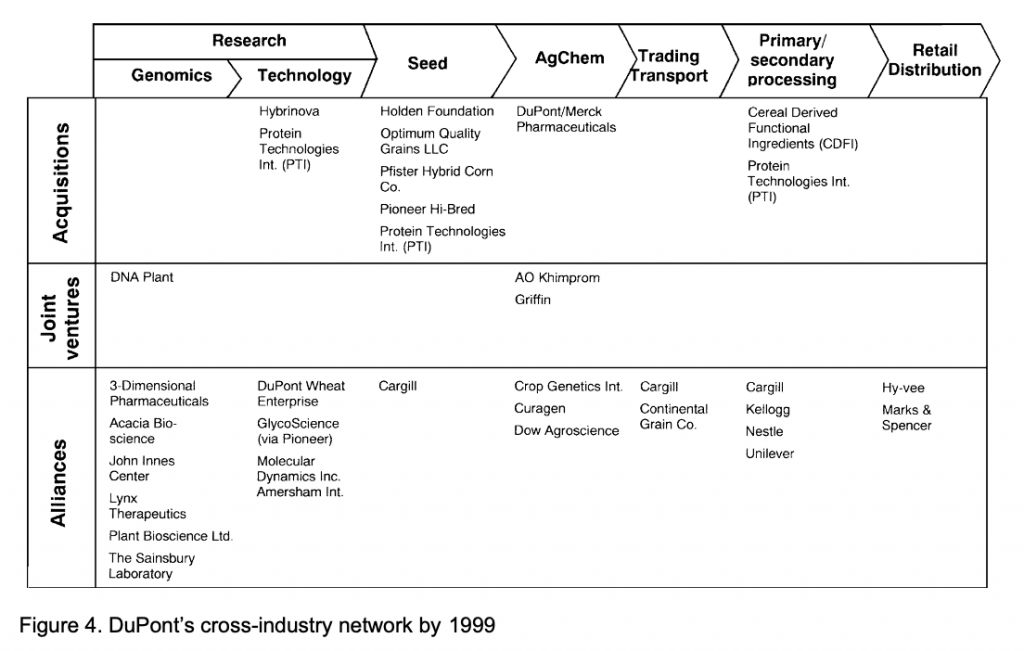

Holliday recognized that “to deliver output traits, one has to have a delivery mechanism, and that’s seed.” In 1998, DuPont acquired Pioneer, a leading US seed company, and following a series of other, smaller acquisitions, the company is recognized today as the largest seed company in the world. Michael Ricciuto, head of DuPont biotech communication, said: “The business sys- tem just does not exist for distributing and marketing branded products. So we are creating it.” In the creation of the new busi- ness system involving a broad range of partner companies DuPont relies heavily on strategic alliances. The company

The need to preserve indetity explains heavy alliance activity along the extended value chain

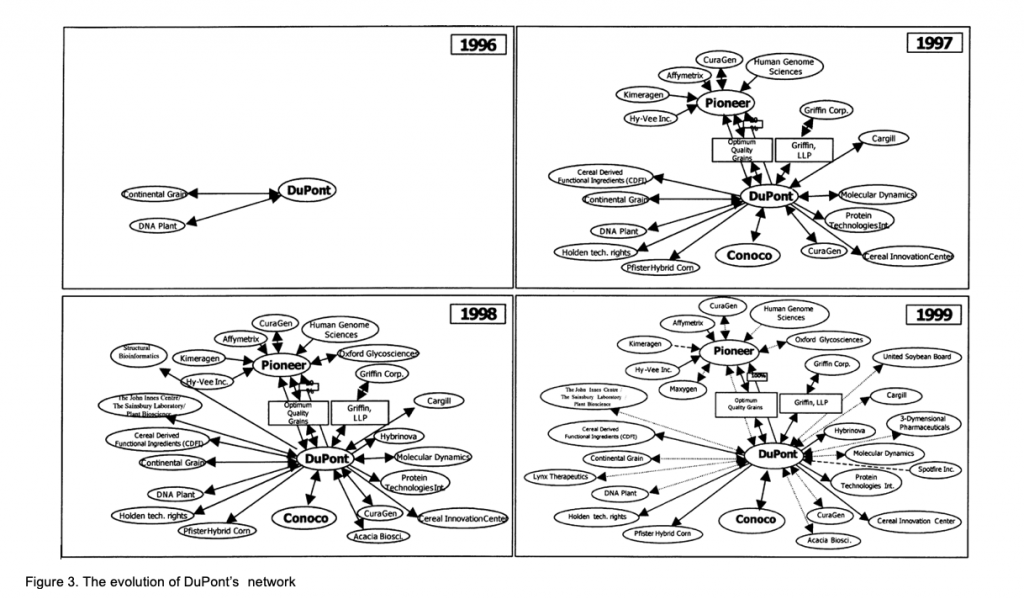

“Virtual integration” stands for the company’s commitment of long-term cooperative arrangements with independent firms.27 (see Figures 3 and 4)

In this strategy the need to preserve identity explains the heavy alliance activity along all stages of the extended value chain. In particular, alliances with partners such as Unilever (food processing) and Marks & Spencer (retail) ensure that the com- pany’s products will be delivered to customers through well- defined and value-adding channels.

The underlying logic of identifying the most desirable partner companies was the logic of virtual value chain orchestration. The extended, cross-industry value chain and the purpose of creating fundamentally new markets became the framework for ident- ifying, evaluating and selecting alliance partner companies. Ulti- mately, DuPont “covered” all steps of the extended value chain with a dense network of R&D collaborations, joint ventures, stra- tegic alliances, and acquisitions.

Performance standards with partner companies are managed through service level agreements, i.e. predefined commitments on expected outcomes between DuPont and partner companies. Star-performers can thus earn a more central and hence more important role in the network, while under-performing compa- nies are expelled if they do not reach specified milestones.

To evaluate a potential partner, DuPont looks first at the part- ner itself and identifies skills in four major areas: technology, intellectual property (patents), product development, and market access. It then evaluates the partner based on how compatible it is with DuPont in each of these areas. Once this is done, the partner is then evaluated along a set of general criteria, including

Star performance earn a more central role in the network

commitment to research, culture, global, scope, financial strength, and any history of alliances with DuPont or other part- ners. Although technical criteria were important, the concept of culture is central to DuPont’s evaluation. The company feels that a long-term partnership is based on trust and that it is difficult to work with organisations that view significant aspects of the business, such as product strategies or customer relationships, in ways different from its own.

Other players in the industry

Although a detailed report about competitive strategies of other industry participants is not part of this paper, a considerable amount of data on the alliance and acquisition activity between 1996 and 1999 in the industry was gathered. Main sources of information were industry journals Agrowand ChemicalWeek— where all significant alliance and acquisition activities are reported—annual reports, research reports by investment banks, and field interviews. Table 1 below summarizes commonalities and differences in the two companies’ approach to the orches- tration of virtual value chains, as well noting the levels of alliance, joint venture and acquisitions activity in the industry in general for the period analysed.

As regards alliance activity, it has been suggested earlier that orchestrators would exhibit a significantly higher alliance activity along the extended value chain than other companies. The data above confirm that Monsanto (25 alliances) and DuPont (21 alliances) exhibit a significantly higher alliance activity than their industry peers (13 alliances on average).

This article has also suggested that acquisitions, rather than strategic alliances would be employed at the point of the extended value chain where uncertainties regarding rent appro- priation were greatest—a point represented in the global agroch- emical and biotech industry by the seed industry. The available empirical data seem to confirm this point, showing that, at seed industry level, Monsanto has a total of 19 acquisitions and 2 alliances, DuPont has a total of 5 acquisitions and 1 alliance, while other companies have on average 2 acquisitions and 2 alliances.

Financial results

A word of caution is necessary before interpreting financial results of orchestrators and other companies in our study. As mentioned already, investments in biotechnology are long-term investments where, so far, costs and revenues have not materialized in the same way. Monsanto’s CEO stated that, even after the significant investments of his company in biotechnol- ogy, “a commercial breakthrough [in output traits] was still a long way off”.28 Tom McKillop, at that time CEO of Zeneca, echoed his words: he recognized that biotechnology would only add significant contributions to the bottom line in the mid to long-term.

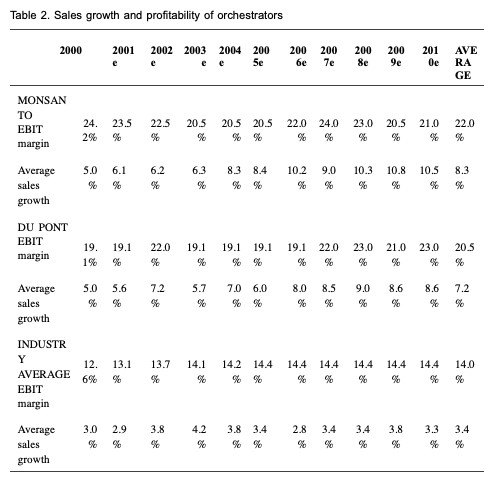

Thus, rather than analysing present financial results, this arti- cle looks at expected financial results, and here, research reports by investment banks provide useful data. Research reports by Merrill Lynch, HSBC, Deutsche Bank, and Morgan Stanley were scanned for data on the global agrochemical industry, as well as on data for expected profits and sales for Monsanto and DuPont.29 Table 2 summarizes estimates by investment banks on the expected profitability and growth of Monsanto, DuPont, and their industry peers.

Expected sales growth for the industry (year 2000–2010) is 3.4% per year, while Monsanto and DuPont are expected to growth by 8.3% and 7.2%, respectively. The expected profitabil- ity in the industry (defined as EBIT/sales) is 14.0%, while Mon- santo and DuPont are expected to realize profitability margins of 22.0% and 20.5%, respectively. The data from the two case studies thus seems to indicate that value chain orchestrators are expected to exhibit significantly higher sales growth and profita- bility ratios than their industry peers.

On a final note, it is worth recording that biotechnology was initially met with scepticism—especially in Europe and Japan. Today, by contrast, it seems that solid scientific research has been successful in convincing consumers worldwide about the poten- tial benefits of the responsible use of agricultural biotechnology.30 This change of sentiment is also reflected in industrial sales stat- istics: for 2001 ChemicalWeekreported declining sales in conven- tional agrochemical markets and strongly increasing sales in biotech products.

Discussion and conclusions

This article has explored the theory and practice of an emergent phenomenon of organizing and strategizing. Virtual value chain orchestration has been defined as a way to create and capture value by structuring, coordinating, and integrating activities of previously unrelated markets and by effectively relating these activities to in-house operations with the aim of developing a network of activities that create fundamentally new markets.

The dynamics of inter-organizational relationships, and especially the challenges linked to the configuration and manage- ment of an extended network of partner companies, were illus- trated by two companies operating in the highly dynamic environment of the global agrochemical and biotech industry. The relationship between strategic orientation (i.e. virtual value chain orchestration vs. “traditional” strategies) and financial results has been explored, and companies implementing a strat- egy of value chain orchestration were found to exhibit signifi- cantly higher sales growth and profitability rates than their indus- try peers.

In a review of network studies Oliver and Ebers remarked that, despite the growing number of publications on inter-organiza- tional networks, only limited attention had been given to out- come variables, such as cost/price, revenues, learning and inno- vation.31 The two illustrative case studies have shed some light on the relationship between the network structures and financial results of focal firms, and specifically, the analysis of the global agrochemical industry has shown that value chain orchestration and the creative management of a wide array of partner compa- nies along the extended value chain indeed seem to translate into superior financial performance.

The study has several limitations. First, the superior results determined for orchestrators are not actual results, but expected results: efforts have been made to use a reliable and unbiased source (investment banks), but of course there is no guarantee that these results will actually be met.

Second, the evidence presented here is anecdotal, rather than systematically scientifically grounded. More research is needed to empirically ground the concept of value chain orchestration, possibly in other industry contexts using historical financial results. Despite these limitations, the model of value chain orches

tration can be seen as an emerging way of organizing and strateg- izing, which underscores the importance of relationships, com- petencies, and systemic innovation. It probably represents a further step beyond the model of virtual outsourcing in the sense that a compelling and clear-cut logic underlies the evolution of a web of partners. As stated above, this model of organizing and strategizing is still emergent, in the sense that we need more empirical research to undermine its foundation.

This article should therefore be considered as a first puck on the ice at the beginning of a very long game.

A compelling and clear cut logic underlies the evolution of a web of parters

References

- W. Powell, Learning from collaboration—knowledge and networks in the biotechnology and pharmaceutical indus- tries, CaliforniaManagementReview40(3), 228–240 (1998).

- H. H. Hinterhuber and B. M. Levin, Strategic networks—the organization of the future, Long Range Planning27(3), 43– 53 (1994).

- J. Jarillo, On strategic networks, Strategic Management Jour- nal9(1), 31–41 (1988).

- J. Kelley, Energizing the network—an interview with Tom Watson, Chief Growth Officer, Omnicom Group, LongRange Planning33(2), 173–183 (2000).

- R. Gulati, N. Nohria and A. Zaheer, Strategic networks, Stra- tegicManagementJournal21(3), 203–215 (2000).

- B. Kogut, The network as knowledge—generative rules and the emergence of structure, Strategic Management Journal 21(3), 405–425 (2000).

- J. Coleman, Social capital in the creation of human capital, American Journal of Sociology 94, 95–120 (1988).

- W. Powell, K. Koput, L. Smith-Doerr and J. Owen-Smith, Net- work position and firm performance—organizational returns to collaboration in the biotechnology industry, Researchinthe SociologyofOrganizations16, 129–159 (1999); J. Hagedorn and

J. Schakenraad, The effect of strategic technology alliances on company performance, Strategic Management Journal 15(4), 291–309 (1994); T. Stuart, Interorganizational alliances and the performance of firms: a study of growth and innovation rates in a high-technology industry, Strategic Management Journal 21(8), 791–811 (2000); S. Chung, Performance effects of coop- erative strategies among investment banking firms—a loglinear analysis of organizational exchange networks, Social Networks 18, 121–148 (1996).

- B. Kogut. see Reference 6

- K. Andrews, The Concepts of Corporate Strategy, McGraw Hill, New York (1980).

- C. K. Prahalad and G. Hamel, The core competence of the corporation, Harvard Business Review 68(3), 79–91 (1990),

K. Cool and D. Schendel, Performance differences among strategic group members, Strategic Management Journal 9(3), 207–223 (1988)

- A. Madhok, Cost, value and foreign market entry mode— the transaction and the firm, Strategic ManagementJournal 18(1), 39–61 (1997).

- O. E. Williamson, MarketsandHierarchies, The Free Press, New York, NY (1975).

- A. Campbell, M. Goold and M. Alexander, The value of the parent company, California Management Review38(1), 79– 97 (1995).

- G. Ahuja, Collaboration networks, structural holes and inno- vation—a longitudinal study, Administrative Science Quar- terly45, 425–455 (2000).

- G. Lorenzoni and C. Baden-Fuller, Creating a strategic center to manage a web of partners, CaliforniaManagementReview 37(1), 146–163 (1995), here p. 150.

- G. Hamel, LeadingtheRevolution, Harvard Business School, Boston, MA (2000), 23.

- R. Haecki and J. Lighton, The future of the networked com- pany, TheMcKinseyQuarterly3, 26–39 (2001).

- M. Markus, B. Manville and C. Agres, What makes a virtual organization work?, Sloan Management Review 42(1), 13– 26 (2000).

- G. Lorenzoni and C. Baden-Fuller, Creating a strategic center to manage a web of partners, CaliforniaManagementReview 37(1), 146–163 (1995), here p. 160.

- Phillips McDougall, Agriservice—Industry Overview, United Publishers, London (2001).

- J. Magretta, Growth through global sustainability: an inter- view with Monsanto’s CEO Robert B Shapiro, HarvardBusi- nessReview75(January–February), 79–88 (1997).

- P. Drucker, quoted in G. Gilder, Telecoms—How Infinite BandwidthWillRevolutionizeourWorld, The Free Press, New York (2000), 186.

- Furman Selz, The Agbiotech and Seed Industry, Investment Report, New York (1998).

- R. Goldberg and T. Urban, Monsanto Co.: The Coming of AgeofBiotechnology, Harvard Business School Case Number: 9-596-034 (1995).

- Chad Holliday, Chairman and CEO, DuPont, Speech at the, Sanford-Bernstein Strategic Decisions Conference, New York City, June 8 (2000).

- J. West, C. Kasper, E.I. DuPont de Nemours and Co. (B); Harvard Business School Case Number 9-600-051 (1999).

- J. Magretta, : Growth through global sustainability: an inter- view with Monsanto’s CEO Robert B. Shapiro, Harvard Busi- nessReview75(January–February), 79–88 (1997).

- Merrill Lynch In-depth Report, Monsanto (5 October 2001); Merrill Lynch, Research Report—The Food Industry (10 December 1998), HSBC Equity Research, Syngenta—Seeds of Success (March 2002); HSBC Equity Research, Awaiting Syng- enta, A review of the global agrochemicals industry (July 2000), Deutsche Bank Equity Research, DuPont (10 May 2001); Deut- sche Bank Equity Research, BASF—The Four Drivers of Value (20 April 2001), Morgan Stanley Equity Research, Bayer—Earn- ings Downgraded (12 November 2001); Morgan Stanley Equity Research, Aventis (8 November 2001); Morgan Stanley Equity Research, Bayer Company Update—Phoenix Rising from the Baycol Ashes? (18 December 2001).

- L. Yan and P. Kerr, Genetically engineered crops: Their potential use for improvement of human nutrition, Nutrition Review60(5), 135–141 (2000).

- A. Oliver and M. Ebers, Networking network studies—an analysis of conceptual configurations in the study of inter- organizational relationships, Organization Studies 19(4), 549–583 (1998).