Our masterpiece, expanded in its II edition:

This book provides frameworks and best practices to master the key, fundamental challenge of pricing in B2B: quantifying and documenting value. Most managers are too obsessed with price and not enough with value: academics and practitioners from companies such as DHL, SKF and others show how to get the balance right.

Chapter 1 – Introduction

Quantifying and documenting value in business markets

By Hinterhuber Andreas and Snelgrove Todd C.

The essential challenge that sales and marketing managers in industrial markets face is this: converting their firm’s own competitive advantages into quantified, monetary customer benefits. Doing so enables business-to-business (B2B) sales and marketing personnel to justify price differences between competing offers with a difference in monetary value. A disguised project example illustrates this fundamental principle of value quantification.

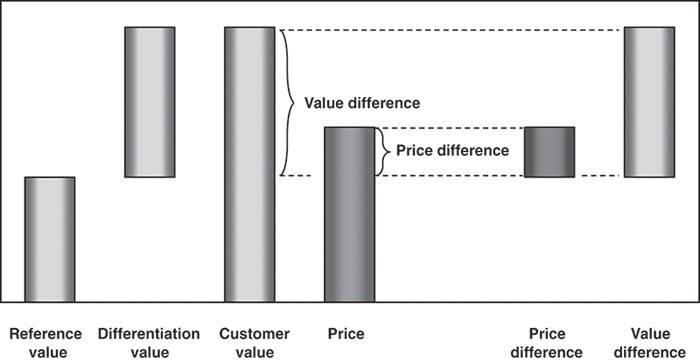

Customer value is the sum of (a) the price of the customer’s best available alternative and (b) the subjective, customer-specific value of all the differentiating features that distinguish the supplier’s own offering from the customer’s best available alternative (Nagle and Holden 2002). Customer value is thus the quantified sum of the customer-specific benefits accruing to purchasers as a result of purchasing the offering. This sum is the maximum price that rational buyers will be prepared to pay. The price difference between the supplier’s own offering and the customer’s best available alternative is then related to the difference in value between the two offerings (see Figure 1.1).

Value quantification thus enables suppliers to perform return on investment calculations: the price difference between two offerings is the investment customers make to obtain the quantified, monetary customer benefits identified.

Value quantification is arguably the most important capability in B2B selling. It is also a capability that many companies in industrial markets lack (Anderson, Kumar, and Narus 2007); these companies, however, are at least conscious of their lack in value quantification capabilities and recognize the potential benefits of developing them (Töytäri and Rajala 2015).

The contents of the book

This book is one of the few books—possibly the only book—exclusively dedicated to the topic of value quantification in business markets. Individuals from leading institutions, such as the Kellogg School of Management, Ca’ Foscari University Venice, Boston College, Aalto University, the University of Tennessee, the Ohio State University, Case Western Reserve University, Deloitte, and Hinterhuber & Partners, and practitioners from companies including SKF, DHL, Borealis, the Strategic Account Management Association (SAMA), and Parker Hannifin provide best practices, case studies, tools, and principles of value quantification in industrial markets. The book has two implicit premises. First, selling should be based on value first, then price. Second, procurement should also be based on value first, then price. Buyers and sellers in business markets must focus first on value, then on price, in order to increase performance.

A unique feature of this book is that it explores the topic of value quantification from the perspective of both sellers and buyers in industrial markets.

The buyer perspective: In many organizations, sourcing criteria were heavily weighted towards tangible criteria, such as price, quality and delivery. Practitioners as well as procurement scholars have started to explore procurement models that consider an array of tangible and intangible benefits in sourcing decisions. Several chapters in this book present procurement frameworks that consider the total value of supplier contributions in the offer evaluation process. This book also presents anecdotal evidence that sourcing criteria considering the total value of benefits lead to increased firm performance and allow to create value – e.g. environmental benefits – that traditional procurement models typically do not create. We need, however, more research. Specifically, we need research developing these metrics, such as total value of ownership or total value contribution models (see chapter 13) that reflect innovation, management capabilities, sustainability, and other elements beyond quality, price, and delivery. We also need quantitative research exploring the consequences of the use of total value of ownership models by procurement on company performance and on value creation.

On to the perspective of sales: there is now increasingly robust evidence that value quantification capabilities are beneficial for firm performance. The core focus of this book are case studies, best practices and recent research findings exploring the factors that enable companies to acquire and successfully deploy value quantification capabilities.

The structure of the book

“Part I—Introduction” contains this introductory chapter, by Andreas Hinterhuber and Todd Snelgrove.

“Part II—Selling value: Value quantification capabilities” contains several chapters that address the capabilities needed to quantify and document value in business markets.

The opening chapter “Value first, then price: the new paradigm of B2B buying and selling” by Andreas Hinterhuber, Todd Snelgrove and Bo-Inge Stensson sets the frame for the entire book. Our key argument is this: Most companies today take an inherently adversarial approach to buying and selling in industrial markets, thereby missing out on opportunities for joint value creation with customers and suppliers. Sales as well as procurement are too obsessed with price and not enough with value. We present a set of principles that put joint value creation at the centre of the relationship with customers and suppliers. With respect to customers, the value quantification capability is the most important competency of the sales function, i.e. the ability to translate a firm’s competitive advantages into one quantified, monetary value reflecting both qualitative as well as quantitative customer benefits. Several chapters in this book (all in section III) provide examples of quantified value propositions, for B2B services as well as for B2B products. With value quantification capabilities (sales) and total value of ownership models (procurement) the key element of relationship with both customers and suppliers is value first, then price.

In an interview, Robert Russell and Andreas Hinterhuber explore several key issues related to value quantification. First, since pricing is always the result of a chain of prior activities, optimizing pricing cannot involve price optimization alone. Managers should instead map the most important processes related to pricing, in B2B typically the offer development process. Once this process is mapped, once bad and best practices along every process step are described, and, finally, once managers have compared their own current practices with best practices, then opportunities to improve profits via pricing are typically identified very effectively. This interview also explores the topic of change management in the context of value-based pricing and value quantification. Hinterhuber suggests that companies benefit from holding an underlying, implicit organizational change management theory in order to effectively implement value quantification: useful theories include the influence model by McKinsey & Company (Keller and Price 2011), Kotter’s eight-step model of organizational transformation (Kotter 1995), the switch model by the Heath brothers (Heath and Heath 2010), and the free-spaces theory of social movement research (Kellogg 2008). These theories, examples and recent research related to pricing strategy implementation are discussed in detail in another book (Hinterhuber & Liozu, 2020).

In the subsequent interview, “Muddling through on customer value in business markets?,” Todd Snelgrove and James Anderson discuss two key aspects of value quantification: how to develop value quantification capabilities and how to quantify value for weakly differentiated products. The authors first suggest that companies move through three stages when building value quantification capabilities: in the first stage—the prove-the-concept stage—companies undertake several value quantification projects in order to learn the concepts, process, and tools and to obtain the benefits from these pilot projects. In the second stage—the build-the-structure-and-culture stage—companies significantly expand the scope of value quantification: they train experts, build value quantification tools and repositories of case studies, conduct more projects, measure the success consistently, and link value quantification with other projects, such as the new product development process. In the third stage—the sustain-the-advantage stage—companies institutionalize value quantification by, for example, appointing champions whose primary responsibility is value quantification. A second insight of this interview is that value quantification differs between strategic and non-strategic products, that is, between products that contribute significantly to differentiating the customer’s offering and those that do not: Value quantification is suitable for strategic products. For non-strategic products, by contrast, detailed value quantification is typically not possible and not even desired by customers; instead, suppliers provide customers with resonating arguments such as generic case studies—in the author’s terms: with a tiebreaker—able to shift the balance in the supplier’s favor. In sum: the more a supplier’s product contributes to creating meaningful differentiation in the customer’s products, the more value quantification has to be detailed, collaborative, and customer-specific.

In the interview “Nurturing value quantification capabilities in strategic account managers,” Andreas Hinterhuber, Todd Snelgrove, and Bernard Quancard discuss the importance of value quantification capabilities for strategic account managers. Quancard is adamant: Only about 30% of account managers truly create value for customers; the remaining 70% are merely commercial coordinators. In order to truly create value, value quantification capabilities are fundamentally important. These capabilities are valuable and rare: Only 10% of companies, Quancard suggests, are able to translate into monetary terms the value they create for customers. Quancard further observes thoughtfully in what may become a noteworthy quote: “Most projects go to request for proposal (RFP), because there is not a compelling monetization of the value.” In this view, a request for proposal is thus nothing else than a reflection of the supplier’s inability to quantify value. Quantified value propositions, accompanied by approximate price ranges for competitive products, eliminate the need for a request for proposal and allow the isolation of collaborative customer relationships from competition. This interview also sheds light on the antecedents of value quantification capabilities: active listening skills, cross-functional collaboration, financial acumen, and an unlimited curiosity. CEO support is, like in all cases of organizational transformation, essential. A further element to consider in the process of building value quantification capabilities is the selection of customers. Not all large customers are or will be receptive to joint value creation and value quantification. Those that are not should not be strategic accounts, irrespective of their purchase volume. Account managers thus need to define criteria for determining which large customers are strategic. Only with these strategic accounts should collaborative value quantification occur.

In “Salesforce confidence and proficiency—The main cornerstone of effective customer value management” Gary Kleiner presents a case study on customer value quantification. This chapter stresses the importance of sales force confidence in addition to the required technical skills in order to effectively and convincingly quantify customer value.

“Part III—Selling value: Best practices in value quantification” contains six chapters highlighting best practices in value quantification. In “Value quantification—Processes and best practices to document and quantify value in B2B,” Andreas Hinterhuber presents the results of a study on value quantification capabilities in European and U.S.-based B2B companies. This chapter presents five key steps that can guide managers in industrial companies in quantifying value: generation of customer insight, value creation through meaningful differentiation and collaboration, value proposition development, value quantification, and implementation/documentation. This chapter also highlights several case studies of quantified customer value propositions, SKF and SAP among them. SKF is, of course, a special case: Todd Snelgrove has played a leading role in quantifying and documenting value for thousands of use cases at SKF.

In “Quantifying your value so customers are willing and able to pay for it,” Todd Snelgrove highlights that quantified value that relies on tangible evidence and that has a high likelihood of occurrence acts as a very strong purchase motivator in industrial markets. For sales managers, value-based selling requires two conditions: ability and motivation. The ability to sell value depends on the ability to conceptualize value in a way that resonates with customers, on processes encouraging a focus on value, on the availability of value-selling tools, on initial training, and on ongoing experience in value selling. The motivation to sell value is a function of salesforce compensation, of the ability to build long-term collaborative relationships with customers where both parties are committed to creating mutually beneficial value, of a company culture led by a strong CEO committed to value-based selling and, finally, of customers that recognize the opportunity to work collaboratively with suppliers. This chapter thus takes a nuanced view of the multiple facets that companies can and should control in order to implement value-based selling and value quantification. Todd also discusses a new term, total profit added, as a measurement for both buyer and seller to quantify total customer benefits. This approach considers not just cost reductions, but also includes estimated revenue improvements.

In the chapter “An inside-look at value quantification of competitive advantages” Evandro Pollono presents best-practice case studies on quantified value propositions. This is an important chapter. Many apparent experts advocate the importance of selling value, as opposed to selling price, without actually specifying in detail the data, the steps and examples of quantified value propositions. Evandro Pollono presents four examples of quantified value propositions, i.e. quantified, monetary customer benefits, calculated relative to the customer’s best available alternative, from B2B products as well as B2B services. These case studies convincingly show that value quantification is (a) possible and (b) beneficial in industrial markets, regardless of the intensity of competition or the perceived difficulty to differentiate the product.

In “Value quantification for services” Todd Snelgrove expands on the prior chapter and presents an example of a value calculator for services. Some managers are reluctant to quantify customer value for services, possibly assuming that value quantification for intangibles is more difficult or less credible than value quantification for products. This assumption is wrong: all products are, in the end, services (Vargo & Lusch, 2004). A product has a performance promise, like a service. A product customer co-creates value, like a service customer. Value is future-oriented, for a product as well as a service. Finally, some products are intangible (e.g. digital goods such as e-books), which means that the distinction between products and services is increasingly irrelevant. The subsequent chapter further expands on these issues.

In “Quantifying intangible benefits” Paolo De Angeli and Evandro Pollono make the point that intangibles – e.g. the value of a brand, sustainability – are an increasingly important competitive differentiator also in industrial markets. Key is to make intangibles tangible by specifying how intangible competitive advantages affect key customer business metrics, such as quality, revenues or cost. This chapter provides a case study on how to quantify intangible elements with a value quantification tool.

In “Towards a shared understanding of value in B2B exchange: Discovering, selecting, quantifying, and sharing value” Pekka Töytäri and Risto Rajala highlight the importance of conceptualizing value in a way that is shared between suppliers and customers. The authors present a three-step process enabling companies to quantify value: customer insight, value proposition, and value sharing. Value quantification is an iterative process. This chapter also succinctly highlights obstacles that companies face in the process of quantifying value: different assessments of the supplier’s value creation potential, inability to quantify value, and inability to defend value vis-à-vis procurement. Procurement is an obstacle for many companies aiming to implement value-based selling and value quantification. Industrial marketing and sales managers thus need to understand and influence the procurement function in order to credibly present value. The procurement function is the topic of the subsequent section.

“Part IV—Buying on value: Value quantification and B2B purchasing” contains several chapters that explore value quantification from the perspective of procurement. This is, as outlined, a unique feature of this book. Sales and account managers frequently perceive procurement as interested in price and price alone and are thus reluctant to adopt the mindset of an explorer that is fundamentally necessary in order to quantify value.

The chapters in this section convincingly debunk the idea that procurement is mainly and solely interest in price: sales is transitioning from price to value, and so is procurement. The fundamental idea is that the procurement function should not evaluate suppliers based only on quality, price, and delivery, but should instead evaluate suppliers based on their overall contribution to improved customer profitability.

Total value contribution (TVC) is the name for a metric that attempts to calculate the value that suppliers create for customers, value that is substantially broader than price or total cost of ownership (TCO). The chapter “Value first, cost later: Total Value Contribution as a new approach to sourcing decisions” by John Gray, Susan Helper, and Beverly Osborn develop the idea in detail. The TVC name by itself promotes attention to value. TVC’s structured approach begins with the question: “what do our customers, current and future, value about our products?” The TVC approach builds on insights from the literature on individual and group decision‐making to offset human biases and organizational incentives that emphasize cost reduction. TVC expands upon on the concept of total cost of ownership (TCO) which considers lifecycle costs, not just purchase price, but still is able to capture only cost-related elements. Total value contribution, by contrast, attempts to include also benefits and supplier contributions to improved profits, innovation or even sustainability. We are at the beginning of a process. Price and TCO are well established as supplier selection criteria, but fall short of considering strategic benefits. Total value contribution of procurement is thus a mirror concept of quantified customer benefits of sales. The concept of total value contribution needs to be more precisely defined – with a clear specification of categories – and it needs to be further researched – with studies documenting the link, and boundary conditions, of sourcing based on value, as opposed to sourcing based on costs, on innovation and profitability. To be clear: these studies exist, abundantly, for sales, but these studies do not yet exist for procurement. This is thus a very fertile ground for future quantitative, cross-sectional research.

In the interview “Selling value to purchasing,” Todd Snelgrove and Bo-Inge Stensson discuss how to implement value quantification vis-à-vis powerful industrial procurement departments. Contrary to the commonly held assumptions mentioned before, the authors also find that procurement is frequently willing to purchase based on value if—and only if—sellers are able to present a business case highlighting how a higher initial purchase price lowers costs or otherwise yields incremental financial benefits. This interview also highlights that within SKF the procurement function has undergone a substantial change. While in the past, annual price reductions and generic indicators of supply chain performance were primary performance measures, today the procurement function is increasingly measured by indicators relating supply chain performance to the company’s overall profitability and to the company’s overall strategic objectives such as innovation and sustainability. This change is demanding: both for the company itself and for suppliers who must conceptualize how their performance affects the performance of their immediate customers vis-à-vis their own customers.

In “Using best value to get the best bottom line,” Kate Vitasek contrasts three approaches that suppliers use to select vendors: price, total cost of ownership, and best value. This chapter is valuable: understanding alternative supplier-selection methods may enable buyers and sellers in industrial markets to change them. Price-based selection criteria consider either short-term or long-term purchase price. Total cost of ownership calculations consider supplier direct costs, supplier indirect costs, and a premium/discount reflecting the supplier’s risk. This approach, however, has drawbacks (Piscopo, Johnston, and Bellenger 2008; Snelgrove 2012). Total cost of ownership calculations do not consider the value of tangible (revenue improvements) or intangible (brand value, reputation, competencies) benefits. Total value of ownership (Snelgrove 2012), total profit added calculations (Snelgrove 2016), and value quantification tools (Pollono, chapter 9 of this volume) allow the inclusion of both tangible and intangible benefits, cost and benefits that make the customer better off. This chapter shows how to perform best value calculations. Best value is defined as the optimum benefits as defined by customers minus total supplier costs. Optimum benefits include, of course, intangible factors, too, such as reputation and quality. Selection based on best value is increasingly common in federal government procurement contracts. The chapter concludes by examining pricing models that align supplier and buyer interests; among these pricing models are performance-based agreements and vested agreements. The difference between these two approaches is fundamental: performance-based agreements consider key performance indicators; vested agreements consider the ultimate outcomes that truly matter to customers.

In “Value selling: The crucial importance of access to decision makers from the procurement perspective,” Rob Maguire describes the organizational buying process in the following terms: getting the least worst answer to the wrong question from people you’ve met online. A key task that sellers face is, first of all, to understand what buyers want: price, a benefit, or a solution, in the authors’ terms. Second, if sellers want to implement value-based selling and value quantification, they need buyers that recognize the need to purchase a solution—as opposed to purchasing an item at the lowest price. Once buyers recognize the opportunity or need to purchase solutions, sellers should practice the following steps: investigate value creation opportunities, quantify the incremental value delivered, engage buyers in mutual value creation opportunities, sell value and, finally, implement value-based pricing via, for example, outcome-based contracting. This chapter is thus a reminder that access to the ultimate decision maker, and not necessarily access to procurement, is a necessary prerequisite to implementing value-based selling and pricing.

In “The sourcing continuum to achieve collaboration and value,” Kate Vitasek examines alternative configurations of buyer–seller relationships. Transactional, market-based models include basic or approved provider models. Relational models, that is, hybrids between markets and hierarchies, include preferred provider relationships, performance-based contracting, and vested business models. The author discusses the latter two models in detail in chapter 10. Equity, investment-based models include shared service models and equity partnerships. This chapter describes these alternative configurations in detail and offers guidelines that facilitate the selection of the most appropriate model in buyer–seller relationships.

“Part V—Value quantification and organizational change management” contains two interviews with senior B2B marketing and account managers.

In this section’s first interview, “Implementing value quantification in B2B,” Matthias Heutger and Andreas Hinterhuber discuss value quantification for industrial services. Value quantification is, according to Heutger, always beneficial, even if organizations are strongly driven by the procurement function. In other words: even if suppliers do not require customers to quantify their value, suppliers should still do so in order to differentiate themselves from their competition. Heutger makes one point clear: value quantification requires that suppliers understand their customers’ entire supply chains, end-to-end. Suppliers must be able to understand the effects of their own incremental performance improvements on the performance improvements of their customers’ customers. This understanding also enables gainsharing agreements—with a caveat: gainsharing agreements require a long-term collaboration whereby both parties are committed to innovate and change. The interview also explores the antecedents of value quantification capabilities at the level of the individual sales and account manager: a strong customer focus, the ability to strategize, listening skills, and a willingness to experiment. Another important aspect of value quantification is credibility: the ability to actually deliver on the promised value may require selecting those persons within the customer’s business who most appreciate the value created; it frequently entails small tests which are then rapidly scaled up. Value quantification is, in Heutger’s words, a true organizational transformation that requires senior management commitment, structural changes, and changes in hiring profiles. Where to start? At the level of the individual customer. Value quantification requires a new way of interacting with customers where “trust, mutual benefits and a willingness to grow together over time” take the place of price as the main element of discussion. These words will, we hope, withstand the test of time.

In the second interview of this section, “The ring of truth—Value quantification in B2B services,” Pascal Kemps and Andreas Hinterhuber discusses value quantification in complex B2B services. To start off: the importance of value quantification seems to grow with the importance of customers, to a point where it is factually required by strategic accounts. Second, and more counterintuitively, Kemps suggests: The fact that some customers treat suppliers transactionally does not imply that suppliers should not treat these customers strategically. Transactional customers—customers who bid out every contract—may enable suppliers to standardize their own internal processes or to accumulate valuable competencies and insights. Treating them transactionally or, worse, writing them off would mean, according to Kemps, cutting off profitable business. Next and again controversially: collaborative customer relationships where suppliers quantify value beyond price may yield process improvements that could mean that suppliers end up selling less. This ability to solve customer problems even at the expense of the supplier’s own, immediate and certain sales forges customer relationships which are, truly, strategic. Next: Kemps warns against the folly of managing by key performance indicators (KPIs). KPIs are typically related to business processes which have only a random fit with the few business outcomes customers ultimately want to achieve: improvements in profitability, customer satisfaction, or innovation, for example. Kemps suggests that the cultural alignment between traits of customers and traits of the account management team is the most important factor enabling value quantification and effective collaboration. So where should companies start that wish to become fully proficient in value quantification? Kemps offers two pieces of advice: Number one: patience and perseverance—once the direction is clear, perseverance is required. Number two: the relentless pursuit of differentiation—the opportunities for joint value creation—is limited only by individual imagination. Finally: the ring of truth—value is a promise; results are all that matter to customers. Kemps suggests that presenting the value credibly in ways that customers can relate to and verify for themselves is fundamentally important in the context of value quantification. Companies that excel at quantifying value cut through the fog of vague data and promises. The ring of truth is thus the metaphor for the ability to summarize the fruits of much thought and labor briefly and clearly.

“Part VI—Buying and selling on value: Value quantification tools” presents three chapters discussing value quantification tools.

In “A question of value: Customer value mapping versus economic value modeling,” Thomas Nagle and Gerald Smith make a strong case against customer value mapping in the context of value quantification: Only a detailed step-by-step analysis aimed at quantifying the quantitative and qualitative benefits of a differentiated product can provide insights into total customer value and maximum willingness to pay. Simply put, customer value mapping assumes (a) that customer willingness to pay is proportional to the benefits provided, and (b) that customers weigh benefits and prices equally. Both assumptions are wrong. Only a detailed mapping of the subjective, customer-specific economic benefits of a product—conducted via economic value measurement (Nagle and Holden 2002), value calculators (Hinterhuber 2015), or value word equations (Anderson, Narus, and Van Rossum 2006)—yields insights into customer maximum willingness to pay. The widespread diffusion of customer value mapping is no indicator of its scientific value: bad practice, unfortunately, can persist for decades and centuries. This article makes a strong case for a scientifically robust (Sinha and DeSarbo 1998) approach to quantifying value and price in B2B and B2C markets.

In “Why start-ups should consider using value propositions,” Lennart Foos and Markus Kirchberger make a case for value quantification via the customer value proposition also for start-ups. In this chapter, the authors provide a step-by-step guide to developing a monetary customer value proposition. The research underpinning their work suggests that the early development of these value propositions increases the chances of selecting appropriate target markets and of successfully introducing new technologies. The development of quantified customer value propositions is thus a capability that aspiring entrepreneurs must master.

Tim Underhill, in “Creating and sustaining competitive advantage through documented total cost savings,” likewise suggests that quantifying customer benefits is necessary and beneficial for suppliers. This chapter provides a case study of value quantification in industrial markets.

“Part VII—Epilogue” contains several short chapters that summarize salient aspects of value quantification and provide an outlook on the shape of value quantification capabilities in the future.

In “A call to action: Value quantification in B2B buying and selling” Todd Snelgrove invites both B2B procurement and B2B sales managers to quantify value in industrial buying and selling in order to uncover opportunities for mutual value co-creation in B2B exchange relationships.

In “Quotes and Statistics to Help you on Your Value Selling Journey” Todd Snelgrove presents quotes and summary statistics that attempt to highlight why value quantification is beneficial, both for sales, as well as for procurement.

The final interview “The present and future of value quantification” by Andreas Hinterhuber and Todd Snelgrove sheds light on future capabilities related to value quantification. As outlined by several authors in the present book, value quantification in the future will focus on quantifying intangibles, including the quantification of non-economic benefits—likely even factors such as the value of a lower environmental impact. Value quantification capabilities are, and will be, a key differentiator between high- and low-performing companies. In the future, value quantification will be employed throughout the sales cycle, with an increased focus on it in the new product development phase and an increased focus on innovative pricing models and performance-based and value-based pricing models. Finally, if value quantification is a recursive, iterative process, the availability of big data and experience will enable managers to make predictive assessments of customer-quantified benefits based on both human and artificial intelligence.

Sales and marketing are transitioning from price to value. We understand the idea of value and its multidimensional nature. In the context of quantifying value from the perspective of sellers, value is equal to the sum of quantified, monetary customer benefits, i.e. the sum of quantitative customer benefits—revenue/gross margin increases, cost reductions, risk reductions, and capital expense savings—and qualitative customer benefits—such as ease of doing business, customer relationships, industry experience, brand value, emotional benefits or other process benefits—expressed as one figure equating total customer benefits received (Hinterhuber, 2017). We know what value quantification capabilities are and we know, via numerous, independent, converging studies, that value quantification capabilities increase firm performance. This is the perspective of sales and marketing. Here, academia is clear and ahead of practice: the research, the examples and best practices presented in this book can help companies still selling based on price or features to transition to selling based on value. Academic research is very clear: this will improve company performance.

Procurement is also transitioning from price to value. We do have an initial understanding that traditional metrics, such as price or total cost of ownership, are unable to capture the full spectrum of benefits that suppliers bring to customers. We also have an initial idea of a metric able to quantify tangible and intangible supplier benefits – total value contribution, discussed in this book, is one example of such metric.

Ideally, the metric that sales managers use to sell value to procurement – quantified, monetary customer benefits (Hinterhuber, 2017) – is the same metric that procurement uses to evaluate alternative offers from sales managers. The further development of a metric able to capture all tangible and intangible benefits of alternative offers in sourcing decisions will thus, in the end, build on the value quantification and pricing literature that has already produced them.

This is extraordinary and fantastic.

This is spectacular since the development of all – well: at least a good part – of what we know in strategic pricing – the idea of customer value as sum of reference value and differentiation value (Nagle & Holden, 2002) – i.e. the big bang of strategic pricing, originated from research in procurement – value engineering – in the 1950s aimed at calculating maximum purchase prices. This is the lasting contribution of Tom Nagle, who almost single handedly created the field of strategic pricing as we know it.

This spectacular journey started in procurement, it inspired the nascent literature on strategic pricing which now, in late adolescence, inspires the mature literature on procurement in developing strategic sourcing models. Procurement, pricing, procurement – this is the beautiful journey, based on a very simple idea. Value first, then price.

References

Anderson, J. C., Kumar, N. and Narus, J. A. (2007) Value Merchants: Demonstrating and Documenting Superior Value in Business Markets, Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Anderson, J. C., Narus, J. A. and van Rossum, W. (2006) “Customer value propositions in business markets,” Harvard Business Review 84(3), 90–99.

Heath, C., and Heath, D. (2010) Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard, New York: Random House.

Hinterhuber, A. (2015) “Value quantification—The next challenge for B2B selling.” In A. Hinterhuber and S. Liozu (Eds.), Pricing and the Sales Force (pp. 20–32), New York: Routledge.

Hinterhuber, A., & Liozu, S. (Eds.). (2020). Pricing Strategy Implementation:Translating Pricing Strategy into Results. Routledge.

Keller, S. and Price, C. (2011) Beyond Performance: How Great Organizations Build Ultimate Competitive Advantage, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Kellogg, K. C. (2008) Not Faking It: Making Real Change in Response to Regulation at Two Surgical Teaching Hospitals, Working Paper, MIT Sloan School of Management.

Kotter, J. P. (1995) “Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail,” Harvard Business Review 73(2), 59–67.

Nagle, T. T. and Holden, R. K. (2002) The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing: A Guide to Profitable Decision Making (3rd ed.), Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Piscopo, G., Johnston, W. and Bellenger, D. (2008) “Total cost of ownership and customer value in business markets,” Advances in Business Marketing and Purchasing 14, 205–220.

Sinha, I. and DeSarbo, W. S. (1998) “An integrated approach toward the spatial modeling of perceived customer value,” Journal of Marketing Research 35(5), 236–249.

Snelgrove, T. (2012) “Value pricing when you understand your customers: Total cost of ownership—past, present and future,” Journal of Revenue & Pricing Management 11(1), 76–80.

Snelgrove, T (2016) “Value First the Price – Quantifying Value in Business to Business Markets from the perspective of Both Buyers and Sellers” Routledge 2016

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004) “Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing,” Journal of Marketing 68(1), 1-17.

Töytäri, P. and Rajala, R. (2015) “Value-based selling: An organizational capability perspective,” Industrial Marketing Management 45, 101–112.